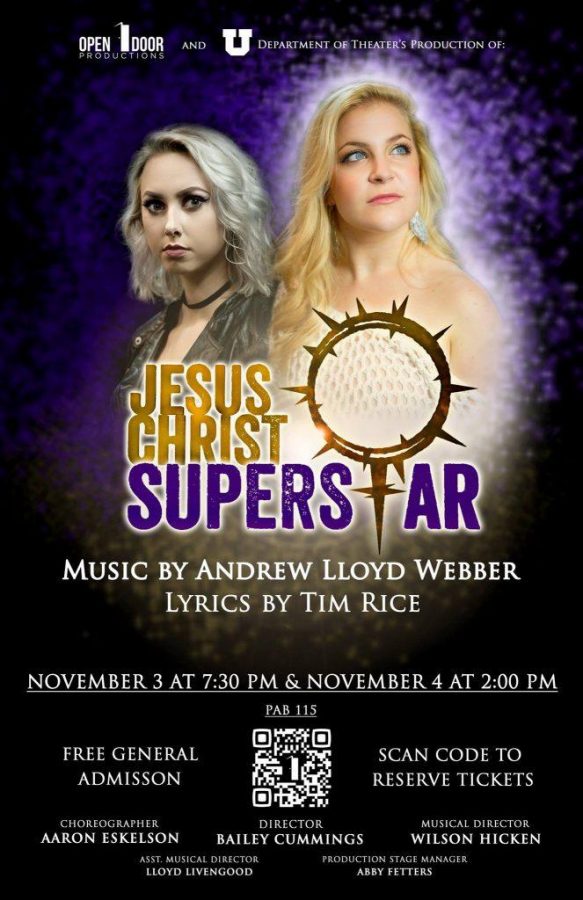

On Nov. 3 and 4, a sold-out crowd gathered in the Performing Arts Building (PAB 115) to watch the University of Utah Theatre Department’s production of “Jesus Christ Superstar.” The musical, written by Andrew Lloyd Webber and Tim Rice, is a rock opera that interprets the biblical story of Jesus Christ, largely focusing on the rivalry between Jesus and Judas Iscariot. Since its Broadway debut in 1971, the show has been a favorite among theater companies. This production, however, stood out for a couple reasons. All characters including Jesus, Judas and the apostles were played by women, and the show was entirely directed and produced by a University of Utah student.

Director and producer, Bailey Cummings, worked tirelessly to bring his vision to the stage. Though the show had a quick rehearsal process (the actors worked together for less than a month), Cummings’s preliminary idea for the show came years earlier. Initially, he had never been particularly interested in “Jesus Christ Superstar” until three years ago when he was in the car with his roommates and friends, Jamie Landrum and Amanda Wright, and the song “The Last Supper” from the musical came up.

“They both realized in that moment that they both loved the show so much and thought that it would be really cool to be in a gender-swapped version of the show, where Jesus and Judas are played by females,” Cummings said.

Cummings realized that presenting “Jesus Christ Superstar” with an all-female cast could lead to an exciting new interpretation. He recognized that Jesus and Judas were ideal roles for Landrum, who played Judas, and Wright, who played Jesus, and casting women would make the show unique. As he was creating the show, he realized his casting choices made this production “Jesus Christ Superstar” fundamentally different.

“When you see ‘Jesus Christ Superstar’ in a traditional cast, it all comes out of this power struggle: who’s right and who’s wrong. With our cast, there was a tenderness I had never seen present before,” Cummings said. “We really found the love in it. … Judas turns Jesus over because he loves him so much that Judas can’t let Jesus go through with this superstar image that he has created for himself. … That’s why I think this production specifically is different and relevant.”

Building this original idea into a full-scale production was a major undertaking, and working through the challenges of directing and producing was a learning process. After talking with a faculty advisor about his goals, Cummings spent the summer setting preliminary plans of production in place. He had to secure a performance space. He had to discuss grant funding with department faculty and come up with a plan for fundraising. Most importantly, he had to navigate purchasing the rights to perform the show.

The process of obtaining rights is difficult, and it almost stopped Cummings. After weeks of negotiating with a new production company, he had a contract to produce the show. There was a catch, however, the initial payment was $1,200. Without a production budget or a grant in place, Cummings did not have a way to make the payment on time. He was ready to give up, but Landrum “did not take ‘no’ for an answer.” She motivated him to move forward, and she helped him manage rights and scheduling. With that added push and several weeks of planning, “Jesus Christ Superstar” was ready for rehearsal.

