What to Do When Your Professor Goes AWOL

October 1, 2019

No time to read? Check out this story’s episode of the Floodlights podcast.

When University of Utah student Schyler Fox took an online History 1500 course last spring, it started like any other. Several weeks into the semester, however, her professor seemed to disappear.

“At the beginning of the semester, the teacher was really good,” Fox said. “The modules would be opened up in a timely manner for us to do it. And then he just fell off the face of the earth.”

In an online course, content is separated into modules, and the professor controls when each section is available for students to work on. This helps pace the students’ progress throughout the semester.

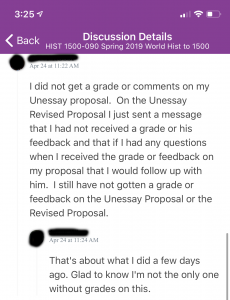

When students couldn’t progress any further, Fox’s classmates emailed the professor, asking him to unlock more assignments. She said they wouldn’t receive replies, but modules would open several days later. Students started their own discussion boards to ask whether or not other class members had their final projects approved by the professor, which was a required element of the course. Mid-semester came and went, and eventually, all response stopped.

With the semester halfway over, students “ended up having to go to the board of the history department and the head of history,” Fox said. They informed the administrators that “this guy’s gone.”

Once the history board administrators stepped in, the professor returned with an apology, but he didn’t stay for long.

“We got this big, long announcement pretty much of him just beating himself up saying ‘I was the worst professor’ and all this stuff,” Fox said. “I mean it kind of seemed like ‘oh, well I got in trouble with the head of my department and so now I have to put this announcement out.’ Nothing about it seemed like anything was really going to fix itself.”

Her hunch was right. Shortly after the announcement, the professor “disappeared again.” The lack of an instructor wasn’t fully resolved until the end of the semester.

“So we had to go back to the head of the history department and he ended up taking over the course at, like, finals week,” Fox said.

There was no explanation provided to the class about the whereabouts of the original instructor, only an additional apology from the new one.

“[It was] just the head of the history department saying, like, ‘I’m really sorry that this happened and I hope that it doesn’t ruin the whole history department for you,’” Fox said. “There was no explanation of where this teacher went.”

Once the head of the history department took over teaching, he immediately began remedying the situation. He canceled the final exam, and relaxed the grading on the final project which “hadn’t even been approved” by the original instructor. Fox felt that her overall grade for the course was a “pretty decent” reflection of what she should have earned in the course. However, the experience made her question other aspects of her college career.

Fox had just declared as a history major, and the course was her “first real experience with a history teacher at the U,” she said. “It kind of made me second guess my major.” She asked herself, “Do I want to keep going if all of the teachers are like this?”

Fox says her history class experience has improved in recent semesters, though.

“I actually am taking another history class this semester and this guy seems really cool,” she said. “So maybe it was just the one experience with the one professor that just wasn’t that great.”

Behind the Scenes

According to Harriet Hopf, interim associate vice president for faculty at the time of The Daily Utah Chronicle’s interview with her, this kind of situation rarely occurs on a campus as large as the U’s.

“We have thousands of classes, so it might happen a couple times in a semester,” she said. “But that would be a really small percentage.”

This small percentage is part of the reason why no official policy or procedure exists at the U to dictate how to proceed when mid-semester replacement of a professor is necessary.

“Because this is so rare, and because each case is so unique, it would be very difficult to write a policy that could be applied appropriately,” said Sarah Projansky, associate vice president for faculty, in an email interview. Projansky wrote, “There are policies regarding faculty leaves for medical reasons (FMLA) and policies regarding faculty rights and responsibilities (Faculty Code). These two policies are generally related to why a faculty member might need to be replaced.”

FMLA, or the Family Medical Leave Act, allows an employee to take up to 12 work weeks of leave for various issues pertaining to the health and well-being of one’s family or self. This is one potential reason an instructor might stop teaching mid-semester.

Part of the U’s Faculty Code outlines faculty members’ responsibilities to students as well as actions that should be taken in the event that they don’t meet these responsibilities. Violations of this code could result in replacement of an instructor.

“I knew [about a case] a couple of years ago where a child was diagnosed with a life-threatening situation,” said Lori McDonald, vice president for student affairs. “So it wasn’t [the instructor’s] health, but it was the health of a child and completely understandable. This person had to go take care of her family.”

The personal nature of FMLA and the rights outlined in the Faculty Code often mean students never learn the reason behind their instructor’s disappearance. It’s also why Hopf calls for students’ empathy and understanding.

“Instructors are people and things happen to people,” she said. “The kinds of things that might make a faculty member disappear tend to be things that are highly confidential and the students in the course would seldom be given details. … Feel some empathy for the person who has disappeared and be kind to the person coming in.”

