No time to read? Check out this story’s episode of the Floodlights podcast: http://kuteradio.org/talkshows/olympic-legacy/

Some have called the 2002 Winter Olympics one of the most successful in the events’ long history — boasting the most funding with the least number of sponsors — even amid bribery scandals. The 2002 Games brought significant infrastructure improvements to the city as a justification for construction of the TRAX system and sporting venues. Utah has hosted over 60 world championships in a variety of winter sports using those facilities. As one of the few Olympic host cities to have actively maintained its venues, Salt Lake City has recently expressed interest in bidding for the 2030 Winter Olympics. Although officials argue that Utah’s still functional venues make the state an ideal candidate, the legacy of the 2002 games has been neglected in some ways — especially by Salt Lake City.

The Hoberman Arch

The heart of the 2002 Olympic Games beat in downtown Salt Lake City, where many relics of the games have been removed from public streets, including monuments along Main Street. The most publicized neglect is perhaps that of the Hoberman Arch, a mechanical sculpture designed by Chuck Hoberman which served as a sort of curtain for the medals stage in 2002. The arch’s movement is often compared to the iris of an eye — the center circle of the arch would expand to reveal the podium.

Almost immediately after the 2002 games, city administrators and Olympic organizers couldn’t agree where to put the arch. Several proposals were made, including an Olympic Legacy Park commissioned by then-mayor Rocky Anderson. He drew inspiration from the success of Atlanta’s Centennial Olympic Park, with its interactive Olympic Ring fountain, sculptures and ferris wheel.

Olympic parks are often controversial, but Anderson felt Salt Lake City had the means to succeed. He wanted the Hoberman Arch to be installed in Pioneer Park — chosen after consideration of 13 other sites — alongside other Olympic memory items. Planners intended to use the arch as part of a stage for a concert venue, similar to the way it was implemented at the Olympic Medals Plaza during the Games when artists such as the Dave Matthews Band, Smash Mouth and ‘N Sync performed in front of it.

“During winter, [the park] would have an Olympic size ice skating rink with all of the flags of the nations around it. It would be all lit up at night with music and a little café,” said Anderson. “In summer, we wanted to have moveable tables, chairs and kiosks, and a historic garden just to make a place where people could come socialize, get a little food and just enjoy our Olympic Legacy. It would have made Pioneer Park a much safer place, and would have attracted people from all around the area.”

Proposal Roadblocks

Anderson said Fraser Bullock, a leader of the Salt Lake Organizing Committee (SLOC), had agreed to the proposal and granted $7 million to the city to begin construction. But some city officials and residents raised complaints. Opponents of the plan claimed it violated policies regarding open space on city property and had concerns about the possibility of the new venue overshadowing the history and heritage of Pioneer Park. The possibility of displacing the homeless population was also raised. The Pioneer Park plans were subsequently abandoned.

Not long after, the SLOC proposed construction of the legacy park at the Gallivan Center, according to former City Councilman Carlton Christensen.

“We felt like if it were at Gallivan it would be highly accessible for folks staying in hotels or going to other venues around there,” Christensen said in a telephone interview. “[It] was a little easier for them to get to.”

However, there were also significant issues with the Gallivan Center. The International Olympic Committee has tight sponsorship agreements and, although it didn’t have any Olympic markings, the Hoberman Arch is closely associated with the 2002 Games and served as a symbol of the IOC. Many of the events held at the Gallivan Center have corporate sponsors that aren’t associated with the Olympics and their logos are often displayed within the Plaza. The IOC rejected the Gallivan Center proposal because of the potential for breach of their sponsorship agreements.

“By that point, the organizing committee was … turning out the lights and shutting down their offices,” Christensen said, because the Olympics were long over and their obligations were ending. “Government is seldom fast, and Salt Lake City government is often even a bit slower than most … We just weren’t in the decision-making mode fast enough.”

After the Gallivan Center idea was shut down, Fraser Bullock and the SLOC coordinated a final effort to get the arch installed at the University of Utah — this time successfully. It would be one of the last things the SLOC did.

Legacy at Rice-Eccles

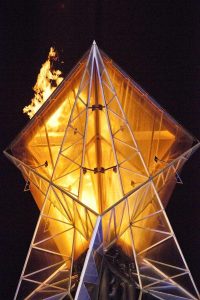

The U agreed to house the arch for six years, with the contract ending in 2009. The arch was erected at Rice-Eccles Stadium — the site of the 2002 opening and closing ceremonies — and integrated into the Olympic Cauldron Park alongside the Olympic Cauldron and a small visitor center. It stayed from 2003 until 2014 — five years after the U’s contract expired.

