Chavez: Women in Utah Deserve Better

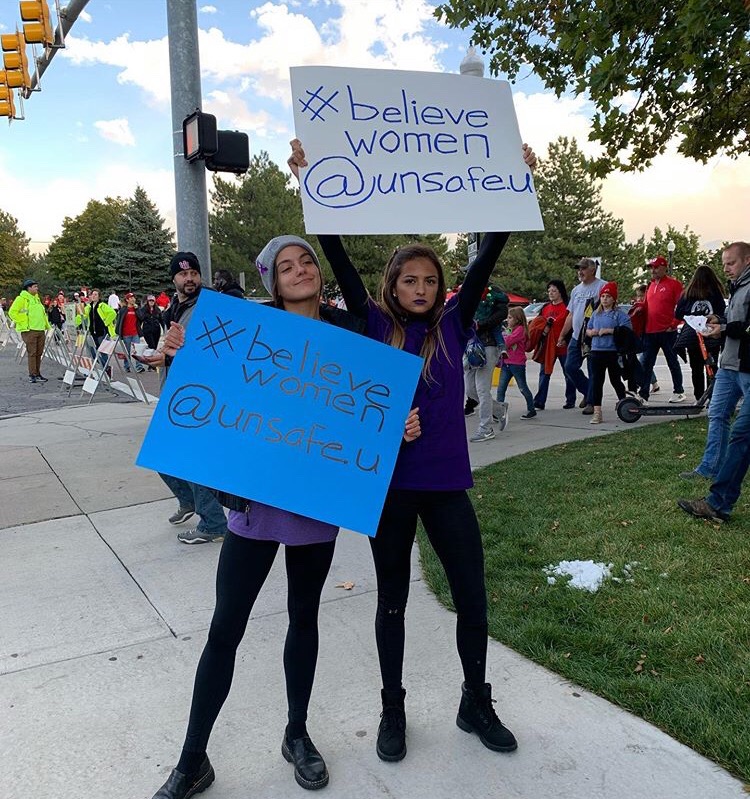

Protestors hold signs with #BelieveWomen. Many students have criticized the U’s motion to dismiss, calling it victim blaming. (Courtesy Unsafe.U)

October 22, 2019

Sometimes it is difficult to believe whether protecting women is really a high priority in Utah.

October has been designated #SafeU Month by University of Utah President Ruth Watkins. The first week began with a “general focus on resources, support, tools, training and other safety information,” including a spotlighted list of 10 things to know about safety. The U launched the #SafeU campaign and website with the intention of creating a “culture of safety” with resources like around-the-clock escorts, consolidated night classes and more lighting and security cameras, but many students, especially those who are female, have expressed that they still do not feel safe. Although the U has implied that they have done all they can to create protections for women on campus, the @unsafe.u Instagram account has collected multiple stories from female students that have not felt protected in their interactions with UUPD, even after the new protocols have been in effect.

SafeU Month is defined by the anger and frustration felt by the many students protesting the university’s approach to campus safety. Organized protests ignited after the State Attorney General’s office filed a motion for dismissal of the $56 million civil lawsuit filed in response to the on-campus murder of Lauren McCluskey and the overall mishandling of her case.

The lawsuit was filed by McCluskey’s parents after months of waiting for an apology for the death of their daughter. The lawsuit names the State of Utah, the University of Utah, the University Department of Housing and Residential Education and the University Department of Public Safety as defendants. While it is common legal practice for a defendant to file a motion for dismissal as the first response to a lawsuit, in the case of Lauren’s tragic death, many see this reaction as victim-blaming and complicit in the silence that surrounds the abuse of women.

The ASUU Assembly passed a resolution that expressed disappointment at the university’s response to the McCluskey lawsuit, and an anonymous Instagram account, @unsafe.u, was “created to highlight the safety concerns at the U.” There is an overwhelming call for accountability and change on the U’s campus. If the administration wants to cultivate and maintain trust with its students and fulfill the promise of a “culture of safety,” the best solution is to actually listen to them.

The specific legal case may come down to whether or not the university violated Title IX and should held be responsible for monetary judgment, but students and advocates of increased safety also see the bigger picture. When a woman asks for help and protection, she should be taken seriously and supported, because abuse can easily become a matter of life and death.

Since Lauren’s murder, the U Police Department and appropriate staff completed Lethality Assessment Program training, which, according to the Utah Domestic Violence Coalition, is “a tool designed to reduce risks and save lives.” LAP trains law enforcement to determine risks and to collaborate with community-based victim service providers to address them. According to the program, “Working together, law enforcement officials and victim service providers are better able to support victims with a variety of processes to include, but not limited to, counseling, housing, medical, financial, legal and other needs.”

Police officers need to be aware of lethality assessment tools. The hours and days immediately after reporting sexual harassment, stalking or domestic violence is an extremely dangerous period for a victim. The risk of retaliation or confrontation is too high to ignore. There needs to be a standard protocol for all police departments to determine and deliver the resources the victim may need.

The Utah Domestic Violence Coalition has worked tirelessly with police departments along the Wasatch Front to implement this protocol, but not all of them have adopted it. Utah state law also has gaps, such as not allowing for a lethality assessment to be applied to those who are in intimate partnerships but do not live together.

Changing this narrow legislation would have prevented the tragic murders of Memorez Rackley and her son Jase in 2017. When she called 911 worried for the safety of her and her family, Rackley reported stalking, threatening and phone harassment from her ex-boyfriend. However, a lethality assessment was not applied because the couple did not ever live together. This assessment could have flagged Rackley as a victim in immediate danger, and she could have been given real resources to find safety. Unfortunately, this did not happen, and her ex-boyfriend shot and killed her and Jase as she was trying to pick up the 6-year-old from school.

Stories like McCluskey’s and Rackley’s are the worst-case scenario for women dealing with an abuser. Horrifically, their stories are fewer examples of exceptions to the rule but far closer to the norm. According to the Center for American Progress, “In 15 states, more than 40 percent of all homicides of women in each state involved intimate partner violence.”

Utah is the worst state for women by many measures, and the police response to intimate partner violence cannot be excluded from that list. Utah needs to do better at protecting women and creating a culture where they are respected and believed. There is no excuse for police departments or universities to deny victims of intimate partner violence protection. Yet, as seen by these alarming statistics and tragic local examples of women losing their lives to abusive men, there is a clear need for systemic and institutional change.

@paijchavez