Cushman: The Revolutionary War Was Not Justified

December 7, 2019

The American Revolution is widely celebrated in the United States during the Fourth of July. The holiday is dedicated to celebrating independence from Great Britain and remains a major symbol of patriotism and pride. The admiration of the Founding Fathers, the Constitution and the Revolutionary War itself was rooted in early American history. However, it may also be possible that the American Revolution was an unjustified revolt against a faraway government that nonetheless fulfilled its end of the social contract and provided protection for its citizens.

Fulfilling Its End of the Social Contract

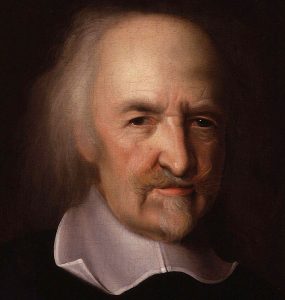

Thomas Hobbes was an early proponent of contractarianism, and believed that people could only overthrow their government when it was not adequately defending them or when their ruler was too weak. Much better known for his contractarian beliefs is John Locke, who believed citizens were obligated to overthrow their government if it was not protecting their rights to life, liberty and property. Social contract theory was the primary justification that revolutionary leaders used to justify their insurgency against the British, but the British crown was not leaving any of its contractual obligations (under Hobbes’s or Locke’s contractarian philosophy) unfulfilled, meaning the rebellion could not be justified.

In 1756, Great Britain went up against France in the Seven Years War, the first war to span the globe. While the fight on the European continent was called the Seven Years War, Americans referred to it as the French and Indian War, as they fought to protect colonial territory from the French and their Native American allies. This war actually lasted seven years, finally ending in 1763 with the Treaty of Paris.

For seven years, Britain fought for colonial territory, accruing debt to defend the interests of their colonies. Part of the post-war peace (and the seeds of tension between the colonies and Great Britain) was the Proclamation of 1763, which forbade all Western expansion into Native American lands past the Appalachian Mountains. What colonists saw as a burden on their freedom was an effort to maintain peace on their continent by a government with an obligation to protect its citizens. With the Seven Years War and the Proclamation of 1763, Great Britain made a clear effort to protect the rights of the colonists and asked for very little in return other than taxes to help pay the cost of that protection.

Colonial Failure to Maintain the Contract

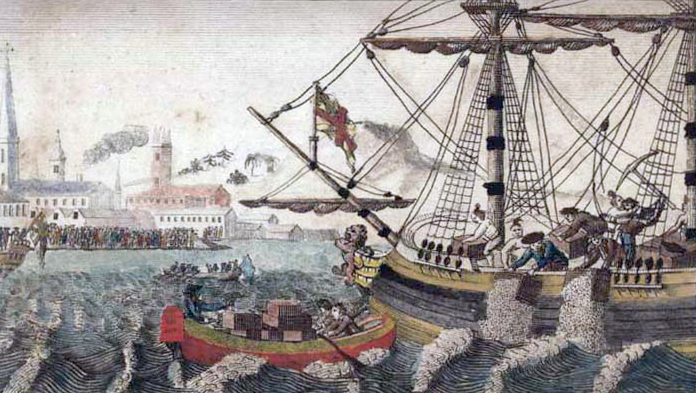

On the other hand, colonists repeatedly broke their end of the contract. Most of the anger toward the British crown resulted from a series of taxes passed after the Seven Years War in part to help pay for the debt Great Britain had earned protecting the colonies and their interests. In 1764, Great Britain passed the Sugar Act, followed by the Stamp Act the next year. In response to colonial “ taxation without representation” outrage and widespread boycotts of taxed products, Great Britain tried to reestablish their dominance over the colonies with the Townshend Acts in 1767. Following this, the colonies engaged in more serious acts of rebellion with the Boston Massacre in 1770 and the Boston Tea Party in 1773.

From March to June of 1774, Great Britain once again tried to assert their dominance over their colonies with what the colonies coined as the “Intolerable Acts,” a series of laws meant to keep citizens who would not peaceably fulfill the responsibilities of citizenship in check. September of that year, the Revolution truly began with the convention of the First Continental Congress, and in 1775, the first shots were fired at Lexington and Concord.

While the British had repeatedly shown its commitment to protecting its citizens, those very same citizens not only refused to help pay for this protection but demanded independence without cause after payment was requested. Their demands for representation, if grounds for revolution, would have meant that the majority of European-British citizens had cause for revolt, as Great Britain at that point in history was a monarchy with a parliamentary system that only granted representation to its lords. The American colonies were even granted some representation through their ambassadors to Great Britain, men like Benjamin Franklin and John Adams.

