Zines (pronounced zeens) are a form of alternative press, short for fanzine. They typically take the form of small booklets that have drawings, poems, stories or essays that are then photocopied and distributed.

The first zines can be traced back over 200 years to publications such as Thomas Paine’s “Common Sense.” Arguably, the practice of independently publishing creative and political works similar to a zine is even older. Consider figures throughout history who wrote and distributed their own views, such as Martin Luther with his 95 Theses.

The independent press movement really took off in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Pulp science fiction publications that began during the Great Depression are where the modern zine format truly comes from. Hugo Gernsback published the first science fiction magazine, Amazing Stories, in 1926, which had a letter section where reader’s addresses were published. Readers of the magazine began to write to each other and produce the first true fanzines. The fanzines would include anything from short stories to fanfiction. Fanzines were a way for people to connect over shared interests and share their own personal perspective.

Zines began to evolve as science fiction fans discovered they had other shared interests. Finding someone with a shared passion is exciting, but finding someone who shares multiple interests with you is special. We still see this phenomenon of self-segregation within a fandom today. For example, fans of the podcast “My Favorite Murder,” called murderinos, can find a murderino subgroup on Facebook for almost any topic.

The self-segregation of fan groups is began to occur during the 60s. Science fiction fans began connecting over other passions, especially rock and roll. This time period established the deep connection between zines and independent music that still exist today. Around the late 1970s, the punk subculture found their place in zines.

People also had more access to printers and photocopiers in the late 70s, making it much easier to create, copy and distribute zines. In the US and the UK, zines became an important way for counterculture to spread ideas from city to city. Most zine creators would include an address of PO box on the last page of their zine. You would send your information and maybe a dollar or two to the address and you would get the next issue of the zine sent back to you.

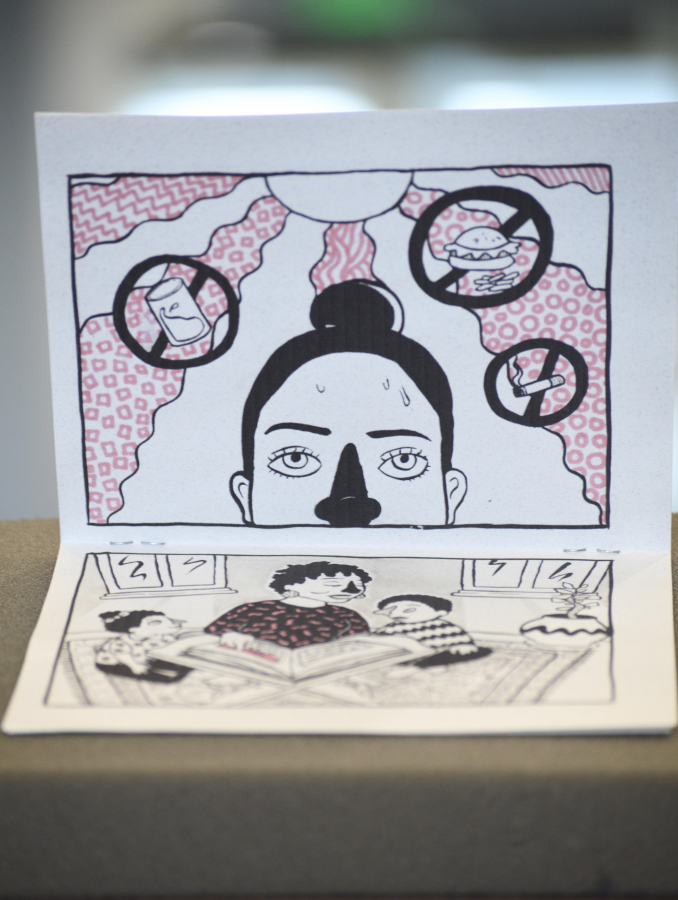

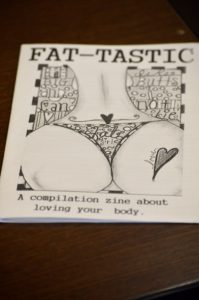

Counterculture has always been a place for members of marginalized groups to connect and zines allowed those people to have a voice. Historically, zines were a place where equality and discrimination could be discussed. Zines became a place to discuss race, sexual orientation and class issues. In the 90s, they worked in tandem with the DIY punk subculture as a rallying cry for third-wave feminism. There’s a long history of women using self-publication methods such as scrapbooking to circulate ideas. Zines became just another method to challenge concepts related to sexuality, gender norms, body image and violence.

Like most printed media, the Internet has affected the publication of zines, but it hasn’t killed the art just yet. The internet has become a place to share ideas, opinions and creativity, much in the same way zines were. However, thoughts put out on the internet can get lost in the oppressive void. Zines still have an appeal for creators — they are more personal than a Tumblr blog and aren’t subject to the same scrutiny as a tweet. You can’t leave a comment on a zine. Instead of disappearing in the age of the internet, zines have simply adapted.

Today, you can find zines being sold on personal websites and Etsy. Zines are also still sold and distributed through independent shops and libraries. The J. Willard Marriott Library keeps zines in their special collections and the Salt Lake City Public Library system has one of the largest collections of zines in the country. Salt Lake City Public Library also hosts Alt Press Fest every year. Alt Press Fest 2018 is on Oct. 13 at the Salt Lake City Public Library’s main branch downtown.