When I first moved to Salt Lake City, I didn’t have a car. While I felt at a loss, I realized it was a blessing in disguise. Through my personal transportation crisis, I found a love for biking. However, my bike commute left me vulnerable to the elements and to the poor air quality we face in the Salt Lake Valley during inversions. Like many bikers, runners, rollerbladers, longboarders, what have you, I experienced severe lightheadedness, shortness of breath and fits of coughing because of the smog that constantly surrounds us in the weeks between storms. I used to think of the air quality as a conditional living hazard because of the location of Salt Lake City and its bowl-like surroundings, we were bound to be trapped by the toxins of other, more wasteful cities. However, we are reaping what we sow when it comes to air quality.

Every year, the Environmental Protection Agency releases a report called the Toxics Release Inventory (TRI). This data describes how many pounds of toxic chemicals each state and county in the country produce. I wish this document contained good news about Salt Lake City’s air quality. I wish that even though we rank sixth in the American Lung Association’s Top 10 U.S. Cities Most Polluted by Short-Term Particle Pollution for 2016, we weren’t producing toxins at the same rate as surrounding metropolitan areas. For anyone who has driven down the Cottonwood canyons in March three weeks after a storm, you know those hopes could only be that: wishful thinking.

From 7 miles up in Little Cottonwood, you cannot make out one building in downtown Salt Lake City when inversion has set in. The TRI found Salt Lake County released 250 million pounds of toxic chemicals in 2016, nearly 150 percent more toxic waste than the next most contaminating county, Humboldt County in Nevada. These chemicals can contaminate our drinking water and air, potentially causing cancer or other chronic human health effects, adverse acute human health effects and significant environmental effects. I’m not here to lecture anyone on climate change or make a political statement in our sports section, but if we don’t start taking care of our air, we could put athletes and ourselves in danger.

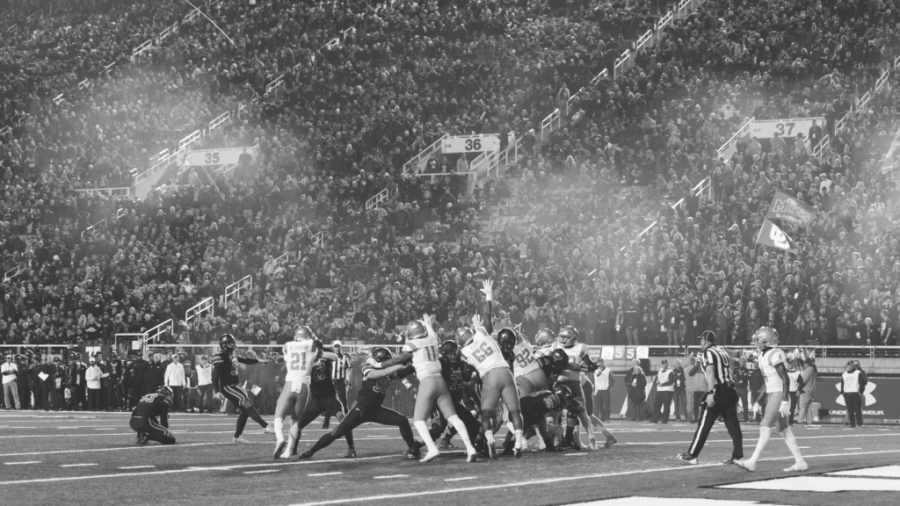

Luckily for me and many other recreational sportsmen and women in Salt Lake City, there are plenty of respirator and air-pollution masks on Amazon to choose from, but what about the athletes in Salt Lake City and at the University of Utah who can’t wear these masks? What about the football or soccer teams? Communication is key in these sports, and obstructing speech with a mask is not an option. These students take on a massive workload and an incredible amount of responsibility to play their sport. Now, there is the added concern of lung and cardiovascular health as a result of inversions. These athletes could be plagued by these adverse health effects for years to come.

Some of these athletes can’t afford to compromise their bodies as they anticipate a professional sports career. Harmful chemicals in the air, such as ozone, can impact lung function and potentially cause asthma or cancer. The men and women who wish to represent the U on the field can’t be disadvantaged as one small impediment to their health could be the difference between a 12-year career and a 2-year career at the professional level.

The air quality in Salt Lake City could also put the Utes behind the 8-ball in the short term. These players host half of their games at home, and they then have to practice in their home facilities, meaning they are constantly breathing in the polluted air. Breathing ozone-riddled air for long periods of time could hurt an individual’s performance, potentially tanking their stats. This would most likely be felt in the final minutes of a game where fitness is paramount and big-play ability is truly measured. Scouts and coaches may account for how air quality affects players, but I think it’s safe to say that most don’t. So when they see that an athlete has failed to put up yards in the final quarter of a game or has only scored one goal in the second half all season, they may begin to question their stamina and impact as contests come down to the wire.

For the most part, we breathe air that won’t poison us and we can get away from pollution in the mountains whenever we want. This problem isn’t getting better though, and we need to find solutions. For the foreseeable future, we will continue to use fossil fuels on a daily basis and these air quality issues will keep popping up with more severity. We need to be conscious of our impact on the environment for the community.