Even with FMLA and the Faculty Code, each instance of instructor replacement must take many factors into consideration, like department size, course type, instructor seniority and when it occurs.

“Is this a class of 12 people that meets once a week or is it a class of 500 people that meets every day?” Hopf said. She also explained that “it’s a little harder to take over something at the end of the semester because now there’s a whole body of work.”

Amidst all of these factors, one constant is that several people inside and outside the department conduct the transition process.

“When a faculty member needs to be replaced mid-semester, the department chair generally consults with the dean and sometimes with the Office for Faculty,” Projansky said. “[But] each case is unique, so each time the steps may vary.”

For instance, department administration may not be aware that there is a problem.

“Let’s say the faculty member goes out on family medical leave right or sick leave. … That’s a pretty easy one. Like you know when they apply for FMLA, they go out,” Hopf said. However, she explained, “sometimes there may be a problem and nobody knows about it except the students.”

“Students are often the best source of information when there are issues, so when they don’t report, resolution can be delayed,” Hopf said.

Students can report a professor’s “disappearance” to several different administrators, including academic advisors, department chairs and undergraduate studies directors within a respective college. The Office of the Dean of Students is also a resource for students who may not know how to proceed.

“With colleges and departments and all of this stuff it’s kind of hard to figure out how this university is structured,” McDonald said. “So that’s where the Office of the Dean of Students comes in.”

Once an instructor is replaced, the ideals are “to maintain the integrity of the students’ learning environment” and “to ensure the health and safety of everyone involved — the students, the faculty member being replaced, the faculty member(s) who take over teaching the course, and the department and University as a whole,” Projansky wrote in her email. This includes lenient grading and sticking to the original syllabus as much as possible.

“My experience is that, in general, the department always tries to honor the syllabus,” McDonald said. “But again it depends a little bit on the context. … I would say, to the extent possible, they try to honor the syllabus but will make changes as appropriate to finish the course.”

“[With grading] I think there’s a little bit of grace for the students,” Hopf said. “Now, I don’t know if that’s what every student experiences, but that is sort of the intention.”

What resources are available to students?

Although there’s no set policy for how to replace a professor mid-semester at the U, there are clearer processes in place to help students negatively impacted by the replacement. For instance, students who feel their grade was not determined fairly can appeal those grades.

“In policy there’s very clearly a way for a student to request a review,” McDonald said. “If [a student] believed that it was somehow arbitrary or capricious and baseless, there are clear steps how they can have that grade reviewed.”

According to the U’s Code of Student Rights and Responsibilities, students have the right to appeal an “academic action,” which includes the final recorded grade in a course. Students who disagree with their final grade must first reach out to the instructor within 20 business days to “attempt to resolve the disagreement.” If the issue is not resolved within 10 business days after initial contact, then a student may take their case to the academic chair of the department or the dean of the college. After that, a student may appeal to the Academic Appeals Committee.

Students can also drop or withdraw from the course depending on when the instructor is replaced. The drop period for a course is usually the first two weeks of the term, and “it’s never indicated that you were enrolled in that class on your transcript,” according to McDonald.

After the first two weeks, a regular withdrawal period lasts until the midpoint of the semester, during which a student can withdraw from the course without a petition.

“After that deadline, it’s called a late withdrawal,” McDonald said. “So if it’s in the last part of the semester they actually have to go to the college of their major and say ‘I want to withdraw from this course.’ … If it was a situation where it’s a new instructor and it’s not working out, that’s extenuating.”

Retroactive withdrawals are also an option for students, which can be requested after the semester is over. No matter the type of withdrawal, it is notated in the same way on a student’s transcript.

“The ‘W’ on your transcript [gives] an indication that you were enrolled and withdrew,” McDonald said. “But that doesn’t have an impact on your GPA. … And the only difference between a withdrawal and a late [or retroactive] withdrawal is when you do it. It’s not designated any differently on the transcript.”

Another option is a refund for the course, but this is not typically offered by the university for circumstances like these.

“If there was just some really strange situation I could say the university would evaluate whether it made sense to drop students and have it off their record and issue a refund,” McDonald said. “So I wouldn’t say that’s out of the realm of possibility, but I wouldn’t want a student to have that expectation that it would always be [the case].”

Regardless of the ideals, Hopf recognizes that some negative consequences could result from the U’s lack of consistent procedure.

“[The need to replace a professor] doesn’t happen very often, but it does have an impact when it happens,” she said. “And because it doesn’t happen often, it means people aren’t necessarily good at responding.”

Hopf believes an informal document that lists resources for department officials in this situation could help everyone “navigate through it” more easily. “Having a resource that says ‘Hey, this is what you could do’ would be helpful,” she said.