Women in resource-poor countries have limited access to feminine hygiene products, according to a 2017 study published by the National Institutes of Health. Most women in these countries turn to old cloths, tissue paper, cotton or wool pieces, or some combination of these items to manage their menstrual bleeding. When commercial menstrual products are available, however, they often contribute to high pollution levels. One University of Utah student has been working toward a solution to this problem for the last three years.

Amber Barron recently received a $3,000 grant to continue production on a biodegradable adhesive for a maxi pad. The grant, offered through the Lassonde Entrepreneur Institute’s Get Seeded pitching competition and sponsored by Zions Bank, offers monthly milestone funding for student entrepreneurial projects.

Research for the biodegradable pad began in 2016 when Barron was a freshman in the materials science and engineering program. Now a senior, Barron said the product is nearly ready to enter the market.

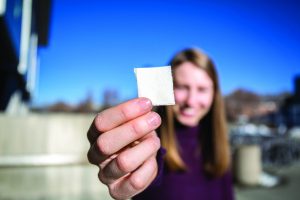

“Everything comes down to the materials that you are using,” Barron said, holding up two swatches of biodegradable adhesives, which she said are in the last stages of testing in order to begin full-scale manufacturing.

Sustainable Hygiene Engineering Research and Operation (SHERO) was formed as a startup to create the pad after former team member and U student Alicia Dibble won the Get Seeded grant in 2017. Barron has been the sole member of the team responsible for engineering the adhesive for the product. According to Barron, the adhesive is one of the most important parts of her pad as it sets the pad apart from other feminine pad options that claim to be biodegradable but use adhesives that are not.

There is currently no biodegradable adhesive on the market that can be applied in the hot molten state — necessary in order to create pads, diapers and other similar products. Barron explained that the adhesives she has been testing are 100 percent biodegradable.

“If the adhesive fails, then the product fails catastrophically and people might not want to use it,” Barron said, adding that she is taking care to ensure that the product will have a “good shelf life and that it is not going to leak during use.”

Barron said it has been hard at times to balance her classes with work on the product. Many of her past efforts were focused on applying for and acquiring grants that would help with production. Among these are the Cleantech Open National Consumer Choice Award in 2017 and the Bench to Bedside Consumer Choice Award. Now that she is in her senior year, Barron said that she has more time to focus on the research and development of the adhesive, putting in about 10-20 hours of work per week.

Barron credits her success to the materials science and engineering program at the U. She said she always knew that she wanted to do something with sustainability but had “never thought of it as a career” until her enrollment in the program. The program “really kick-started” her career because it allowed her “the chance to be in a place where professors know your name,” Barron said.

It was because of this familiarity that Jeff Bates, a U professor in the program, approached Barron about researching a biodegradable absorbent material back in 2016. Bates told her that he thought she would be “interested in women’s health as well as biodegradable materials.”

The research team was originally given the task of developing a comfortable and absorbent material for a biodegradable menstruation pad to be produced as a humanitarian project for SHEVA, a non-profit in Guatemala. Once the team developed the material, they offered to produce the full product and founded SHERO in order to do so. Barron said that throughout the process the team remained “student-focused” with the independence to test numerous formulations of the various materials.

SHERO hopes to create partnerships with NGOs in order to provide sustainable sanitary pads at reduced or no cost to women who could not otherwise afford them. Barron said that “in addition to the humanitarian aspect of it, we really are trying to get [the pad] to where it is the standard for feminine care.”

“The average person is throwing away pounds of trash every day here in the U.S. If we can cut any part of that, then we should choose to do so,” Barron said. She added that the biodegradable pad is important because “over the course of a lifetime, women of menstruating age are constantly using non-biodegradable pads that end up in landfills and do not degrade in our lifetime.”

Barron said that SHERO is working with a number of organizations to help end period poverty in resource-poor countries. In addition to providing pads to women in these areas, SHERO hopes to create jobs by working with partners to teach women how to operate pad production facilities.