January 24, 2022

Thirty-five works by Japanese American artist Chiura Obata are set to join the Utah Museum of Fine Art’s permanent collection in Fall 2022.

“Building a collection for future generations of humans who will call Utah home is really one of the most exciting and most important things that we do at a collecting institution like the UMFA,” said UMFA Executive Director Gretchen Dietrich. “To bring the work of Chiura Obata into this collection is a really exciting thing for us. Adding his work to our collection is going to serve the museum well.”

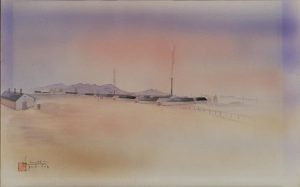

Much of Obata’s work is inspired by the World War II internment camps, which held many Japanese American citizens, beginning in 1942 and ending in 1946. Obata and his family were among the Japanese Americans who were wrongly incarcerated. Specifically, they were held in the Topaz Internment Camp in Delta, Utah.

The UMFA first connected with the Obata family through a traveling exhibit dedicated to Obata’s work. The exhibit was displayed in many museums, including the UMFA.

According to Obata’s granddaughter, Kimi Hill, she and her family immediately thought the UMFA was a perfect place for the exhibit to make a stop.

“Topaz Museum is located two hours away,” Hill said. “It would be perfect if people could see the Obata art and maybe, hopefully, be inspired to go visit. It’s so important [that] if people are even just a little bit curious about this part of American history, they go to the actual site.”

She described herself as the Obata “family historian” and says that discussing her grandfather and educating others on his life brings her closer to him.

“At this time in my life, I feel like I am in a really good relationship with my grandfather,” she said. “That’s a funny way to say it, but we seem to be hanging out a lot because of all the interest [in his life].”

Hill said that despite Obata being the only real expert on himself and his life, she does her best to interpret his story and has learned a lot from it.

“I really appreciate his philosophy and his tenacity to live the way he wanted to and with his values,” she said. “It’s a nice way to be guided at this time in my life.”

According to Hill, people seem to find Obata through his art and stay to learn his story.

He was born in 1885 and grew up in Sendai, Japan, where he was raised by an older brother.

Hill said Obata loved to draw and paint from a young age and was trained in the sumi style of painting.

When Obata was 14, he ran away to Tokyo, Japan, where he found a master painter to work under as an apprentice. In Tokyo, Hill said, Obata was heavily influenced by the West.

“It was very cosmopolitan,” Hill said. “The West was interesting. [As] an artist, he wanted to go to the art capital of the world, Paris.”

At this point in his life, Obata was beginning his career as an artist.

“He was adventurous and restless,” Hill said. “He wanted to travel and support his artistic interest.”

Hill said Obata’s adventurous nature is what brought him to the United States.

“He was curious,” she said. “He thought he would come to California, at first, to make money and then keep going. But what happened is he really fell in love with California, and grew friendships and married.”

Obata settled in San Francisco, and was present during the 1906 San Francisco earthquake.

“He came from Japan, which has earthquakes all the time,” Hill said. “He didn’t panic. He got out of his room in one piece and then, immediately, because he’s an artist, started sketching. He has small sketches that are depictions of the aftermath of the earthquake that are in the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco.”

Hill attributes this to Obata’s optimistic attitude, an attitude that would follow him into the Topaz Internment Camp.

“The first day of the forced removal, he’s thinking of starting an art school,” Hill said. “It started at the first camp, which was a detention center while they were building Topaz.”

Hill described that, within a month, Obata and his family began an art school.

“They had no money from the government,” she said. “The government, basically, gave them a building to use and that was it.”

The art school was very successful, drawing children and adults alike to its classes.

“One of the best stories is that they were able to have an art show,” Hill said. “They were trying to keep a hold of some resemblance of normalcy and, you know, a life instead of being thrown into this completely unnatural situation.”

One of Obata’s primary messages is to learn from nature.

