Many people believe in at least one conspiracy theory. There are plenty to go around, from innocuous oddities to insensitive denials. The “conspiracy theory” is an amorphous term that covers the gamut of counter-culture beliefs. They preach that celebrities are killed and replaced by clones, that socio-political aspects of life are controlled by the Illuminati or that, perhaps, the Holocaust just never happened. Even the belief that President Trump might have colluded with Russian adversaries to ensure his electoral victory remains a conspiracy theory — though for what it’s worth, Watergate, too, was once considered only a theory.

Modern society should know better than to invest too heavily into such intrigues, yet these weird, dark narratives thrive like only a thousand-headed hydra could. They are the inescapable product of natural human suspicion, an innate hyper-awareness toward anything that smells of secrecy or subterfuge. It wouldn’t be fair to write that instinct off as completely irrational. Many theories have uncovered devastating betrayals by people and institutions with consequential power. It would be foolish to put complete, blind trust into any institution — corruption is everywhere. On a functional level, the creation of conspiracy theories is a predictable reaction to the treatment that many communities have experienced in the past. Yet it feels as if we have put a disproportionate amount of legitimacy on the claims conspiracies make but never get close to proving.

As someone who has been profoundly harmed by a proximity to such theories, I try to keep in mind the human rationalization behind believing them. My attempt to understand the bizarre comfort that some people take from believing that the government is spraying chemicals from commercial jets or drugging their water has been a crucial part of my healing process. As twisted as it sounds, people do get a sort of comfort from this intellectual poison of choice. They consider themselves privy to special information, and therefore prepared for the worst-case scenario. No clandestine horror has evaded their research and preparation.

In my case, I grew up with first-hand experience of the internal spiral that these theories construct. The worldview I was raised in was glutted with intensity. I was taught to avoid computer webcams, fingerprint scanners and the facial recognition tagging features on Facebook, all to avoid spying from “the government.” Watching music videos was risky business, as practically all mainstream artists were believed to participate in rituals, be possessed by demons or push mind control on anyone who watched their visual work.

Whether it is feminism or fluoride, every societal ill has some disjointed, “actual” cause according to conspiracy theories. Anti-depressants lead to school shootings, the government is “making” global warming, every high profile death is actually a covert assassination. Without getting too mired in details, the anxiety-producing effect of these theories intensified when I, a teenager, was informed that the end of the world would be within five years. When looking back on why I didn’t perform as well in the schoolwork necessary to build a future, it’s clear that it was because I would numbly sit in my high school cafeteria, trying to estimate how many of my peers would soon be dead.

The perpetuation of conspiracy theories is not a victimless crime. For every theory that is proven true, a disappointing majority remain shaky at best. Despite being unable to bear the burden of truth, their corrosive quality harms the communities around them. An unhealthily suspicious worldview breeds anxiety, encourages “othering” and harms victims. It doesn’t matter how well-intentioned their peddlers might be.

Conspiracy theories aren’t just “ideas.” People should pause before treating conspiracies as interchangeable with any other currency in the ideological marketplace. They are fundamentally extreme claims that carry the weight of implication. They should prove their veracity before expecting acceptance. There is no seat at the table owed to any idea, especially not just because they play the devil’s advocate. When the crux of so many theories depends on the existence of a corrupt state with a long-term plan for subtle genocide, they are going to need to shoulder the burden of proof.