To aid in his rehearsal process, Cummings enlisted other students to round out the creative team and help manage the production. Like his director, choreographer Aaron Eskelson, came into “Jesus Christ Superstar” as a newcomer: he had never choreographed a full production before, and had never seriously pursued the art form outside the classroom. But both men agree that their collaboration was an effective addition to the show. Eskelson viewed his choreography as a chance to keep the show entertaining and lighthearted while also developing character. And Cummings found Eskelson’s work was essential to the show’s success. The dancing fit perfectly into his vision for the production, and Eskelson was also able to help address the many challenges facing the production.

The rehearsal process was both difficult and exciting. The production faced numerous logistical challenges — most notably, the material had to be adapted to fit PAB 115, a small space with limited seating. “Jesus Christ Superstar” traditionally features large-scale production elements and is usually staged in an arena or an auditorium.

Cummings had to get creative: He staged the climax of the musical, Jesus’s crucifixion, without an actual cross. Instead, Wright pushed two large staircases upstage and then stood in a position that looked like she held up the staircases. Then, a live drummer played beats mimicking the sound of nails on the cross as Wright stood alone with a single spotlight.

“It was not what I initially wanted to do with the scene, but it actually looked a lot better than what I wanted,” Cummings said.

Even as Cummings learned to think on his feet and adapt, there were still many stressful moments. With only a month of practice before opening, rehearsals had to be fast-paced and efficient. Cummings had to learn to hold a position of authority over fellow students and some friends. For the first two or three rehearsals, Cummings felt it was sometimes uncomfortable for everyone to get used to this dichotomy. Eskelson agreed, and found that taking input from too many people led to confusion and frustration. After some practice, Cummings and Eskelson learned to strike a balance.

“To gain respect you have to give respect,” Eskelson said.

One unexpected challenge was particularly sobering. During rehearsal on Oct. 30, the students in the show were shaken up after the tragic shooting of U student ChenWei Guo. Rehearsals were canceled out of concern for the actors’ safety, and the event was frightening and emotional for many involved in the show. The performances were later dedicated to the memory of Guo.

After months of hard work, Cummings was ready to see his vision come to fruition.

“[It was] the most terrifying opening I have ever had,” Cummings said. “As a director, you just have to let go, and it’s really hard to do that.”

The performance went off without a hitch, and Cummings was thrilled to watch his hard work pay off. The show was also well received by the audience: Cummings pointed out with pride that several were moved to tears.

Eskelson similarly found his work on the show to be rewarding and enlightening. He says the process taught him to relax and to trust his cast, and he discovered a passion for choreography that he had never noticed before.

“I never wanted to pursue choreography, but now that I have done it, I really fell in love with it,” Eskelson said. “I just want to do more and figure out more and figure out my style.”

Looking back, Eskelson’s favorite memory is working with the cast, feeding off their positive responses and working through their vulnerability to create the best show possible.

Cummings may be finished with “Jesus Christ Superstar,” but his work on the production has led to more beginnings than endings. The success of the show inspired the creation of a student production company at the U. Cummings currently serves as the artistic director, and his goal is to mentor students who want to direct existing plays or musicals in “new or inventive ways.” He is willing to listen to anyone who has a creative idea, and he hopes to present a new production either this spring or summer. Using his experiences with “Jesus Christ Superstar,” Cummings is poised to usher in a wave of student innovation and creativity.

In the Stephen Sondheim musical “Merrily We Roll Along”, a song appears in Act II that considers the thirst for creativity and the need to make art. In one portion of the song, the characters sing: “We’re opening doors, singing, ‘Here we are!’/ We’re filling up days on a dime/ That faraway shore’s looking not too far/ We’re following every star/ There’s not enough time!”

Despite the many obstacles he faced, Cummings worked to follow his passion and create something meaningful. And along the way, he has opened new doors for himself, for the other students he worked with, and for future students who want to create their own ideas. It’s fitting then, that Cummings’ new company is called Open Door Productions.

If Cummings has proved anything, it is that the door is always open to achieve difficult goals, break new ground, and redefine what’s possible.

j.petersen@dailyutahchronicle.com

@JoshPetersen7