As hurricanes wreak havoc in the Caribbean this hurricane season, tearing up coastlines and flooding cities, University of Utah weather researcher and professor, Zhaoxia Pu, works to improve hurricane forecasting systems and minimize the damages that result from these colossal storms.

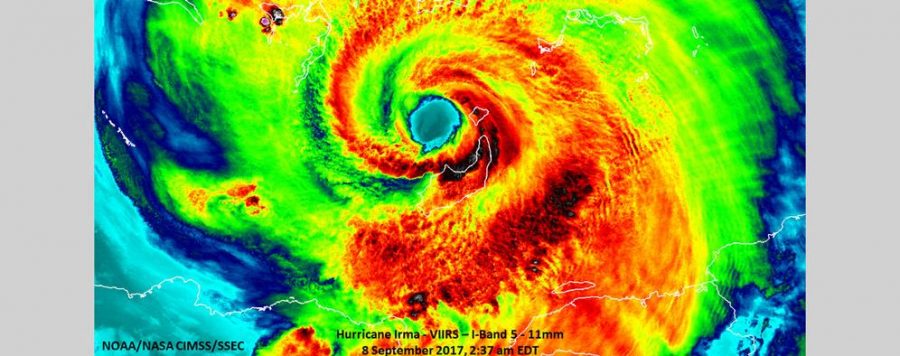

The 2017 hurricane season has certainly been one for the books. Between 1851-2015 there were only three category 5 hurricanes, 18 category 4 hurricanes, and 76 category 3. The recent hurricane Irma was a category 5. Along with Harvey (a category 4), Jose, Maria, and numerous other smaller storms, 2017 is one of the most active hurricane seasons in the past century. The billions of dollars in damages and massive impacts on people’s lives in hurricane-prone regions only serves to further motivate Pu and her colleagues to refine storm prediction science.

Professor Pu initially became interested in weather and hurricane forecasting due to an interest in major weather events themselves. Hurricanes, tornados, and heavy rainfall cause floods that threaten life and property, as well as having high social and economic impacts. Accurate weather forecasting mitigates the losses resulting from these natural disasters.

Around the world, numerical weather predictions made by computer models are the central guidelines for hurricane forecasting, as well as daily weather forecasting. Using thermodynamics and physics, forecasters create models that predict how storms may change with time.

“The basic principle of the numerical weather prediction is to solve a set of partial differential equations that govern the motion and evolution of the atmosphere,” Pu explained. “The computer weather models are made to play this function using numerical methods. They take current atmospheric conditions as inputs and produce the forecasts by integrating the computer model forward.”

Computer models are not perfect, however, and current atmospheric conditions may not be accurately described due to insufficient information. Therefore, forecasting often has uncertainties. “To mitigate the uncertainties of forecast,” Pu added. “[We use] ensemble forecasting, which involves a group of forecasts generated either by multiple computer models or by a single model, starting with multiple initial conditions. [This method] is usually used for the daily forecasting. The ensemble forecasting not only provides a set of forecasts but also provides forecast uncertainty information and the probability of occurrence of a certain event.”

Pu’s research involves developing better approaches for utilizing the available conventional, satellite and radar observations to form the best possible input values (initial conditions) for the numerical weather prediction model. She focuses on the more accurate assimilation of data to create models. “Some of my research work is also dedicated to [improving] the computer model itself, especially [the] parameters that help to better describe the physical processes inside of computer models.”

As with all weather forecasting, hurricanes are an inexact science and knowing exactly what these unpredictable weather events will do is very difficult. Still, with each passing hurricane season, Pu and her colleagues grow closer to certainty with weather forecast models.

c.macdonald@dailyutahchronicle.com