The University of Utah has approximately 18,758 parking spaces on campus, but according to commuter services director Alma Allred, the U sells about three times more permits than spaces — they figure each space will handle more than one person per day. That number, however, excludes limited lots at Research Park, University of Utah Health, Fort Douglas and the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints Institute buildng. If those areas are included, the total number of parking spots is 29,676 spaces.

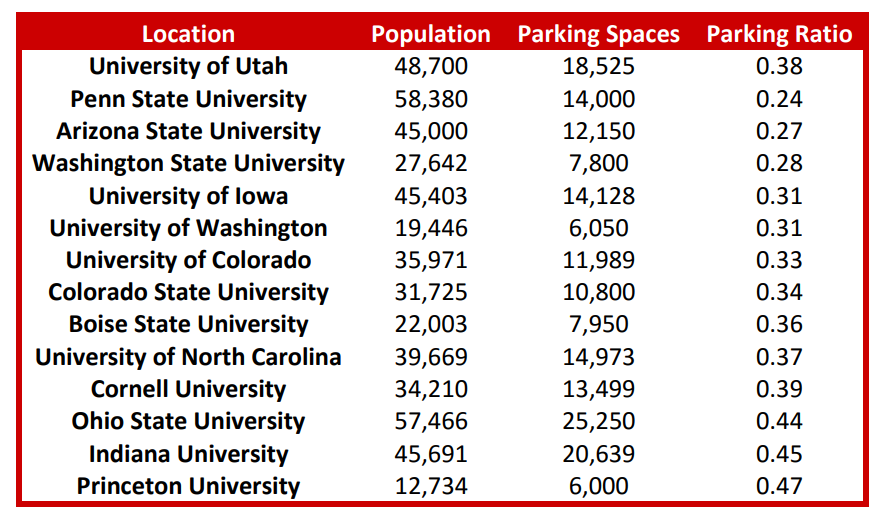

With a campus population of about 48,700, the ratio of spaces to users is 0.38. According to the U’s proposed Transportation Master Plan — which has yet to be approved by the Board of Regents — a number less than 0.3 spaces per user “either indicates a system that is deficient on parking or highly successful in implementing alternative transportation measures,” and a number greater than 0.5 spaces per user “indicates a system that is highly dependent on automobile travel.”

Schools like Arizona State University, the University of Washington and the University of Colorado have lower parking ratios than the U as a result of having implemented programs that increase accessibility to campus through alternate modes of transportation. Allred said he’s comfortable with the ratio as it stands today. There are more parking spaces per user than ever in his time at the U.

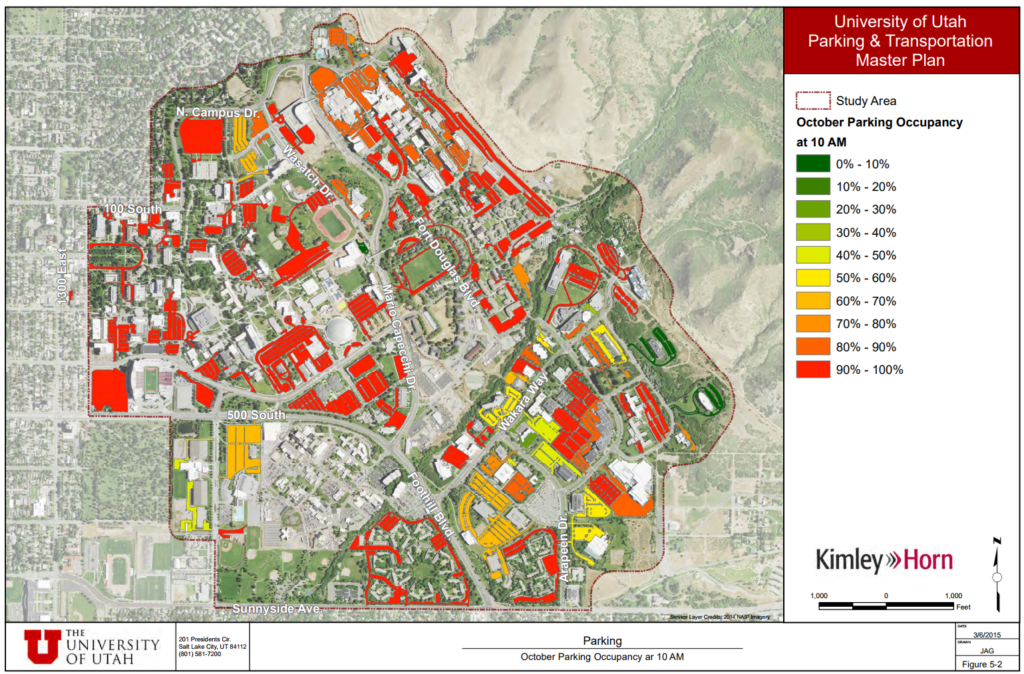

Having an acceptable ratio of parking spaces to users, however, doesn’t mean there aren’t any parking issues. The plan also says, “Many of the existing parking facilities on campus are at or near capacity during peak conditions.”

