Christopherson: Instagram Is Finally Starting to Matter

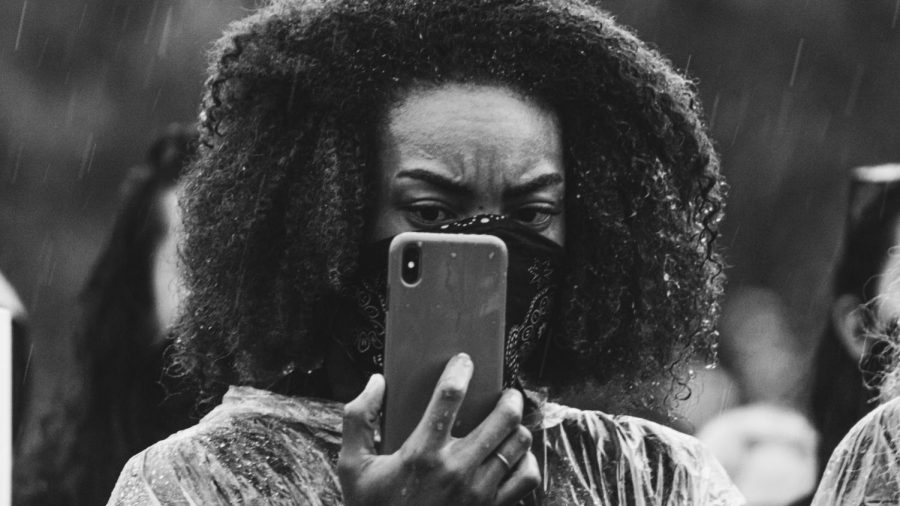

An attendee to Equality Utah’s ‘Pride for Black Lives Matter’ event records the crowd and speakers gathered at Liberty Park in Salt Lake City on June 14th 2020. (Photo by Mark Draper | The Daily Utah Chronicle)

July 5, 2020

Did you see the sky on the evening of June 4? It was exquisite — only believable because we live in a valley of perpetually pink sunsets. The moon seemed all the more vast for the pale blue lingering past 9:00. The clouds were quietly radiant against Salt Lake City’s bright green urban forest.

A week or two before, I would’ve taken a picture, and probably put it on my Instagram story. But the social media platform has undergone a rapid coming of age over the last few weeks, and most college kids aren’t really using it for sunset pics now. Or selfies, or vacation photos, or occasion-less portraits with significant others — none of the kinds of validation-seeking images we’ve all been posting for the last ten years.

Instead, since George Floyd’s murder at the hands of a white police officer on May 25, young adults are using Instagram to share knowledge and information. What do you know about the project of whiteness? What have you learned about police brutality in Utah and across the U.S.? We’re using it to share resources. Here’s what you can do to be an ally to the Black community, and here’s what you can do as a University of Utah student. Here’s how to demand justice for Breonna Taylor. Here’s how to respond to common racist remarks. We’re using it, at long last, to express our support for a movement that has been raging for years, while many of us — read: many white people — turned a blind eye.

Most glaringly, we’re using Instagram to judge each other on a totally new level. We’re demanding that judgment. When I scroll through your profile, it’s no longer to see whether you’re dating anyone or how pretty you are. It’s not to get a sense of your interests or your popularity. I’m looking to see whether you’re anti-racist or not.

There are a handful of key indicators. You might’ve posted a black square on June 2 — but did you use #BlackLivesMatter or #BlackoutTuesday? If you reposted content to your story, was it a non-specific message about the beauty of diversity or helpful information about what to do? Were you sharing only white people’s views and experiences or amplifying Black voices? Maybe you’ve posted photos from a protest you attended, but did you take care to protect others from police retaliation by blurring their faces? Are you back to sharing carefully curated images of your life, or have you stayed focused on the 401-year-old crisis at hand?

We need a way to assess our peers’ and loved ones’ commitment to anti-racism — not to mention commitment from brands and organizations — so we can educate those who are well-meaning but ignorant and, when necessary, end relationships with racist people. In that way, Instagram is playing a second essential role in the movement for Black lives, in addition to being a kind of crowdsourced guide for how to participate. That said, it’s dangerous for social media to be the only — or at least the easiest and likely the most popular — mechanism for that kind of high-stakes judgement, since everything we do on Instagram is performative on some level.

On the one hand, many of us avoid using social media for various reasons. Some people are simply uninterested; others, like myself, are prone to falling down rabbit holes and checking our notifications with unhealthy frequency, so we find it easier not to log on in the first place. Is it fair to judge those people as racist — or, at best, unengaged in this movement — because they aren’t adding lists of Black-owned local businesses to their Instagram story every day?

On the other hand, it’s perilously easy to give into slacktivism, simply re-sharing content by other people in an effort to convince our followers we’re invested in social change. The fact that someone looks engaged from a virtual perspective does not mean they are doing the uncomfortable, sacrificial, necessary work of donating to pro-Black groups, contacting their local leaders, examining their own racial bias or seeking out and listening to Black voices. Even as activists are beginning to call for non-optical allyship — these private anti-racist behaviors that truly help to dismantle oppressive systems — Instagram remains the most accessible tool for us to evaluate our friends’ integrity; their willingness to call attention to the realities of racism and police brutality in the United States instead of their own happiness and beauty and success, and even their own problems.

That might be the bottom line, in fact. On the most basic level, Instagram is about what we care to draw attention to. It’s about how each of us uses our platforms and our skills as digital natives rather than what everyone else is or isn’t doing. So, knowing that the fight to end racism and police brutality is nowhere close to over, and knowing that it must be sustained in order to succeed, can we ever totally go back to the way things were?

I don’t think so.

For some of us, that may mean returning to an often toxic and anxiety-inducing platform to let our followers know where we stand and ask them to take anti-racist action. Others of us should keep in mind that to slip back into our old posting behaviors — to deliberately pull our followers’ focus away from this urgent movement — would be insensitive at best. At worst, it would smack of a kind of Trumpian sentiment, implying the need to make Instagram great again when it wasn’t always good in the first place.

Or it would be an acknowledgment that rest from the emotional labor of thinking about and confronting racism, while a privilege, is crucial to our well-being and the movement’s? Or a recognition that the real work of change doesn’t happen on Instagram, and the things we post don’t matter so much?

In other words, the choices we make about what to share on Instagram are as personal now as they have always been. Just a lot more complex.

The good news is that despite this messy and painful coming of age — for us and for Instagram — the famous middle school assembly mantra still holds true: “T.H.I.N.K. before you post.” Be timely. Be helpful and inspiring. Share only what is necessary in this moment and only what is kind — because, like the world, Instagram is what we make it.