Soda Springs, Idaho has been shaking this month due to a 5.3 magnitude earthquake that set off what appears to be a chain reaction of smaller quakes. Though there was only minimal damage in the area, subsequent reverberations have been felt as far south as Ogden. Of these 25 or so aftershocks, 23 are listed on the University of Utah’s seismology website as being 4.0 or greater. Although this magnitude may not be dangerous, it is still on the upper end of what seismologists consider a safe range — with 5.5 being the tacitly accepted threshold for minor damage.

However, these aftershocks have already given those living nearby some anxiety, and have brought up a number of questions about whether Utah is prepared for an earthquake and when it is due for “the big one.”

According to Keith Koper, the director of seismograph stations at the U, Utah experiences a seismic event of similar proportions to the one in Idaho about every 10 years. Subsequently there is the potential that a populated area could be hit. Residents along the Wasatch Front remain concerned, especially considering the numerous faults in the area that are coupled with Utah’s unique geology. However, some areas would experience more damage than others.

“As you go further west out into the valley you start to get some pretty weak soil,” Koper said.

He went on to elaborate that during an earthquake, the western parts of the Salt Lake Valley would likely go through liquefaction. This process is essentially when saturated soil on a large sand-table, like areas surrounding the Great Salt Lake, behaves like a liquid. In a state of liquefaction, the surface would lose its strength and structures such as buildings would slip, slide and possibly sink into the ground.

Koper said Utahns can best prepare for a potentially devastating earthquake by not hanging heavy objects above high-traffic areas, ensuring they have an ample supply of food and a water filter, as well as access to emergency supplies like flashlights, first-aid kits and sleeping bags. You would want “basically anything you would need for camping,” Koper said.

He also mentioned that one of the best ways to stay safe in the event of an earthquake is to keep inside and take cover under a table, because as he put it, “bricks and concrete are going to be falling off the buildings.”

Sometimes, though, these safety tips are going to fall short. After all, the average citizen can’t know when an earthquake is about to happen. There is a massive amount of information required to tell at any given time how Earth’s crust is behaving, so it makes sense that predicting where an earthquake is going to occur is nearly impossible. Therefore, scientists have to rely on a number of tools to warn the population.

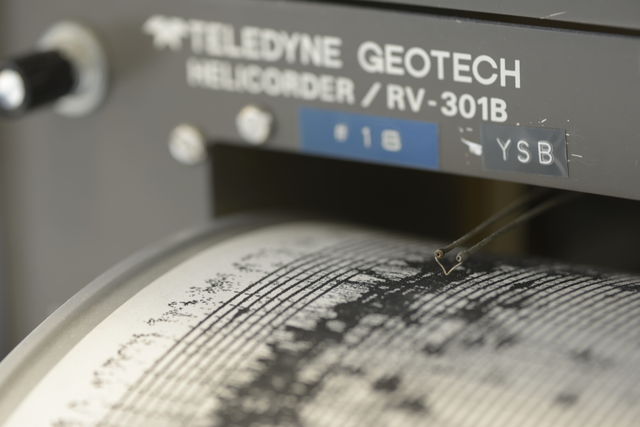

The length of detection time from measuring seismic waves can be anywhere from seconds to a couple minutes before the earthquake actually strikes. To increase this short amount of time, seismologists use seismometers, which have been deployed to measure the ongoing quakes in Idaho. In addition to the seismic waves themselves, seismologists use the equipment to measure the depth of quakes, as well as the location of faults under the Earth’s surface.

“When you see that lightning bolt, you know the thunders going to come,” said Koper. “You don’t need to set up an atmospheric model to tell you that,”

s.morgan@dailyutahchronicle.com