Chavez: ‘Joker’ Hits a Nerve But Never Goes Deeper

November 1, 2019

Spoiler alert: This article contains spoilers and plot details about “Joker” (2019).

Whether you are a fan of comic books and superhero movies or couldn’t care less, it has been nearly impossible to avoid hearing about the new “Joker” movie. This controversial film has certainly challenged audiences. Maybe you went to the theater expecting an action-packed origin story and left disappointed. Or maybe you were really excited about this new take and left feeling sad but impressed.

Or maybe you fall into the gray, middle ground where I found myself – I didn’t really know what to expect going in, and when I left, I felt uneasy. Despite attempts to dig deeper into why I felt this way, I don’t think I have found a singular conclusion. There is are lots of nuances in the storytelling of “Joker,” some deeply intentional and some unacknowledged. That’s vague, I know, but bear with me. I think to understand the layers of cultural impact, we need to start at the surface, first.

Echoes of Aurora

The first release of “Joker” was met with a mixed reviews and reactions. Media outlets reported about the eight-minute long standing ovation it received at the Venice Film Festival, and there is already Oscar buzz for Joaquin Phoenix’s performance. On the flip side, it was not played at the Aurora, Colorado theater where in 2012 a mass shooter terrorized a screening of The Dark Knight Rises. The theater did not comment on the decision to not show the film, but some family members of the Aurora victims saw traumatic reminders in the promotional imagery of “Joker.” Others worried that it may inspire someone else who feels “socially isolated” to respond with gun violence.

In a letter to Warner Brothers, a group of family members did not ask Warner Brothers to stop the release or change the film, but rather that the studio “end political contributions to candidates who take money from the NRA and vote against gun reform” and “use your political clout and leverage in Congress to actively lobby for gun reform.” They also asked Warner Brothers to donate proceeds of the film to groups supporting victims of gun violence.

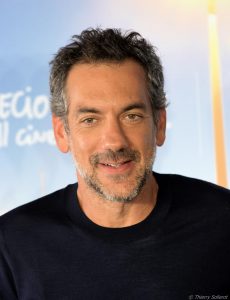

The studio’s response was that they continue to acknowledge that gun violence is an issue and that they have donated money in the past. They reminded viewers that the character in the film is not condoning real-life violence. “Joker” director Todd Phillips argued that art is controversial and should spark difficult conversations. Phillips defended his expression, quipping that “outrage is a commodity,” especially where the “far left” and “far right” are concerned.

A Bleak Commentary On Stigma and Neglect

It seems like we are all tapped into discourse over the “Joker.” My friends on social media had extremely varied reactions — some thought it was too slowly paced and boring, and others thought it was a masterpiece. One common thread was the appreciation of the film’s depiction of mental illness and society’s refusal to truly acknowledge those suffering. Images and quotes from the movie have been widely shared, and the one that was especially poignant to me was, “The worst thing about having a mental illness is that people expect you to behave as if you don’t.”

I think this is true, especially in American society. For me, the slow pacing of the film helped to demonstrate the painful discomfort people with mental illness face when they are mistreated and stigmatized. As an audience, we are forced to feel that along with Arthur Fleck.

“Joker” is set in 1980s Gotham in the midst of intense economic disparity. Fleck loses access to a social worker and medication when the hospital loses funding. Coming to terms with his mother’s own mental illness and the abuse he endured as a child, he feels like he has no identity or social support. The first people he kills are upper-class businessmen that are taunting him on the train, but political protesters support the murders because they misinterpret it as class warfare and not a cry for help. At the emotional climax of the movie, Fleck, now fully embodying the Joker says, “What do you get when you cross a mentally ill loner with a society that abandons him and treats him like trash? You get what you f**king deserve.” He then demonstrates this answer by shooting someone in the head on live television.

XXXXXX

While I agree that the socioeconomic, political and cultural factors that caused Arthur Fleck’s descent into madness and murder have real-life implications, I don’t think that it is necessarily a story that should be told or held up as proof of anything. It is hard to determine whether the filmmakers set out to make a commentary about the social and environmental factors of mental health, or they just liked the idea of attempting a dismal stand-alone story for one of our most popular villains. One New York Times review called it “second rate philosophizing.”

If the creators of “Joker” had grand ideas about flipping the script and making people feel discomfort over how they treat those with mental illness, why is the moral of the story the same tired misconception that disenfranchised will always resort to violence? As written in Insider, “For a movie that does a lot of hand-wringing about our treatment of people with mental illnesses, it sure gives us plenty of reasons to dislike and distrust them.”

This ties into the other problem I have with the confluence of Arthur’s life story and his evolution to Joker. The original and ultimate path of the Joker is to become a criminal mastermind. He runs the underworld of Gotham, he causes chaos for fun and kills people with elaborate weapons. For all his depravity, he is incredibly organized. When we last see Arthur Fleck, he has ended up in the hospital, all of his actions appearing impulsive or as a reaction to being teased or harassed. Do we really believe he is evil now? Realistically, could that character go on to become a super-villain? I don’t think so.

I think that the filmmakers behind “Joker” succeeded in their goals of making a visually-striking and gritty portrayal of how society’s failings can lead a man to murder. They said themselves that their job is not to teach the audience right and wrong, but to make them feel something. And while I agree that they have the right to make the art they want to make, I also firmly believe in my right to speak out against harmful representations of mental health within art. I love art, film and television because I believe in their power for cultural change. Problems arise when those with power and privilege create art that focuses on marginalized groups — in this case, people with mental illness — and unintentionally harm that group in their attempt to deliver commentary.