The situation has little nuance: on a beach in Santa Teresita, Argentina, a herd of tourists pulled a few rare adolescent dolphins from the ocean and caused the negligent death of at least one. Once the camera-laden crowd finished what it set out to do — obtain the perfect dolphin selfie — the marine mammal’s corpse was left on the sand to bake in the Argentinian sun. Hernan Coria, a tourist at Santa Teresita taking pictures that day, said the dolphin had already died before being passed around for pictures — a claim immediately contradicted by footage showing the live dolphin moments before it was pulled from the water. Live or not, the fact that pictures both caused and captured this sinister event is deeply troubling.

My ire is easier explained if I allude to a scene in White Noise by Don DeLillo. In the novel, two characters drive to a spot known as the “Most Photographed Barn in America.” There, they ruminate on the fact that every person taking photos of the barn can’t really see it. Instead, they (the tourists) see only the attraction of the title, blind to the structure’s otherwise ordinary barn-ness. At one point, a character says of the experience, “We’ve agreed to be part of a collective perception. It literally colors our vision. A religious experience in a way, like all tourism.”

This may seem trite, as though a scene simpler or more natural than the tourist destination photo spot could hardly be imagined. Despite this, I believe strongly that there’s a great deal of humanity lost in the collaboration between the ego and the photograph — one that manifests itself completely in the selfie. If you aim to photograph the most photographed barn, you do this neither to promote the integrity of the barn or to really enjoy being at the barn at all. You do this to show someone that you’ve been to the most photographed barn. The long-winded point being, you become a capital-T Tourist when you focus not on appreciating a thing’s existence but on how its existence can be beneficial to you. This is true to a painful degree in social media-driven tourism.

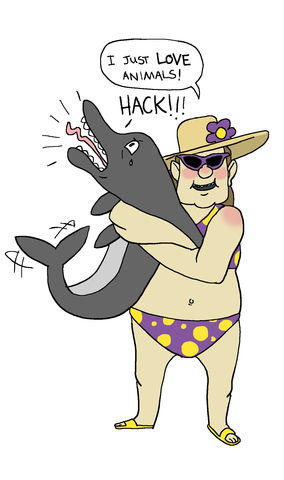

I think the situation becomes even more eye-opening, however, when regarded in the context of the selfie. By no means is there a lack of literature on the perils of selfie taking. People die every year reaching for the coolest, riskiest place to capture a photo of themselves. I, perhaps unfairly, consider the serial selfie little more than an ego trip fueled by the Internet and social media. As more people find it compelling to attain a degree of popularity and intrigue online, the cult of the ego rises in direct and immediate proportion. People get the idea to take a photo with a dolphin they’ve found swimming in shallow water, and suddenly the dolphin exists no longer as dolphin (cf. barn, above), and the dolphin becomes a tool by which the people can achieve a modicum of the popularity so sought after by the ever-present, ever-nasty ego.

I could be bonkers. The incident in Santa Teresita might be little more than a textbook example of mob mentality run wild. My goal is not to completely bash the selfie as a genre of self-expression. I’m not trying to say that all social media is simply mediated masturbation. However, I think when we use outlets to make our personalities visible, we must be aware of the oft-ignored point at which we begin to sacrifice whatever humanity we possess for the chance to be well-regarded. What this becomes is a sort of Faustian tragedy at the level of Instagram and Snapchat. I don’t think it’s a healthy thing that our collective perception is so easily manipulated by a desire to seem likable or popular or well-traveled. I don’t think it’s good that, from a young and naïve age, humans are exposed to a relatively undeveloped online culture that is sometimes beautiful, though also extensively ugly and selfish and dumb.

This is also not to say that the dolphin in Santa Teresita was killed only by a collective act of pure ego. But the dolphin is dead, and the cause is pretty well-determined. I think instead of berating those who took part in this gang-murder, we should look to the motivation that made such a terrifying scene possible. It’s apparent that those who took part in the exercise did not see the dolphin for what it was. I’m hopeful that, given the same situation but without a crowd, the dolphin would have remained untouched or at the very least alive. But as it stands, we have one well-publicized instance of ego-mediated groupthink that is actually much more sinister and suggestive than I think surface-outrage is currently conveying. Like the most photographed barn, how can we expect to really see the object of our photographic attention when we immediately ignore the value of object itself. It’s a slippery slope of ignorance, one that first leads to the murder of a rare and innocent dolphin and then begs the question: what, or who, is next?