In 2014, the viral mobile game Flappy Bird was suddenly taken off Apple’s App Store by its creator. Intended only to be played casually, the creator had accidentally implemented what he considered “addictive” mechanics in the game’s design and therefore felt morally obligated to remove it from the store when it exploded in popularity.

Generally, social media isn’t described as a game, but product designers at large technology companies are definitely designing platforms to work as such. When creating social media platforms, the ultimate success of the platform is measured by how much of a user’s total attention can be captured. This measure comes from the concept of the attention economy, an economic theory that treats human attention as a scarce resource. Attention is perhaps most important to platforms that use an advertising model as its revenue stream since the amount of revenue generated by these particular platforms directly relates to the amount of viewership it can offer to its advertising partners. To gain our attention and keep it, technology companies use gamification. Gamification is a term formally described as the application of game design into non-game contexts. Essentially, technology companies use well-known game design principles to take advantage of commonly held human desires to socialize, be competitive, complete achievements or attain status in order to “gamify” our social media lives. And while gamification can be a useful tool when used to enhance activities related to health, education and work, to gamify our social lives and relationships comes as a detriment to the consumers involved.

Last year in an interview with Axios, Sean Parker, the first president of Facebook, said:

“The thought process was, ‘How do we consume as much of your time and conscious attention as possible?’, which meant [Facebook] needed to sort of give you a little dopamine hit every once in a while because someone liked or commented on a photo or a post or whichever is going to get you to contribute more content. . . . It’s a social validation feedback loop. . . . You’re exploiting a vulnerability in human psychology. . . . [Everyone at Facebook] understood this consciously, and we did it anyway.”

He later said in the interview, “God only knows what it’s doing to our children’s brains.”

Natasha Schüll, cultural anthropology associate professor at New York University, and the author of Addiction by Design, stated in an interview with The Guardian that technology companies such as Facebook and Twitter use many methods to keep you constantly engaged with the platform. One such method she describes are “ludic loops.” These involve cycles of uncertainty, anticipation and feedback “designed to lock users into a cycle of addiction, . . . a function of continuous consumer attention, which is measured in clicks and time spent.”

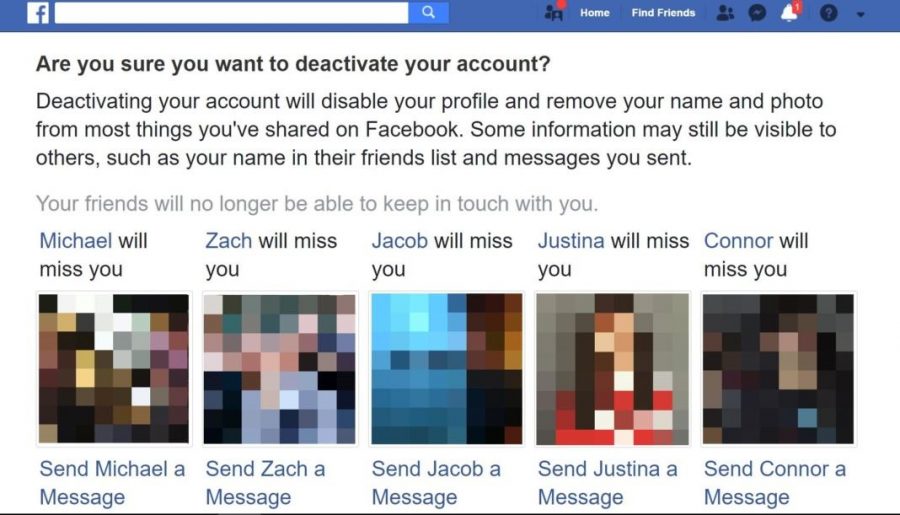

Last year when I deleted my Facebook account, I remember the site showing me a photo gallery of my friends and family with captions saying, “[So and so] will miss you.” The reason I chose to delete my Facebook account in the first place was because of the increased spamming of “user retention” emails that flooded my inbox due to my inactivity, and my inactivity was due to my exhaustion at being flooded with “junk food” whenever I went on the actual platform. Social validation (such as popularity metrics), guilt (such as SnapChat streaks), fomo (such as retention notifications) and the inundating of users with content are just some of the techniques social media engines use to habitually train and condition us into constantly participating. Unfortunately, socializing with others online is how many of us stay connected to society and our peer groups. How we reconcile ourselves with the fact that our main line of socialization has been commercially hijacked will define social media in the future.

Though many Silicon Valley insiders have come forward to blow the whistle on the techniques social media companies have used to exploited human psychology with addictive mechanisms, lawmakers and consumers still seem either completely unaware of such revelations or are unconvinced by them. Inaction towards the issue is perhaps due to the fact that the controversy has been completely overshadowed by another social media related scandal that erupted this year regarding the revelations that the Russian state had created vast bot networks and mock news organizations to disseminate false information about the 2016 presidential election. The discovery that Cambridge Analytica had been collecting data through Facebook’s unregulated user data API to target voter’s psychological fears as a means to advertise presidential candidates has also taken over the spotlight. Nonetheless, the scandals of this year have taken the once widely held perception that Silicon Valley is full of “socially responsible” and “progressive” people and shifted it toward resentment and distrust. Hopefully this shattered trust in Silicon Valley ultimately proves to be the needed catalyst to reform social media towards a more transparent and less addictive means of socialization.