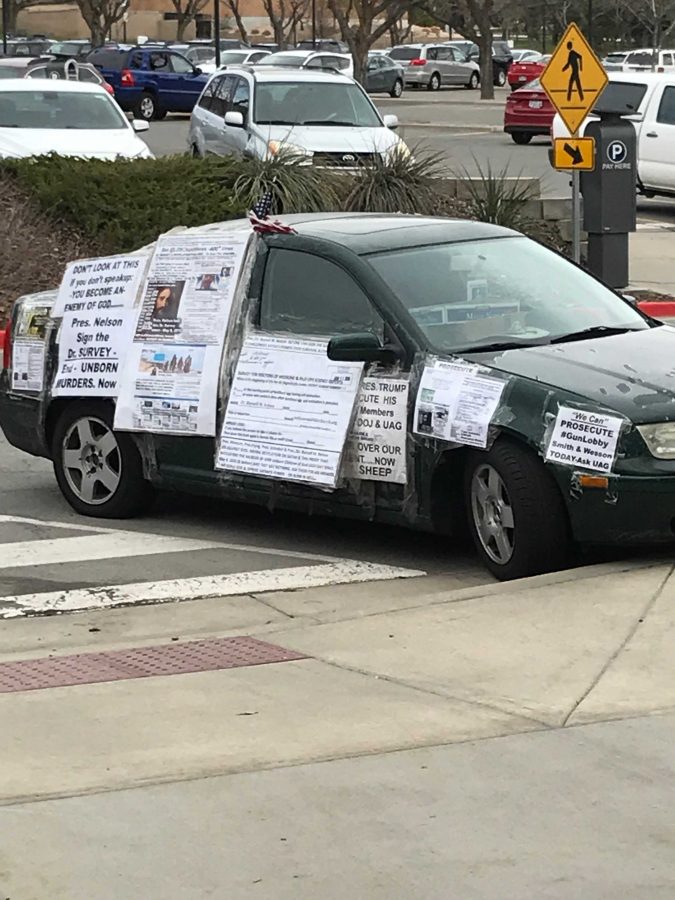

Not all conspiracy theories are created alike, but they all feed into maladaptive processes. Conspiracy theories can create monsters within our own backyards, whether by projecting their shadows across our minds or by turning us into them ourselves. Like a flesh-eating disease, the fear stoked by these lurid, sordid scams breaks the mental epidermis, rotting people away with anxieties that may not be based in reality. Vulnerable people become consumed as they are rattled — or worse, radicalized — within their own basements.

It might sound extreme to tie these ideas — the infamously fallacious, eccentric debris of the internet — to social violence. Sure, people might be swayed by the political memes and the clips of Infowars they might glean from social media, but are they truly radicalized? Yes, extreme viewpoints might polarize people and encourage them to bully or dox their opposition, but is that actually violence? The unwillingness to ask these hard questions falls flat. In an effort to appear moderate and balanced, people protect these ideas more than they should.

That’s all good and well until the human cost begins to rack up. The most popular conspiracy theories of the moment empower racist, far-right paranoia, stoking anger and bad behavior. They enable violent people to use their aggression as a sort of personal crusade. Society reaps what it sows by offering this ideology a platform.

One such fruit is the dogged conspiracy theorists who devote their resources to taking down the victims of tragedies. It doesn’t matter what they have already survived; if they disrupt a preferred narrative, they become a target. Victims of mass shootings are hounded, called “crisis actors,” sent threats and deprived of the privacy of their information. Conspiracy theorists paint the teenagers who survived the deadly Parkland massacre as manipulative government plants. They harass the parents of the murdered Sandy Hook kids, howling that their murdered children never existed in the first place. Conspiracy chokes compassion.

Another fruit is the stoking of anger and the turn to violence spurred by conspiracy theories. This is clear from Pizzagate, where a gun wielding “self-investigator,” who believed occult Democratic politicians were using a pizza parlor to traffic children, showed up to settle the score like a guns-a-blazing vigilante. Another young man was radicalized by the same far-right conspiracies and eventually exploded in rage, stabbing his “liberal pedophile cuck” father to death in their home. Both young men fancied themselves heroes of these non-existent children, their actions valorized by what they considered a heightened awareness of the situation. It’s an understatement to say that these theories only play with fire — they openly pour gasoline on the flames.

Unfortunately, our modern resources give conspiracy theories enormous reach. Technology has skyrocketed over the last several decades and has left many people behind to dwindle in media illiteracy. When people conceal their identity or adopt that of a charismatic, credible champion, technology lends them the power of the whistleblower. When data can be collected, edited, manipulated and distributed with mere mouse clicks, shouting into the void might produce quite the return on investment. People will find the content and communities they are looking for, no matter how socially destructive they might be. All human tools are double-edged. Connection is no exception.

There is no place for such toxic misinformation in a healthy society and people ought to take it upon themselves to ensure that it is not being spread within their circle of influence. Free speech can still be maintained without offering extremist conspiracy theories a platform. Enabling such behavior, even in the spirit of open debate and exchange of ideas, is short-sighted and immoral.