At nearly every occasion, American colonists tried to neglect their end of the social contract with Great Britain and rationalized their actions and their revolution by accusing their government of doing just that. At every opportunity, Great Britain tried to ensure peace for its colonists, to protect their property and provide representation through entertainment of colonial ambassadors. Americans refused to help pay for a debt they were partly responsible for, undermined their government at every turn and revolted (making an ally out of France, a centuries-old enemy of the British, in the process). Ultimately, the American Revolution is not so clearly justified, as the demands of the colonists were outlandish and the British government treated the colonies with fairness in their governing.

k.cushman@dailyutahchronicle.com

Mike Hawk • Nov 13, 2023 at 3:41 pm

this is pretty silly

Dawn • Jun 12, 2022 at 1:41 pm

I am studying this topic right now in my university class at the University of Phoenix. I am reading primary documents. If one reads the primary documents, one understands that only the American colonies were being required to repay Britain’s war debts. Further, the Seven Year’s War, which began in the colonies but spread worldwide, was fought by the British to take advantage of American resources–colonialism at its finest. The colonists had so many grievances, but here are a couple that stand out to me in Thomas Jefferson’s letter to the King entitled Thomas Jefferson Asserts American Rights, 1774:

“…That these acts prohibit us from carrying in quest of other purchasers the surplus of our tobaccoes…so that we must leave them with the British merchant for whatever he will please to allow us, to be by him reshipped to foreign markets, where he will reap the benefits of making sale of them for full value” (Jefferson, 1774/2014, pp. 123–128). So Britain was restricting free trade and stealing the profits.

“…an American subject is forbidden to make a hat for himself of the fur which he has taken perhaps on his own soil…” (Jefferson, 1774/2014, pp. 123–128). Americans goods and profits were being taken by Britain and they could not even provide for themselves from their own labors. In essence, the colonists were being treated as slaves to pay off Britain’s debt.

Worse, the entire city of Boston was punished for the actions of a few in the Boston Tea Party. All families living in Boston were deprived of their means of making a living. They became destitute.

“On the partial representations of a few worthless ministerial dependents…without asking proof, without attempting a distinction between the guilty and the innocent, who whole of that ancient and wealthy town is in a moment reduced from opulence to beggary” (Jefferson, 1774/2014, p. 126).

Colonists lost many of their inherited rights as British citizens including a trial by their peers. Also, Britain had a standing army in the colonies during peacetime. How would that make you feel today?

Read the primary documents, especially the Declaration of Independence. Actually study the topic and then you will understand…

MaLaBaMi • Oct 5, 2021 at 3:06 pm

For those of you having what kind of looks like a hissy-fit on here debating politics like a couple of 4 year olds fighting over a toy that they both want, (instead of acting mature and just dropping it…) Remember that for someone like me, in middle school, assigned a Civics paper telling us we need to argue for the side of the British, and why the American Colonies were unjustified in leaving Great Britain, this information is quite helpful for us….just you know, keep that in mind

Steve Robert Jackson • Sep 28, 2021 at 11:00 am

i find the whole “Revolution” thing a vast exaggeration by the founding fathers, to cement a degree of patriotic mythology on which to build the Republic. A storyline to which future generations will look back with a great deal of pride and jingoism.

This was astute statecraft with sound foresight, particularly for a federal system which would come to value and rely on a unifying original story.

The reality is that the war was not a revolution, not even close to a revolution. Some historians often like to position it as a parallel revolution to the French Revolution. Some of the same great minds were active in the sphere of both events but the two bear little resemblance to eachother.

The fight for American freedom involved some violent battles but was not the extreme, perverse and often pernicious overthrow of the entire political, cultural & social order that took place in France and for many years after.

In its purest form a revolution as experienced in France, Russia, China etc , results in the complete overthrow of the political institutions and systems from within and the establishment of a completely new order to replace it.

The American war of independence resulted in the creation of a new independent and sovereign nation, with a system that far from overthrowing, borrowed many facets of the British established order, with the exception of the monarchy. Although the early blueprint was simply an alternative form of demagoguery with a lifetime president appointed by the political elite rather than the electorat. Not too far removed from the Aristocratic nature of the British heirarchy. The concept of a freely elected president coming much later.

They also adopted the Westminster bicameral parliamentary system of legislature, and the English common law legal system .

The written constitution was a free think, in order to enshrine the basic rights of the citizen, but this too was put essentially together on the framework of both the medieval English principles of Magna Carta and the 1689 English Bill of Rights.

