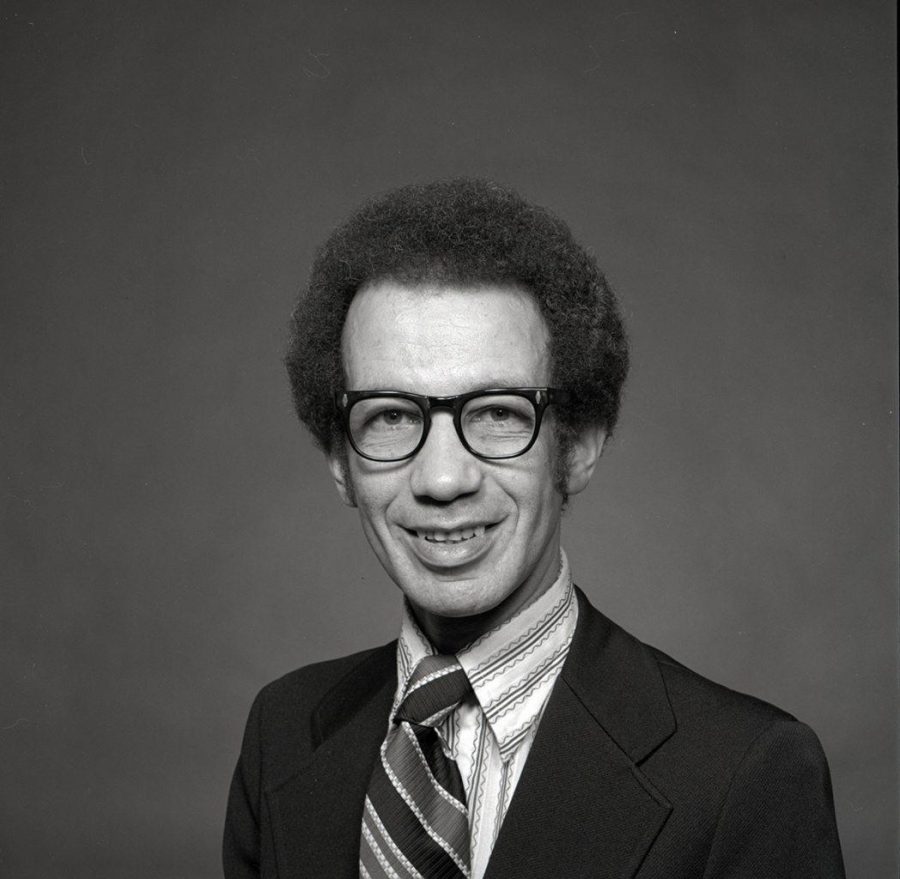

Nearly 25 years after his death, the work done by Charles Nabors, the first black faculty member at the University of Utah and civil rights activist, continues to open opportunities for students.

Nabors was hired as a faculty member in 1958, and he later received his doctorate degree from the U in 1965. He was officially awarded tenure in 1972 as a professor in the anatomy department.

Nabors was known for his dedication to helping students, particularly those who were part of underrepresented groups in the health sciences elds. He was appointed the assistant dean for Minority Affairs in the U’s medical school in 1976, and he worked throughout his career to raise awareness of racial discrimina- tion and injustice he felt was invisible to the community as a whole.

In addition to his academic efforts, Na- bors was politically active on both a local and national level. In 1968, he was a delegate at the Democratic National Convention, serv- ing on the Committee on Credentials. Nabors was involved in George McGovern’s political campaign against Richard Nixon in the 1972 presidential election.

Nabors’s participation in politics frequently took him away from home and led him to spend a lot of time on the streets to achieve his goals. He ran numerous political organiza- tions and raised money for Democratic candi- dates. Nabors was passionate about the issues and theory behind politics, but he did not care for the mudslinging and drama associated with partisanship.

“By theory, I mean de ning issues, talking to people about concepts, those kinds of things — ideology and tactics behind political move- ments,” Nabors explained in an interview with Leslie Kelen on March 2, 1984.

Nabors cared most about civil rights for people of color and the many struggles blacks confront that are not publicly recognized.

He also held a vested interest in the plight of low-income individuals and felt strongly about striving for economic equality.

In 1968, Nabors served as a member of the Utah Citizens for Kennedy Committee, in which he helped to organize Robert Kennedy’s trip to Utah during the 1968 Democratic presidential primary. He always managed to keep a foot in the door politically to help facilitate what he thought was right for society.

Nabors also worked with the NAACP’s Salt Lake City chapter to eradicate racial discrimination.

Born in 1934 in Cleveland, Ohio, Nabors came to the U for his education. He was married and had three children. Nabors dealt with a number of complications in his personal life, includ- ing two babies who were born prematurely at separate times and passed away not long after birth. Nabors and his wife worried about hav- ing to go through the death of a child again, so they chose to adopt two of their three children.

In his interview with Kelen, Nabors said he was driven by two main goals.

“To succeed, number one, professionally, to succeed in that good old American measure — the size of one’s bank account, and to succeed as a parent and family person,” he said.

Nabors achieved both of these goals, though when his kids were young he occasionally wor- ried about not being involved enough as a fa- ther. He was busy and dedicated a lot of time to his career as a professor as well as to his politi- cal and social efforts. In his older age, however, he felt as though he was able to step into more of a fatherly role and ful ll the responsibilities of a parent.

“Those are important things. Life would be pretty dull if you had simply one ambition,” Nabors said. “It would be dreadfully dull.”

c.macdonald@dailyutahchronicle.com

@TheChrony