Stadium officials said they would have been happy to keep the arch, but felt it would be better suited for another location amid renovations to the south end zone. The first phase of the Two_Phase Stadium Plan for renovations, completed before the 2014 football season, included reducing the “physical footprint of the current Olympic Park” by removing Hoberman Arch, moving the Olympic Visitor Center memorabilia to the Park City Olympic Legacy Park, and converting the visitor center space into a recruiting and reception area. Phase two of the renovations is still in progress but involves shifting the position of the cauldron.

“That [shift] won’t happen until we decide what we are going to do with the south end,” said Aaron White, the interim director of Rice-Eccles Stadium. “There is a feasibility study out now that’s discussing what the finances would be for that.”

According to Gordon Wilson, associate vice president of Auxiliary Services at the U, there are extensive renovation plans being made for the south end.

“The scoreboard came up first, so we went ahead and placed that, but when you think about placing something that big, you start to look at all of your space,” Wilson said. “We started looking at our south end building, which is 40 to 50 years old, and deteriorating fast.”

Despite that, the cauldron will stay at the U. There has been speculation that it is no longer functional because it is rarely lit during the Olympics or other events, as is sometimes done in other host cities. According to White, the cauldron does run but it requires significant funds to light, and doing so can damage it. Much of the cost comes from hiring an engineer to oversee the lighting in order to minimize that damage.

“The mechanics of lighting the cauldron are … complicated,” Wilson said. “The fire travels up the cauldron, while cool water flows down. That rapid heating and cooling can warp the glass.”

Both White and Wilson say U administrators feel keeping the cauldron intact for visitors to see is far more important than frequently lighting it, and agree that the cauldron is a huge consideration in the renovation plans. They don’t want to bury the remaining Olympic legacy at the stadium behind the new additions. The most likely option, according to White and Wilson, is to move the cauldron out of the way of game festivities, where it can be given its own space.

“If and when we redo the end zone, we want to find the perfect place for the cauldron,” Wilson said. “We feel it is a part of the Olympic history that needs to stay right here at the U.”

More than anything, White said the U — in coordination with the Utah Olympic Legacy Foundation (UOLF) — pursued the relocation of artifacts like the arch in order to give Utah’s Olympic legacy the public exposure it deserves.

“There was a big drop off in the number of people that were coming to see it here, and most people were bypassing it [to take] pictures of the cauldron,” White said. “In our conversations with the Olympic Legacy Foundation, both of us thought that the assets would be better served where more people could see them and appreciate them in person.”

But that’s not what happened.

Transferring Ownership

UOLF declined to house the Hoberman Arch after its stay at the U because of the cost associated with construction and maintenance, according to Alf Engen Ski Museum director Connie Nelson. Nearly every party privy to the relocation efforts expressed concern regarding those costs. Christensen said the city council dealt with similar issues.

“The Hoberman arch was a very intensive mechanical piece of equipment,” Christensen said. “While we had some conversation about [how you could] maintain [the] mechanical nature of it opening and closing, it was a little problematic in that the thing really wasn’t designed for day to day operation but for use during the days of the games. So the likelihood of really keeping it operational on a long-term basis was not [high].”

Neither Hoberman or any of his engineers could be reached for comment on the details of the arch relocation.

At the U, the mechanical issues were avoided by installing the arch as a stagnant piece of artwork and not allowing it to be extended at all, something administrators felt diminished the interest of the structure.

“It was good for us [that the city offered to take it], because we want to keep these kinds of things around,” Wilson said. “We felt like we were good stewards of Olympic memorabilia. We stay really close with the Olympic Legacy Group … we both want to see these things taken care of.”

White said that, with the dip in visitation numbers, it made more economic sense to remove the arch from its place near Rice-Eccles and make the space available for use by the U. The administration of Anderson’s successor, then-Mayor Ralph Becker, immediately expressed interest in placing the arch within city boundaries, with ideas for parks or potential incorporation into the new airport, according to White.

The arch was dismantled and returned to Salt Lake City’s possession in August 2014. It doesn’t seem, however, that the city had the same dreams of increased exposure of the Olympic legacy the U did in the decision to relocate the arch.

