The death penalty is a crude, antiquated form of punishment that should be entirely disavowed.

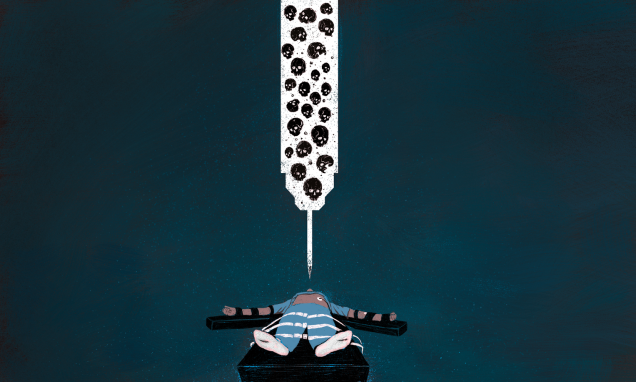

On Thursday, April 27, Kenneth Williams took his last breath as he lay strapped to a bed in a musty prison room. The execution chamber, which resides in Arkansas’s Cummins Unit penitentiary, is lit with flickering florescent lights. A small team of medical personnel, prison staff and spiritual advisors wait for the intensive procedure to begin. On that night, Williams awaited a “chemical cocktail” that numbed his body and stopped his heart — a fitting end for a man convicted of murdering three innocent souls, right?

Williams’ execution came second out of four inmate executions. Prior to these, Arkansas had not put a prisoner to death since 2005. Yet on April 17, Governor Asa Hutchinson ordered prison officials to execute eight men over the course of 10 days. Why? Well, according to Hutchinson, the state’s supply of a necessary sedative was set to expire at month’s end. Midazolam, which is particularly difficult to manufacture, has a tenured history of unpredictable outcomes. Regardless, Hutchinson pressed forward with the timeline which strongly resembled an assembly-line of death.

Although four of the eight inmates evaded execution via court orders, the rest were given only a few days’ notice. The process began with prisoner Ledell Lee, who was sentenced for murdering his neighbor in 1993. While each of these men likely deserved an early death, the process of executing prisoners is unwarranted and borderline inhumane. According to a study conducted by the British Journal of American Legal Studies, approximately 270 executions between 1900-2010 involved “departures from the protocol of killing someone sentenced to death.” Undeniably, many sentenced to death are guilty. The legal system, however, is far from perfect.

Indeed, there remains a chance that one innocent inmate ultimately suffers an excruciating fate. Williams, who was sentenced for killing a cheerleader and two law enforcement officials in broad daylight, was one who likely deserved punishment. Splayed on a padded table, Williams had a lethal injection pushed into his veins as an audience watched through a glass window. However, three minutes after the midazolam entered his system, he began convulsing violently. One Associated Press reporter, Kelly Kissel, who was present for the event, described it as, “the most I’ve seen an inmate move three or four minutes in.” During several agonizing minutes, Williams apparently coughed, convulsed, lurched, jerked. During a later press briefing, Hutchinson said that Williams coughed without sound, and that an independent review was not necessary.

No report will be prepared for public record.

Instances of lethal injections gone awry are not isolated. In 1985, inmate Stephen Morin suffered an excruciating death as medical personnel took 40 minutes to administer the injection. Four years later, Stephen McCoy had an allergic reaction, which left him writhing from pain in his tethers. Similarly, prisoner Brian Steckel had his IV accidentally blocked in 2005, which prevented the sedatives from entering his body. Witnesses reportedly heard his anguishing screams through the glass, despite the microphone being turned off. Yet, these incidents pale in comparison to the infamous execution of Clayton Lockett in 2014. Unbeknownst to the prison’s officials, his IV apparently “blew open,” which left Lockett squirming on the table for approximately 43 minutes. Although the medical staff eventually found the equipment issue, the pain from his partial dosage caused him to have a fatal heart attack.

Some posit that a murderous individual should be granted no pity; however, this position directly contradicts the Eighth Amendment to the United States Constitution. Written plainly, the amendment states that “cruel and unusual punishments [shall not be] inflicted.” Supreme Court Justice William Brennan agreed in 1972 when he wrote, “The ‘essential predicate’ is ‘that a punishment must not by its severity be degrading to human dignity.’” Regardless of guilt, it is unconstitutional to inflict punishment that leaves a prisoner suffering.

Beyond questions of legality, states with capital punishment programs are forced to pay escalating costs. According to FiveThirtyEight, there are six main factors that influence the price of executions: increasing attorney salaries, the cost of experts, outcome unpredictability, mitigation, jury compensation and prisoner housing. In Oregon, enforcing the death penalty costs twice the amount of sentencing a defendant to life in prison. Nebraska spends $14.6 million per year to maintain its program. On a macro-level, states with capital punishment spend $23.2 million per year more, thereby increasing spending by an average of 0.61 percent. In Pennsylvania, executions cost roughly $272 million per inmate. These costs are difficult to imagine, let alone justify.

However, while it is effortless to condemn expense, one must not forget the emotional impacts associated with the practice. Often, inmates remain on death row for years, which leaves the victim’s family waiting for closure. In numerous prisons, it can be difficult to source qualified individuals to oversee executions; therefore, the same group of personnel is recycled for numerous cases. Similar to combat, watching an inmate pass away can induce post traumatic stress disorder, especially if a lethal injection is botched. And for public defenders, who typically represent death row inmates, it is difficult to adequately represent each inmate. In Arkansas, this meant that several of the eight prisoners selected by the Governor were represented by the same lawyer.

The disastrous nature of capital punishment is evident, and the excessive financial and emotional burdens are unsustainable. Instead of using the death penalty, states should invest in alternate forms of justice. Sentencing a defendant to life in prison is 48 percent less expensive than imparting the death penalty. In North Carolina, this equates to nearly $2.16 million more per execution. Nationally, since executions were resumed in 1976, an extra $1 billion has been spent over sentencing prisoners to life terms.

Rather than funding capital punishment programs, states should prefer life imprisonment as an alternative form of punishment. Although there is a finite amount of space that prisons can handle, the financial savings could be funneled into prevention programs. Community-based mental health programs, which treat patients before they act violently, would reduce the number of convicted criminals. Furthermore, states could better support early childhood education programs, which aid at-risk youth. Instead of dealing with the outcomes of violence, law enforcement officials would partner with the community to lower crime. Indeed, there are numerous alternatives to capital punishment. Forcing inmates to suffer for extended periods of time? Simply barbaric, antiquated and costly.