“He described it as ‘immerse yourself in nature, listen to what nature has to tell you,’” Hill said. “I think ultimately that was it. We’re living beings within a natural world, if we don’t have a close relationship with that and grow together or help each other, then it’s going to go sideways.”

Dietrich said there is no doubt in her mind that Obata is a very important American artist.

“I think he was thought of primarily, for a long time, as a Japanese American artist and, you know, pushed aside a little bit for not great reasons,” Dietrich said. “The truth is, he lived and worked as an artist in the United States. He was trained [in] and good at traditional forms of Japanese art. He took traditional forms of making art in the Japanese way and made American art. [Obata] showed us American landscapes and American people in really important, interesting and incredibly beautiful ways.”

Dietrich believes Obata’s works to be beautiful, powerful and connected to both historical and contemporary issues.

“They connect us to contemporary issues, [like] when we think about the immigrants at the Mexican border, and the ways in which we’re sort of keeping people in detention centers until we can sort out their coming into the United States,” she said. “Those are complex and very painful issues that aren’t really new. They are relevant and present in [Obata’s] work, and I think that’s what great art is all about: It offers new ways of thinking about and thinking through challenges that we are facing.”

The Utah Museum of Fine Art’s (UMFA) pivotal acquisition of 35 artworks from renowned twentieth-century, Japanese-American artist Chiura Obata will bring critical artworks that explore the complexity of American history and identity to our own backyard on the University of Utah campus.

“We wanted to represent the breadth of his work,” said UMFA’s Senior Curator Whitney Tassie. Obata’s career was an astounding seven decades long and he produced a vast array of works including Sumi ink drawings, magazine cover illustrations and woodblock prints. He is notable for skillfully translating vast landscapes onto paper by accenting dark outlines and curves in captivating colorscapes. His manner is straightforward, yet makes the viewer feel minute in scale as if they were stepping into his images. I am personally left astounded by Obata’s continual ability to fit grand expanses into single frames.

“We just looked through his career at themes that he kept returning to and themes that resonated particularly with our collection,” Tassie said. Obata’s style utilizes Eastern art practices while depicting the West, showing underrepresented yet needed views within American art history. “There are a lot more voices and a variety of creative practices out there that contributed to the progression of art in our country,” said Tassie, who shared her excitement in finding works that include quintessential elements of the American west, such as horses. “This figure of the horse seen through these different perspectives … That was something we were really excited to get.”

Having Obata’s work in Utah is a special privilege, and the collection’s bestowment has been in the works since 2017. A majority of the collection was gifted to the UMFA by the Obata family, who wish for the collection to inspire viewers to study their history — Obata had been incarcerated in the Topaz Internment Camp during World War II. “We didn’t only acquire his work from his time when he was at Topaz — it was before and after because he had such a strong oeuvre. It would be essentializing and misleading to only have the work he created while he was interned,” Tassie said.

Focusing solely on Obata’s internment limits the impact of his artwork as a whole, yet simultaneously, the works he produced in internment are imperative as they document the incarceration of Japanese-Americans. “If you are going to talk about regional art history … [Topaz] absolutely must be part of it, and beyond that, it’s part of American history,” Tassie said. “The issues that he was talking about, anti-Asian sentiment and oppression from the American government, are still very timely and relevant today.”

Careful examination and preservation efforts are required for the medium and nature of Obata’s works, meaning exposure time must be limited. “They are mostly in good shape, but some might need treatment,” Tassie said. “They’re all works on paper which means they are light-sensitive.” The UMFA has not released an official date for the collection’s release into the American galleries, but viewers are glad to wait for the work’s necessary processing. “It’s not something we want to rush into,” Tassie said.

Overall, welcoming the Obata collection to the UMFA is an incredible opportunity. “There are so many voices and complexities that exist that aren’t always expressed in the canonical narratives you hear over and over again,” Tassie said. “This idea of a multivocal narrative is something I’m hoping people will take away. That’s the hope and why it’s important to have his work and to share it.”

Obata was a teacher and will always be a teacher, and now Utahns have the opportunity to experience the potent impact of Obata’s works permanently on UMFA walls.