Our beliefs and values shape the way we look at the world and the way we treat it. Unfortunately, our paradigm of normal has exempted accountability for those who hold positions of power. When we give a person a badge and gun, we allow ourselves to be subjugated under the guise that we are offered safety and protection in return for our subordination. But this exchange has yielded up power that is not appropriately checked, and it left 17-year-old Abdi Mohammed critically injured after he was shot twice by police officers in downtown Salt Lake City on Friday, Feb. 27.

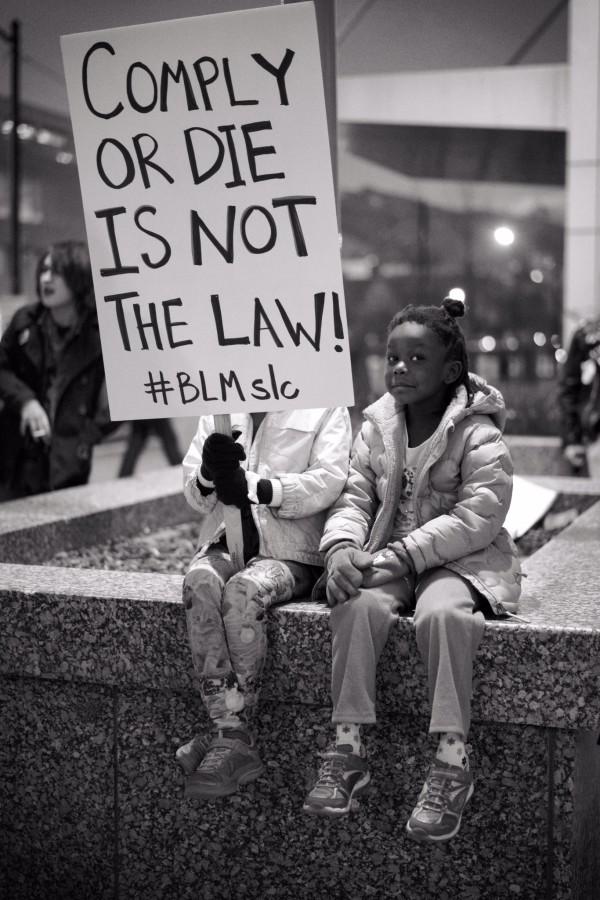

We are getting too used to this narrative: another unarmed, black teen was shot by police officers. Racism these days is tricky to pinpoint because it’s no longer an individual act of cruelty and prejudice. It exists within our institutions, and white privilege is too often unacknowledged. The Black Lives Matter movement and protests after officer-involved shootings are aimed at exposing this institutional racism, which only becomes visible in this extreme form of public upheaval. The protests go beyond incidents of black teens getting killed by police officers.

Even though most people do not identify as inherently racist, research in the fields of social psychology and neuroscience reveals that people who say they believe in equality and fairness still “show significant patterns of bias” according to David Amodio and other neuroscientists at New York State University. The amygdala, which is linked to fear responses inside the brain, show that a plurality of white people react fearfully to seeing pictures of black males.

Cognitive dissonance allows our psyche to justify the shootings and maintain the status quo. We often victim-blame and justify the acts rather than looking at the situation as a whole. In this event, we rationalize the shooting of a child because “Abdi did not put down the broomstick/pipe when officers instructed.” But officers are trained to de-escalate situations. The deeper we delve into the social and economic disadvantages Abdi faced, coupled with the sad but illuminating fact that black males are 21 times more likely to be shot by police than their white counterparts, we must face the situation for what it is. We must recognize and condemn this injustice before we can rectify it.

Part of what makes race so hard to talk about is that it poses serious challenges to the status-quo. Changes to racist structures in our urban environments as well as our natural environments would threaten the existence of its profiteers. We like to think that the outcomes of our life, including success or failure, are entirely dependent upon the life choices we make and the work we put in. Good choices generally lead to good things and bad choices will get you shot by police officers — or so the popular narrative goes. This flawed perspective leads people to assume their life achievements are wholly a consequence of the choices they made. We should recognize there are systems in place that are tipping the balance against the poor and against minorities.

A black male needs the equivalent of 10 years of experience to be considered as a candidate for the same job as a white person. A person with a “black”-sounding name receives 50 percent fewer callbacks than an equally qualified applicant with a “white”-sounding name when sending out job applications. A black male is three times more likely to be searched at a traffic stop. Blacks aren’t pulled over (and subsequently jailed) more frequently because they’re more prone to criminal behavior — they’re pulled over more frequently because there is an “implicit racial association of black Americans with dangerous or aggressive behavior,” according to the U.S. Innocence Project.

While this article is not aimed to vilify police or target police supporters, it is meant to waken our collective mind to the institutional racism that exists and to rectify this need for domination. It is also a warning to all of us who are, by virtue of our citizenship and membership in this society, subjected to the authority of people with effectively unfettered power.

Unchecked power can lead a good person down a very corrupt path. Remember the Stanford Prison Experiment, where psychologist Phillip Zimbardo was conducting psychological research as to what would happen when good people were put into an evil place? Half of the test subjects were treated as prisoners, and half of the volunteers were given unchecked authority and acted as guards. The prison became so dehumanizing and unethical that the experiment had to be cut short from two weeks to six days.

Power can corrupt, and the followers willing to collude and make such exceptions for poor behavior should also reevaluate their position. Our history of dominance over other people should have been stopped when we learned this lesson from our history books the first time. The perpetuating cycle of domination should not continue to be a part of our cultural story.

letters@chronicle.utah.edu