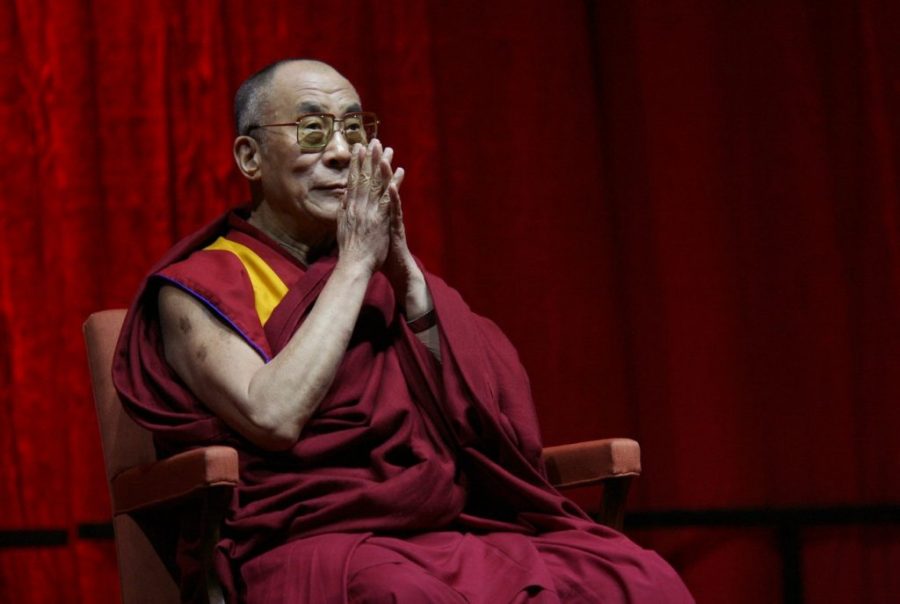

His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama of Tibet makes his visit to the U in the midst of a political and global climate pocked too regularly with ugly acts of violent extremist terrorism. In light of such horrific, morally arctic events, like the massacre at an Orlando LGBTQ club on June 12, it’s hard – at least for me – to be receptive to suggestions that espouse non-violent retaliation.

However, the wisdom of His Holiness gives me pause. “Violence inevitably incurs further violence,” he writes in an Op-ed for The Washington Post. To him, the way to beat hate and anger is not with harsh rhetoric but with love and compassion. The patience of this wisdom offers some respite in our age of seemingly unending turmoil. His reliance on compassion and his belief in the primacy of secular ethics over religious doctrine – including his own – set him apart as an example for all of us.

The man is not far separated from the myth. Tenzin Gyatso (the abbreviated form of His Holiness’ given name) became the temporal ruler of Tibet at the humble age of 15, studying in the monastery for nine years already. At 19, he was made a delegate to the National People’s Congress in China. At 23, he fled a China-operated Tibet and headed a new government in Northern India, leading nearly 80,000 of his fellow Tibetan refugees to religious sanctuary, thereafter severing ties with the People’s Republic of China. He was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1989, and in 2007 was given the Congressional Gold Medal by the United States. Now, for a man whose future reincarnation is heavily politicized and whose health is a matter of geopolitical concern, he’s a surprisingly active 80-year-old.

In speaking at the U.S. Institute of Peace on June 13, the Tibetan spiritual leader did what he does best: he made the case for non-violent conflict resolution. His message comes at a period in U.S. history when we are probably least likely to heed such a suggestion. In the hours following Orlando’s gun-driven tragedy, politicians and constituents alike defended gun ownership despite murderer Omar Mateen’s prescient use of the AR-15 – the same gun used in the massacres at Sandy Hook Elementary School, Umpqua Community College in Roseburg, Oregon, and in San Bernardino, California, late last year. Trump (who can reasonably be considered the anti-Lama) almost immediately pandered to the gun lobby, remarking that if more guns had been on the side of the good guys, “you wouldn’t have had [that] tragedy.” If more guns made the world a safer place, you’d think the U.S. would be one of the safest countries on the planet. Alas, the numbers indicate otherwise.

And yet, despite the political war one would have to wage to enact change in the direction of peace or the stopping of arms proliferation, H.H. the Dalai Lama suggests a series of concepts to be understood and adopted by all those who, despise living in fear, are earnestly interested in striving for peace.

First, that a solution to problems in the Middle East with terror groups like ISIS must be approached using secular ethics – i.e., the “promotion of human values such as compassion, forgiveness, tolerance, contentment and self-discipline” outside the realm of religious edict or practice. Meaning that people of all faiths should embrace the quantifiable fact that we are first human, and then spiritual. To the Dalai Lama, “it is not enough simply to pray.” What he calls “mechanisms for dialogue” must be created, as well as ways to give perspective and an education in morality to those who have little of either outside their limited religious experiences.

Next, that we as individuals can make the conscious effort to be more sincerely compassionate – first with our friends, but more importantly with those we consider opponents. This is a message almost as timeless as the Lama tradition itself, one articulated well by His Holiness: “Love and compassion are necessities, not luxuries. Without them, humanity cannot survive.”

It’s clear the Dalai Lama’s mission is to make the world as happy and peaceful a place as possible. In classic Buddhist fashion, he strives, for himself and for others, to simply alleviate suffering. In doing so, he’s come close to figuring out what is best for the future of humankind: the promotion of equality, of religious tolerance and non-violence, of treating each other as if we were beings of love and not hate.

Indeed, the Dalai Lama’s mission is to teach us to stand on the side of those who love, and with patience and sadness renounce the people and communities who make a regular practice of committing evil. The anti-examples of who we should strive to be like, are those who kill for hate. The Dalai Lama, in his uniquely open-minded and considerate way, has embodied his own peace-loving, inclusive philosophy. We should commend him for it, and try to follow his example.