The American birth rate has been falling over the past decade. The latest U.S. Census population estimates indicate that fertility rates are down and hit a record low for a second year running in 2017. Many people are trying to make sense of this trend, including Robin E. Jensen, professor of communications at the University of Utah.

Jensen is particularly interested in understanding how the public conceptualizes fertility and states that “Once you understand those perceptions, then it might be possible to contextualize shifts in fertility rates over time.”

In a recent study published in Archives of Sexual Behavior, Jensen and colleagues surveyed 990 U.S. adults and asked them the following questions:

- At what age does a female first become fertile?

- At what age does a female reach peak fertility? That is, when is she most fertile?

- At what age is a female no longer fertile?

- In general, what is the ideal (or best) age for a female to get pregnant for the first time?

- In general, when is it too late for a female to get pregnant?

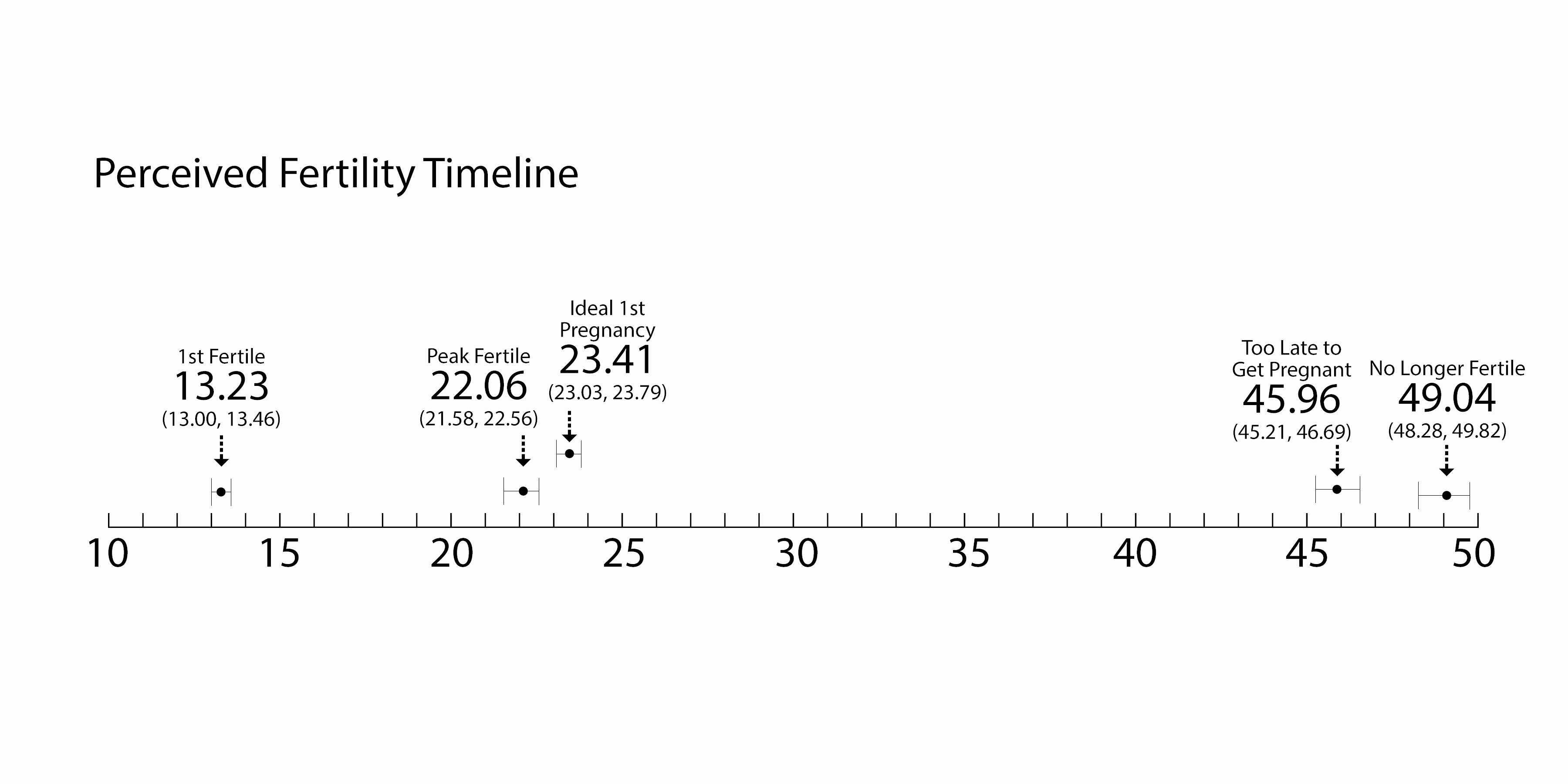

A human fertility timeline developed from the survey responses shows how U.S. adults perceive fertility to manifest and shift across time.

Study results indicate that peak fertility is perceived to be around age 22, closely followed by the ideal first pregnancy around age 23. According to Jensen “there seems to be sustained support for peak fertility falling between 19 and 27.”

Grace Mason is a sophomore majoring in political science and health society and policy, and is the president of the Campus Contraceptive Initiative at the U. In response to the research, Mason states that “I think that saying there is an ideal time to get pregnant puts a lot of stress on women, especially in college.”

According to Mason, “If we focus only on the scientific determination, we might not understand how the previous history of paternalistic medicine told women about when and how they can have their pregnancy.”

“Indeed, the decision of when (or if) to have children is deeply personal and influenced by numerous factors, some of which — it is important to note — are entirely outside of individual control,” Jensen said in an article on the College of Humanities website.

Biomedical Engineering graduate Roxy Julian adds “We don’t live in a world where peak fertility depends just on the biology of the person, because of technological advances, and the social and economic advances that make those advances accessible to different people.”

Fertility perceptions varied among groups based on factors including income level, ethnic identity and risk for health disparities. Naveen Rathi, a first-year medical student at the U, states, “I think the discussion on health disparities between those of different income levels speaks volumes. It shows that these types of disparities still exist that we may not think of in different portions of the population. It speaks to the importance of family planning services and health literacy and education.”

“We see the fertility rate declining because women are able to choose when and how they want to start their families,” Mason said, “rather than have societal norms forced upon them saying that ‘you need to have children now because this is when you are most fertile’.”