Edwards: Want to Improve Presidential Elections? Make the Debates Less Entertaining

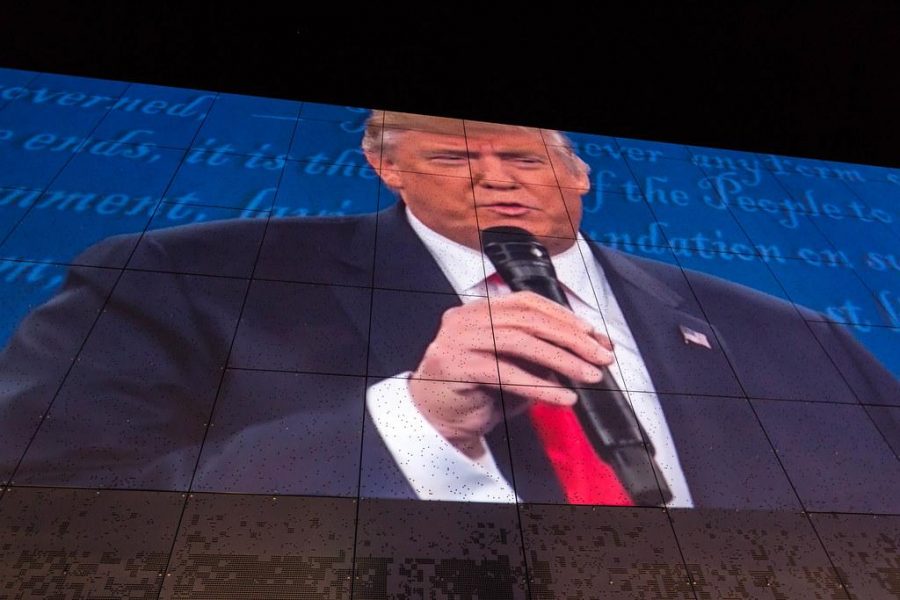

Donald Trump’s image is projected on the side wall of Public Media Commons in St. Louis during the second presidential debate watch party. (Courtesy Flickr)

July 2, 2019

The dynamics of the 2016 general election are best summarized with an excerpt of a CNN article from September of 2016: “Trump dismissed Clinton’s foreign policy record by accusing her of being ‘trigger happy and very unstable.'” Jennifer Palmieri, Clinton’s communications director, shot back at Trump in a statement that likened him to a “schoolyard bully who can’t rely on facts or issues.” The 2016 presidential election was dominated by personal attacks and misinformation. Virtually all discussion of policy was drowned out by quips about someone’s appearance, a pre-planned zinger about one candidate’s reputation or wisecracks about another’s family.

Because of the focus on personalities instead of policies, it’s no wonder that 58 percent of voters thought that the 2016 presidential campaign had not focused on important policy debates. This trend continued past the 2016 election and into the summer of 2019, with most Americans thinking that in recent years, political debate in the U.S. has become more negative and less respectful, fact-based and substantive. A majority has said that Donald Trump has changed political debate in the U.S. for the worse.

Despite the perceived increase in negativity, people remain interested and engaged in politics at record-breaking levels. During the midterm election season, there were historic levels of both small-dollar donations and voter turnout. In April 2019, polls indicated levels of enthusiasm around voting in 2020 similar to the levels documented close to election day 2016. The second Democratic primary debate followed the pattern seen in recent years of record-breaking debate ratings with over 18 million viewers, 3 million more than the Democratic primary debate in 2015. Glen Bolger, a partner at Public Opinion Strategies, recently said, “I think we are heading for a record presidential turnout at least in the modern era, and by that I mean since the franchise went to 18-year-olds” in the 1972 election.

If this trend continues, the 2020 presidential election debates are on track to becoming the highest viewed debates in history and have the potential to have a huge impact on the upcoming election. American voters clearly want to see a more civil political discourse, especially during elections, but there is no silver bullet that will prevent a repeat of the dynamic seen during the 2016 election with certainty. President Trump will continue the tweeting and name-calling, and the media will continue to cover his daily ravings. The only practical way to make the 2020 general election more respectful, fact-based and substantive is to change the way that the major party candidates will interact on the debate stage in 2020.

The best alternative to the typical format of two candidates standing at podiums moderated by a single cable news journalist is a combination of proposals by Bob Bordone, founder of the Harvard Law School Negotiation and Mediation Clinical Program and the Annenberg Public Policy Center. Bordone suggests a round table discussion of the topics most pertinent to the election, moderated by a group of print journalists, economists, historians, policy experts, university presidents or academic researchers. The round table discussion format will reward more civil interactions because of the close proximity and conversational nature, as seen in the third 2012 presidential debate. By allowing experts to moderate the discussion, moderators will be incentivized to ask questions focused on policy rather than questions to begin controversy, and candidates will be held accountable for inaccurate statements.

At the beginning of every debate, the moderator explains the rules and format of the debate, along with the disclaimer that the audience has been instructed to stay quiet. Unfortunately, this instruction is hardly ever followed, and throughout much of the 2016 presidential debates, audiences would shout, clap and laugh at remarks made by candidates. The removal of audiences from debates will disincentivize behavior similar to Trump’s infamous interaction with Senator Rubio — regarding the size of Trump’s hands — during one of the Republican debates. Because there will be no reaction from the audience, remarks like this will instead be met with awkward silence from the other candidates and moderator, as seen here.

Throughout all three general election debates in 2016, reactions from the audience muddied the interactions between the two candidates and — similar to a laugh track on a sitcom — prompted a reaction from viewers at home. Studies have shown that reactions from the audience alter a viewer’s interpretation of an exchange or the entire debate. By removing the audience from the presidential debate, answers become more about the content of the response than its performance.

Another aspect to improve is the split screen. “The split screen has been President Trump’s friend in these debates because he knows enough about television, that the producer will not be able to resist putting him on split with Senator Rubio if he’s making facial gestures,” said Dr. David Magleby, a retired Brigham Young University professor of political science, in a recent interview. This was true in both the primary debate of 2015 and general election debates of 2016. The use of a split screen divides the viewers’ attention between the speaking and listening candidates. It also incentivizes the listening candidate to make facial gestures and react to the speaking candidate, as seen in all of the presidential debates. And in addition to being distracting, the use of the split screen — which allows visible reactions from the listening candidate — can subtly affect the viewers’ perceptions of the candidates.

It is entirely possible to not use the split screen while broadcasting the debates, as it only became widely used as recently as 2004. In fact, all three full-length debates posted by NBC used a split screen, with Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton on a screen next to each other for almost the entirety of the debates. In contrast, the New York Times’ full-length livestreams of the debates never used a split screen and focused on the candidate that was speaking. While it may be more entertaining to watch one candidate make faces towards the other, it does a disservice to both candidates. Most detrimentally, the split screen rewards disrespect and discounts the value of the ideas being discussed.

Right now the presidential debates are designed in a way that prioritizes entertainment value over educational value, ultimately rewarding uncivil behavior. By changing the format of the 2020 presidential debates to a round table discussion moderated by experts, and removing live audiences and abandoning the use of the split screen, viewers will not only have a more informative and less contentious debate-watching experience, but will be able to evaluate candidates on their own terms, without the subliminal interference.