The U estimates demand to currently stand at 27,175 spaces if Research Park and the hospital are included. This means there is currently a surplus of 2,501 spaces on campus. However, they acknowledge in the master plan that a great deal of that available parking is in Research Park, which is anywhere from one to three miles away from buildings on main campus. The document says there is a demand for about 500 more spaces on main campus and near dorms.

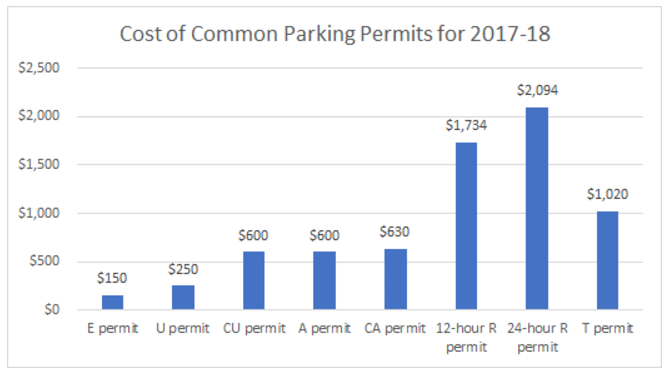

Complaints haven’t just been about finding parking spots, though. Students, faculty and staff have been frustrated with the cost of permits. The price of a U permit for the 2017-18 year is $250, $150 for E. If a student wants to park in a garage, it’s $600. Faculty and staff members have access to more convenient spots, but the rates are higher. An A permit costs $600. Reserved spots are $1,734, and they are held for 12 hours per day. If a faculty member wants a 24-hour reserved spot, they’ll pay $2,094. The cost of T permits for hospital employees is $1,020.

Not only are these unaffordable for some, but the prices are also higher than they’ve been in the past seven years. Allred said this is because commuter services has to raise the price to pay for more parking structures. By law, parking at state universities must be self-funded, meaning that it can’t be subsidized by tuition or taxes.

While the main mode of transportation to the U is car, not everyone drives. Thirteen percent of students live on campus, while 37.5 percent use UTA systems like TRAX, Frontrunner and buses. In fact, the U is the number one user for UTA.

Complicated Decisions

Parking at the U is more complicated than building spaces for every car. Allred called it a “balancing act.”

“The sustainability lobby prefers that we reduce the number of parking spaces and force people to mass transit,” said John McNary, the former director of campus design and construction. “The public affairs lobby prefers that we provide more parking to make it a better visitor experience. There are other lobbies with their opinions, such as the athletic lobby, the academic lobby, the clinical lobby, the faculty lobby, the entertainment and performances lobby, all of which have their opinion regarding parking.”

Many people want parking that’s cheaper and more convenient. Another group wants less parking on campus, because it has negative environmental impacts. Community members who live near the U want all driving on campus decreased, because roads are packed with students and cars are frequently parked in front of their houses.

McNary explained parking plans aren’t only determined by demand, but also by cost, the needs of interest groups and parking at institutions similar to the U.

Paying to construct parking is difficult with no outside funding. A parking garage costs between $10-12 million, and it lasts about 20 years. This leaves the price tag at about $21,000 per parking space. A surface lot costs about $3,500 per space and lasts only five to six years. Those estimates only include construction costs, not maintenance, insurance or lighting.

Donors could give money to the university for this specific purpose, but Allred said no one ever has. The U’s communication director, Christopher Nelson, said the only exception to that is large projects like the Huntsman Cancer Institute, which included a parking structure as part of the overall project.

“There are no simple answers in parking, and parking supply is not determined by planners in a vacuum, believe me,” McNary said.

Complicated Solutions

The Transportation Master Plan called the construction of new lots the most common solution, but said it’s not cost effective or environmentally-friendly. It said more parking “may not be sustainable in the long run, as land becomes scarce or population demands necessitate more and more parking.”

Parking lots can’t just be built anywhere on campus, either. For instance, there is a grassy field east of the Union which is sometimes used for parking during sporting events. Even getting that lot paved, according to Allred, would be complicated.

