Sept. 5 through Sept. 11 is National Suicide Prevention Week. Suicide — especially youth suicide — is a huge issue here in Utah. Many reasons have been posited for this, but one in particular stands out: Utah’s treatment of the LGBTQ+ community, which starts when people are young and for many doesn’t end.

Randall Lake is an artist currently living in Utah, as well as an alumnus of the U and a former art teacher. His insightful, striking and controversial work bears direct testimony to the ways suicide has touched his own life, as well as the ways those instances were influenced by a world that has been historically unkind to LGTBQ+ populations. It seemed apt to include a bit of his story this week.

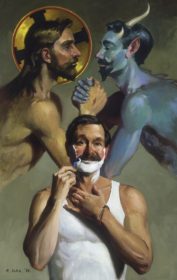

Currently a non-member and an openly homosexual man, Lake has an interesting history. He converted to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints at a time when he knew he was gay and wanted more than anything else to not be.

“I joined the church in Paris because I read this ‘Miracle of Forgiveness’ book and it said if you changed everything — all your friends, get married in the temple, then you’ll be straight — and I wanted to be straight more than anything,” Lake said before adding, “but it’s like praying for blue eyes when your eyes are brown.”

While this is clear to him now, it certainly wasn’t then. Straightness was all he wanted.

From a young age, he explained, he knew he was gay, and he knew it wasn’t what his parents wanted from him. “I was born in 1947 in Republican Newport Beach, my parents were upper-middle class, they didn’t know what to do with me,” Lake said.

The damage done by this treatment, by this attitude, led to him thinking he was “worthless.”

“I had no self-esteem because I was playing a role and I felt terribly guilty about my urges, my orientation. And at that time there were no role models […] Everybody was in the closet.”

It is this history, tied to the loss of two previous partners to suicide, that informs his current artwork.

“I’m a gay activist,” he said, “but I don’t march or go on committees; I do it through my art.”

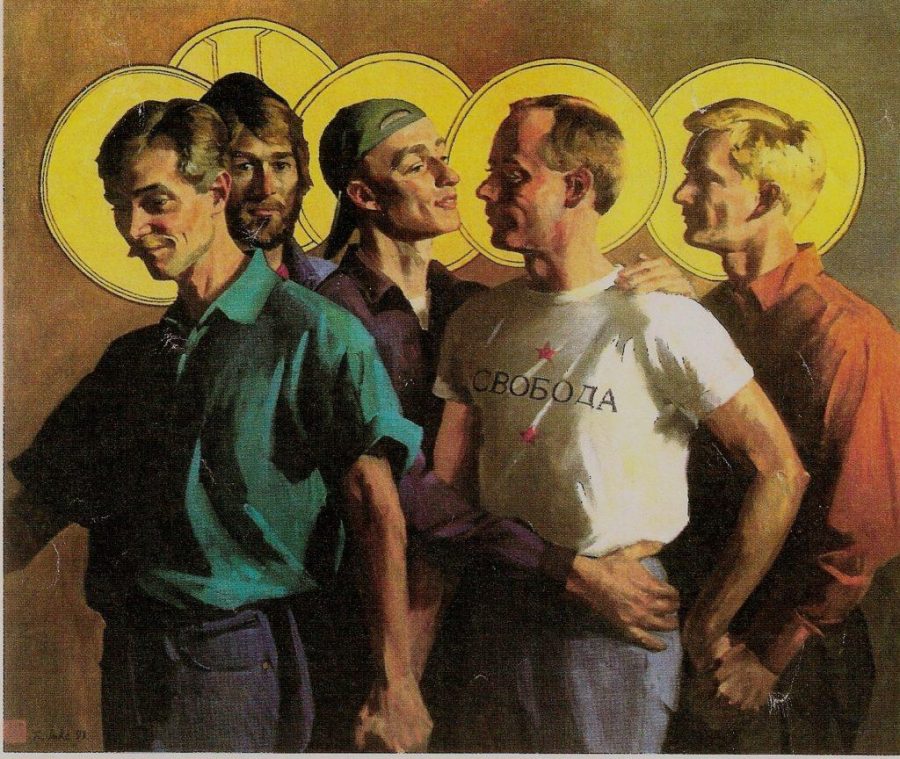

The art in question is plentiful, and undoubtedly thought-provoking. One titled “Safe in the Fold,” is a biographical piece about gay LDS men who marry in the church and have children — a practice Lake himself participated in.

Much of his purpose with this art is to make the existence of LGBTQ+ people and the relationships they have commonplace. He spoke of his hero, a French artist named Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, who rented rooms in brothels and painted the prostitutes he saw there as they did ordinary everyday activities like sleeping, getting ready and relaxing. At the time that Toulouse-Lautrec was producing this work, it was seen as naughty and something the interested gentlemen had to hide away in a back corner of their apartment. Nowadays the exact same type of work is on prominent display in famous museums like the Chicago Institute of Art.

Lake sees promise in doing the same thing Toulouse-Lautrec did but with gay people. “The only thing the media focuses on are the extremes,” he said, “the promiscuity and everything, and nobody gets any attention that pays their bills, mows the lawn, are committed, are monogamous.” So he did a whole series of paintings on just that: the normalcy of a gay existence.

“I just wanted to convey that we’re just normal people.”

Today, though suicide rates are high, and treatment of LGBTQ+ people still needs significant work, Lake seems hopeful.

“I think Utah’s made fantastic strides to come to terms with this, you know, we should celebrate diversity,” he said.

“I love this quote from ‘Biloxi Blues’, a book by author Neil Simon, and he said, ‘Never underestimate the stimulation of eccentricity.’”