University of Utah biochemistry professor Janet Iwasa spent months in Hollywood learning to animate so that she and other researchers could visualize molecules in a new way. Now, she spends months building complex molecular models on her computer.

“Why were we all relying on simplistic sketches — representing molecules as circles or squares, for example — when we could be creating three-dimensional and dynamic animations of how we thought things might actually look?” Iwasa asked. “So I started taking animation classes and created my first scientific animations of what my lab studied.”

Scientists know much more about cells than what can be seen in a two-dimensional model. Iwasa was working toward her Ph.D. in cell biology at the University of California, San Francisco, when she first came across the blending of animation and science.

“In cell and molecular biology, many of us are trying to imagine how different cellular processes work at a molecular level,” Iwasa said. “These processes often involve numerous proteins all moving around, interacting with each other, changing shape and sometimes forming larger complexes. It can be hard to wrap your head around things like this when there can be so many moving parts. That’s where animation can come in and help researchers explore how a process might occur.”

Iwasa calls this “visual hypotheses,” or in other words, models of ideas that are based on scientific data and allow researchers to interact with and test the theories optically. This new concept offers a new look into cellular processes and takes scientists a step further in gaining a better understanding of what makes up the world around us.

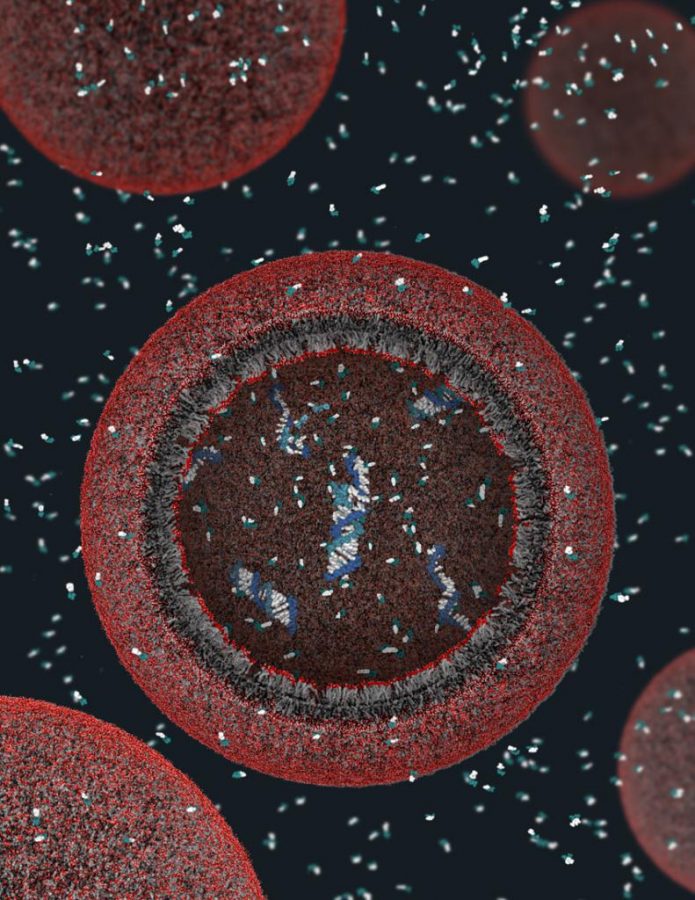

A great deal of research goes into each of Iwasa’s projects. One of Iwasa’s current projects is working on demonstrating the molecular life cycle of HIV. For this, Iwasa takes into account over 20 years of research into understanding how HIV works at the molecular level so that she can accurately create a detailed animation of what the international science community knows about HIV. The 10-minute film is expected to be released in the spring.

Over the years, Iwasa has gained recognition for her work from numerous media outlets and science organizations, including Foreign Policy, Fast Company, TED and the National Science Foundation. Having published 13 animations, Iwasa is keeping busy with not only developing more, but also teaching up-and-coming scientists.

“I’m co-teaching this class with professor Lien Fan Shen in the Film and Media Arts Department,” Iwasa said. “The course is called Animating Biology, and in it, groups of students — generally coming from either art or biology backgrounds — are working together with a faculty member or a local biotech company to create a scientific animation. It’s been a lot of fun, and we’re hoping to continue this course in the future to train a new generation of scientific animators.”

Iwasa hopes scientific animations continue to gain traction, as she feels they have the potential to break down barriers between the general population and the scientific community.

“Molecular animations can give people a fascinating window into what a scientist thinks without letting things like jargon get in the way,” Iwasa said.

@kenzomcd