“Getting permission to pave landscaped areas on campus is like asking to organize a hunting party for bald eagles,” he said. “It just isn’t done. There would be so many steps involved — getting a variance from the master plan is only one step — that it wouldn’t be feasible.”

The plan said that ideally, parking on main campus would go beyond satisfying current demands to provide a 10 percent surplus. This would require 2,171 more spaces. Referring to two locations in which parking garages could be built, the plan said, “Even with these two locations, the university cannot realize the parking supply needed to offset the surplus issues on campus. This study does not recommend that constructing new parking facilities be the primary means of supporting new on-campus demands.”

Nonetheless, commuter services will add 2,001 new spaces on campus, bringing the surplus to about 8 percent. According to the master plan, “This small surplus is not enough to operate the parking system efficiently and will likely create problems as additional campus changes are evaluated.”

According to the plan, any proposals for fixing the problems with commuting to campus by car must account for the future. Enrollment will likely grow by nearly 10,000 before 2040, putting more strain on the school’s infrastructure. Additionally, two parking lots containing a total of 411 parking spaces are already slated for demolition in the next five years.

The U has many goals for coping with these pressures, but the biggest is to decrease all vehicular traffic to the U by 20 percent. The university hopes to reevaluate the permit system in order to prioritize between groups based on who needs parking most.

One approach the U is considering is restricting all permit types based on campus access, similar to a system at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. If a student doesn’t live on campus but does live within a mile of the center of campus, they would not be able to purchase any kind of permit. Only a certain number of permits would be provided for each class, and freshmen couldn’t buy permits for on-campus parking, but would have access to lots at shuttle stops on the edge of campus.

The plans say these changes would encourage students to use mass transit and other modes of transportation, like walking or biking. They estimate it would require the construction of only 600 to 1,200 spaces rather than 2,171.

The U also hopes to open up restricted lots in Research Park. Those lots have a 24 percent surplus, with some lots staying below 50 percent occupation even during the busiest times of the day. Within the next five years, they think those lots will remain below 75 percent full. They suggest providing shuttling services for lots further than an easy walking distance, allowing them to provide an additional 2,251 spaces.

The U further hopes to make parking on campus easier by eventually “implementing guidance and wayfinding systems.” This could include smartphone apps and space detection systems which would communicate information about parking lots including their locations, rates and the availability of spaces inside. This system would involve a large monetary investment and would require parking lots to serve only one type of permit rather than the current scheme with both A and U spots in a single lot. The U aims to convert to this approach as soon as possible.

To draw people away from parking and into other modes of transportation, the U proposes improving the experience of walkers and bikers, encouraging ridesharing and enhancing mass transit.

Commuter services plans to build more bus stop shelters and bike lanes, as well as provide more bike parking. The U also hopes to fill in the gaps where sidewalk and lighting is lacking. It will add 35,000 feet of sidewalk.

According to the Transportation Master Plan, the U has signed a three-year contract with Enterprise’s Zimride, a ridesharing program that helps students find others who are travelling from the same place. Students can also us Enterprise’s CarShare program on and around campus, which allows drivers to rent vehicles located at multiple parking locations by the hour.

In the master plan, the U advocates for significant expansions of UTA’s services to campus. Increases in mass transit services are known to increase ridership because “folks appreciate the convenience of being able to show up at a bus stop or train station without having to consult a schedule beforehand,” explained Leo Masic, an assistant service planner at UTA.

Perhaps most significantly, the U is pushing for the rumored TRAX Black Line. It would be a completely new line between either the airport and campus or Salt Lake Central and campus. The route would significantly increase the frequency of TRAX service at the U.

“Many things would need to be considered before any proposals are put forward,” Masic said. “A few challenges are apparent from the get go — engineering challenges with the half union rail track interchange at 400 South and Main Street, as well as having enough train cars to run a new line.”

The U’s documents say that, ideally, the Black Line would end at a new intermodal hub which would make transfers between all transportation modes simpler by bringing them to one building, which would be built near Rice-Eccles Stadium or the Huntsman Center.

Nearly all of these plans have barriers, especially in regard to costs, but even the biggest change — the Black Line — would not be enough to reach the U’s goals on its own.

“About one-third of the campus population lives on the southeast side of the Salt Lake Valley,” Allred said. “In order for UTA to capture that population, they would need to significantly increase north/south service along the east side of the valley — either in bus service or by expanding light rail.”

The Black Line would likely do little to serve that population. It would instead increase ridership by making TRAX use more convenient.

What’s most likely to happen is a mixture of some of these plans, which would result in more options for commuting to campus and less strain on the parking system. Allred said what they likely won’t do is decrease the costs of parking on campus.

@EliseAbril