Flint, Mich. is a town where 40 percent of the people live below the poverty line, 73 percent of the population is not white and the residents have been drinking toxic water for the past year because of poor decisions made by their government and elected officials. Lead poisoning of the people of Flint is a gross example of the environmental racism that exists in our country and a case study in why state-led environmental standards of protection are not enough.

Flint used to be a typical, blue-collar working-class town, until the auto-industry collapsed in the ‘80s and ‘90s. The once-industrious town turned into an impoverished, depopulated skeleton of its former self. In Flint, there are no grocery stores, 15 percent of the homes are boarded up, and according to Business Insider, it’s rated as one of “the most dangerous cities in America.”

Because of these statistics, Flint has become a forgotten destination for business ventures and politics, and the city has fallen into stereotypical socio-economic statistics of crime and poverty. The financial situation in Flint was so bad that in 2011 the city was declared to be in a state of “Financial Emergency,” and the governor appointed a financial manager to handle the crisis. Ultimately, elected officials decided to switch Flint’s water supply from Lake Huron, for which they were paying Detroit, to the Flint River, which local residents described as being notoriously “filthy,” in order to save money. Unfortunately, because Flint was in a vulnerable position, the government recognized and took advantage of the people’s lack of political or organizational power, leading to a race- and class-based environmental justice issue.

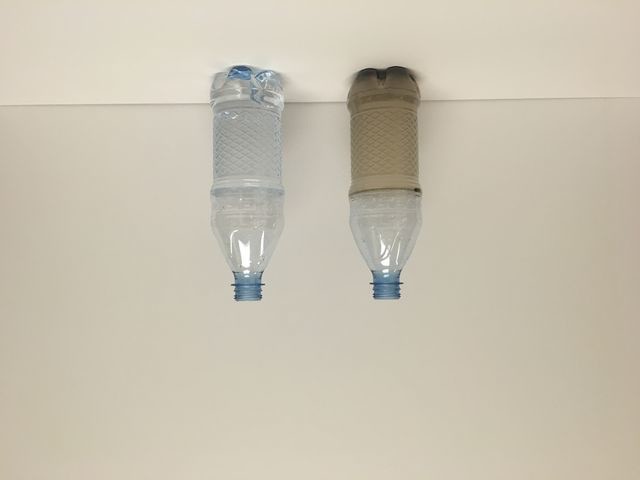

Even when residents questioned the brown, dirty-tasting water coming from their taps, their voices were quelled by city officials reassuring them the water was safe. But pediatric doctor Mona Hanna-Attisha refused to accept these false promises when she saw the skin lesions, hair loss and rashes (symptoms consistent with lead poisoning) on her child patients. Eventually, corroborating evidence supporting Hanna-Attisha’s testimony was further provided by Virginia Tech students studying lead levels in the water. By this time, there was no disputing it. The water, which had been deemed “safe” many times by government officials, had 10 times the levels of lead previously reported by the state.

The Michigan State Department of Environmental Quality and Governor Rick Snyder blatantly ignored federal regulations and put Flint citizens at risk. The worst part is that the situation could have been avoided. An anti-corrosive agent could have been added to the water for a mere $100 per day, which would have prevented 90 percent of the problems, but the state refused to shell out the money.

Abhorrent situations like the one in Flint remind us why we need federal oversight of environmental issues. Michigan is a conservative state, and their resistance to federal environmental standards largely contributed to the failure of the state’s Department of Environmental Quality to protect the people and responsibly manage the natural resources of Flint. It is sad that the children who were affected have a higher probability of developing behavioral problems, lower IQs, poor grades, problems with hearing, learning difficulties and growth delays because of the gross negligence and racism of Michigan’s government.