The most radical and novel things to come out of the independence movement were the separation of powers and the devolution of powers to states within the new federation but neither of these can be described as revolutionary changes.

So the resulting product did not quite reflect the emergence of a radical, revolutionary “phoenix from the fire ” narrative which the founding fathers sought to portray.

As for the British themselves and most Europeans at the time and througout the 19th & 20th century never referred to it as a revolution but simply the “loss of the British colonies in America” later to be defined as the “American War of Independence”.

Josh • Nov 6, 2023 at 9:50 pm

Please never speak again. This assessment is the most embarrassing thing I’ve ever read. I might even show it to an actual historian to get a laugh.

Nobody • Jun 14, 2021 at 12:52 pm

“Democrats re way smarter than you racist, pro-life republican. Learn some respect. Love is love, science is real, black lives matter, Biden 2020.”

The level of projection in this comment is remarkable.

Miles Standish • Apr 16, 2021 at 7:18 am

‘Tyranny’?

I just can’t see it, where on earth was ‘British “tyranny“? The Brits did everything they could to defend our country, they bankrupted their Exchequer and impoverished the people in defence of the US.

Colonial British Americans or English Americans had the highest standard of living in the world more even than the British in the UK! Yet, the moment they asked us to pay a small tax to help re-supply and pay the wages of the troops defending the US it was called “tyranny“ and a cause for rebellion. In closing , when you look at all the other British colonies, particularly the English-speaking colonies, they all gained their independence once they were economically and militarily independent with a functional democratic government. Therefore, there can be no doubt, America would’ve also gained its independence if it had waited like Canada, Australia and New Zealand for a few more years. When I look around at what is going on in America I sometimes wonder if we shouldn’t have just waited, why? Isn’t it obvious? Canada, Australia and New Zealand are all stable, healthy democracies with none of the problems that we seem to have……

Michael Ben David • Feb 19, 2021 at 12:02 pm

Cmon with the rudeness. You can have an opinion that is different than someones and not be mean or rude about it. I’m looking at you DT.

The most important fact to counter this article though is the Proclamation of 1763. The British only protected the interest of the motherland in removing the French from the Ohio River Valley. The colonists who fought the war were banned from settling there in order to form an Indian State. Obviously the colonists did not take kindly to that and proceeded to settle there anyway, which created lots of issues for many parties.

For the record, I don’t subscribe to the fact that England’s tyrannical rule was the sole reason for declaring independence. There were several factors, some just some not. Whether or not England was genuinely tyrannical is up for debate. What is true is that many colonists had legitimate reason to dislike the policies imposed on them from across the ocean.

Historical empathy does not equate political sympathy.

Joey Smith • Feb 12, 2021 at 12:48 pm

Stop turning this into a political battleground y’all. Both sides could easily be argued. Apple Pie

BIG BRAIN • Dec 1, 2020 at 11:55 am

y

Professional baller • Oct 4, 2023 at 9:07 am

pp poo poo haha

Wesly Alfred • Oct 9, 2020 at 10:01 am

DT on December 8th, 2019 12:37 am, what do you mean “I guarantee she is a Democrat”? Democrats re way smarter than you racist, pro-life republican. Learn some respect. Love is love, science is real, black lives matter, Biden 2020.

Cap Caputo • Dec 24, 2019 at 1:49 pm

I can see her points. After all, the colonists had Samuel Adams and James Otis, two hot heads who only wanted a revolution, instigating and agitating things in New England. However, her arguments make me believe she is a Tory. Enjoyable reading but I disagree with her; the colonists had justifiable causes. Could have independence been granted by England peacefully? I doubt it. Once the King and Lord North dug in their heels and refused to loosen the acts, it didn’t take much for Adams and Otis to flame the fires of revolution a little more. When the march towards Lexington and Concord commenced, there was no avoiding the inevitable result.

DT • Dec 8, 2019 at 12:37 am

This chick’s marxist professors have done an admirable job at removing her brain. This is another veiled attempt at historical revisionism. I guarantee she’s a democrat.

Mike Hawk • Nov 13, 2023 at 3:43 pm

Someone woke up on the wrong side of the bed.

GE Seneff • Dec 8, 2019 at 12:36 am

Nice attempt at rationalizing tyranny. Anyone who truly studies the era will recognize the numerous violations of Britain’s own constitution. “Taxation without representation,” was only one of 21 causes of the revolt as listed in the Declaration of Independence. If you don’t mind the forced housing of government troops in your house and confiscation of personal property, for example, then I can see why you think the colonists had no basis for their grievances.