In a Salt Lake Tribune article at the time of the arch’s removal, Becker’s administration claimed they received no notice of the arch coming under their ownership. However, several university departments have copies of an April 2014 letter from David Everitt, Becker’s chief of staff, stating the city agreed to take the structure. The letter claimed the city had plans to install the arch by the end of 2015 “subsequent to the Mayor’s approval.” However, the city could provide no record of discussion surrounding the Hoberman Arch during the Becker administration. Instead, the arch was placed in an outdoor impound lot and waited for plans to be made.

Loading...

Loading...

Missing Pieces

Salt Lake City’s goal to install the arch by the end of 2015 was never reached because, in December 2014, 29 pieces of it were stolen as it sat in the lot. Many officials believe the pieces were likely sold for scrap, or recycled for the aluminum. The perpetrators were never caught, leaving the city with a partial arch and compounding the financial burden of finding a home for the structure.

It cost the city $116,000 to deconstruct the arch and move it from the U into storage — a financial hit that likely impacted the Becker administration’s ability to put resources into researching locations and, later, refabricating the missing pieces.

A former member of Becker’s administration who wished to remain anonymous said in a call with The Chronicle that “the short answer is probably that [they] entered into the messy 2015 race for re-election and everything got put on hold.” The administration member continued, “Once Becker was out of office, the public services director was fired by the new mayor, [and] everything got a little delayed and disorganized.”

That “new mayor” was current Mayor Jackie Biskupski who, alongside many candidates in the 2015 mayoral race, made promises to find a permanent home for the arch. In 2016, Biskupski spokesman Matthew Rojas was quoted by the media saying the missing pieces were being remanufactured, and the mayor’s office was “committed” to finding a place for the Hoberman Arch.

Lia Summers, Biskupski’s advisor for Art and Culture, contradicted that statement in an interview with The Chronicle this year. She said the remanufacture of the pieces is still in the research phase.

“It’s made of a translucent kind of aluminum, so [remanufacturing] involves understanding exactly which process the artist used originally to refabricate,” Summers said.

The mayor’s office has yet to contact artist Chuck Hoberman for consultation on the remanufacture process because, according to Summers, they are still trying to find an “appropriate location.”

“Everything else can be done relatively easily, but finding the right location is something that the mayor is really interested in taking a thoughtful look at,” Summers said. “We want to find somewhere that will allow it to be secure, visible and of course won’t pose any public safety issues — in the past, people have climbed on it.”

Uncertain Future

Despite two years in office, the Biskupski administration’s research into how to best display the arch still has not turned up any location proposals. One reason for the delay could be a restructuring of the city’s bureaucracy.

According to Summers, the city’s first priority has been working on developing a sustainable distribution process for Salt Lake City’s public art funding budget under a new art department created by Biskupski — she did so in an effort to give arts projects more resources to draw from.

Figuring out how the art division was going to function under this new structure caused some delays in the Hoberman project, according to Summers. She said it took the administration about a year and a half after taking office to get all departments settled.

The city is also searching for funding to re-erect the arch. Summers said the funding would likely have to be a combination of state arts funds and chunks of the city budget. No funds have yet been set aside for this project, and Summers did not know of any funds from the Becker administration or the public art program in place for the project in previous years.

Biskupski herself has been heavily involved in research conducted by the Olympic Exploratory Committee surrounding the recommendation for a 2030 bid to bring the Olympics back to Salt Lake City. The arch is not mentioned in the committee’s bid recommendation report, but Summers said that relocation of the arch will continue to be researched regardless of its involvement in possible 2030 venues.

The Hoberman Arch still sits in disrepair today, now in a secure storage space. Salt Lake City declined to allow The Chronicle access to it.

“In order to keep the Arch safe and secure until it is in a new space with a new safety/security protocol in place, it would be best to not allow external visits to its location,” Summers said.

Anderson and others with close ties to the 2002 games are deeply disappointed that the arch has been neglected, and that so few people have been able to enjoy it. Anderson, in particular, has been very vocal about his thoughts that the Olympic Legacy is not cherished by Salt Lake City in the way it deserves.

The city’s apathy toward Olympic relics raises some speculation among the community whether Salt Lake City would handle the legacy of the 2030 Winter Games more gracefully, if it were to host the Olympics again.

m.hulse@dailyutahchronicle.com

@megshulse