James Sugihara, a Japanese-American born in 1918, was the first student to graduate from the University of Utah with a doctorate degree in chemistry. Sugihara obtained his degree in 1947, after overcoming a number of difficulties and setbacks brought on by World War II and Japanese internment.

Early Life and Japanese Internment

Sugihara obtained his undergraduate degree at the University of California, Berkeley, where he received an honors Bachelor of Science in chemistry. He went on to pursue his graduate degree just as WWII started to heat up and discrimination toward Japanese-Americans intensified.

When he was an undergraduate in chemistry, Sugihara had never even dreamed of going into the academic field.

“I thought it would have been hilarious to become a professor,” Sugihara told North Dakota State University’s (NDSU) student newspaper One Herd. “I believed that route was closed to a student back then.”

Sugihara had hoped to go into the petroleum industry, working on chemical research in that field. One of his close friends, Vaughan Smith, took a research position with Chevron Corporation, one of the largest oil companies in the world. Sugihara wasn’t even invited to interview for the role, as Japanese-Americans at the time were generally not considered for employment in the American scientific community.

“This is the life of a kid that I felt I was pretty parallel with, coming from the same [academic] circumstances,” Sugihara told One Herd. “I went a different route — ended up going to graduate school, ended up in an academic position, academic administration, and I think if I were to compare notes in the end, I would have taken my path again.”

Before he could become employed in a research position, Pearl Harbor was attacked.

In December 1941, Japan dropped bombs on Naval Station Pearl Harbor in Hawaii. One of the ways the American Government reacted was by declaring everyone of Japanese descent living in the western United States a potential security risk and taking measures against them. Then-President Franklin Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 on Feb. 19, 1942, which authorized the forced relocation of 110,000 people of Japanese ancestry. They were sent to 10 inland internment camps.

Initially, he was forced onto a temporary holding facility at a horse racing track in San Francisco, along with 7,000 others. It was known as Tanforan. There he was made to share a bunk in horse stables that were crowded with other single men. It was also where he met his wife, May Murakami, to whom he is still married.

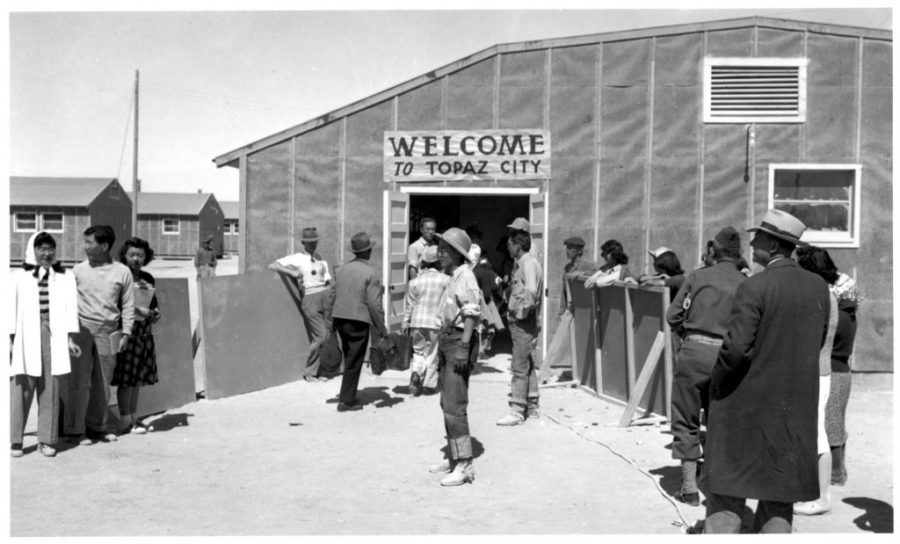

They were later relocated to Topaz Camp, which stood some 140 miles west of Salt Lake City.

“I was continuing on in graduate work and to have it disrupted was really kind of a blow,” Sugihara explained to the U’s Alumni Association magazine Continuum. “And to have it done in such a way where we were really treated like criminals, literally considered to be suspect to the national well-being on the basis of race only, was something that seemed totally irrational to us. We had always been led to believe that we were a nation where everyone was afforded certain rights, and we felt that this was a terrible violation. And I think history has shown that it was.”

The internment camps were surrounded in barbed wire and had armed guards tracking all activity. Though they couldn’t go back to the west coast, Japanese internees were allowed to leave provided that they found their own accommodations, work or were a full time student at a university. Their relocation also needed to be approved by the war department.

Sugihara was one of a few who were allowed to leave the internment camp and go to school. He was given a glowing recommendation by his graduate mentor at U.C. Berkeley and admitted as a graduate student and teaching assistant at the U beginning in winter quarter 1943.

Not long after that, Murakami found a position of work in Salt Lake City and was able to leave and take up residence there as well. They got married in June 1944, after Sugihara was hired as an instructor in chemistry at the U. Murakami and Sugihara recently celebrated their 70th anniversary.

Professional Life

Sugihara ascended the ranks and became a full professor at the U in 1955. Eight years later, however, another opportunity opened up in Fargo, North Dakota. He received a phone call requesting he apply to be the dean of NDSU’s chemistry department. At first he was skeptical, as he worried that North Dakota would be inhospitable toward Asian-Americans. He was pleasantly surprised by the welcoming reception once there and he found himself accepting the position as the next big move in his career.

Sugihara quickly found success in North Dakota, and in 1978 he was approached to go to what was then the USSR to speak with oil experts on geochemistry. There he provided consultation and assistance with research, representing the U.S.

In total, Sugihara spent 22 years at the U and another 25 years at NDSU. He established himself as a respectable researcher, scientist, teacher, and administrator. Research journals have published around 60 of his papers, and he has won numerous major research grants from private industry as well as the federal government.

Sugihara is thankful that the U let him in, as few universities were accepting Japanese students at the time. He has credited the university with giving him a second shot at a chance that he thought he had lost.

Sugihara helped pave the way for Asian-Americans in science and made advancements in chemistry. Now in his late-90s, there’s not much work left for him professionally. Sugihara has been enjoying retirement, spending summers in North Dakota and winters in Arizona.

c.macdonald@dailyutahchronicle.com