Scott: The U Is Losing Its Opportunity to Repair Its Relationship With Students

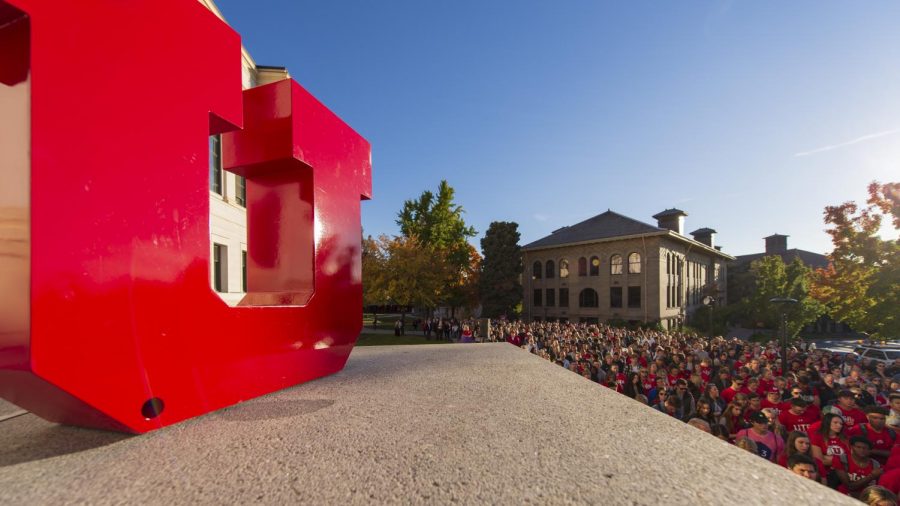

Students, staff, family and friends attend a vigil on the steps of the Park Building for Lauren McCluskey who was tragically killed on campus at The University of Utah in Salt Lake City, Utah on Wednesday, Oct. 24, 2018. (Photo by Kiffer Creveling | The Daily Utah Chronicle)

February 6, 2020

Like many senior students within sprinting distance of graduation, my final semesters have been cobbled together with whatever classes remain between me and my degree. It can be challenging to create a realistic schedule of stragglers, but I am lucky my schedule is only inconvenient in that it often keeps me on campus well past nightfall. Still, while I do not mind long hours in class or working late in the library, I cannot help but feel apprehensive each time I leave for the night, stepping out through the doors and into the black.

I am well-acquainted with the mental checklist employed by all women during their solitary walks in the dark. From childhood, we learn to give suspicious silhouettes (of people and anything big enough for a person to hide behind) a wide berth, to be aware of others while being inconspicuous ourselves, and to walk fast, look over our shoulders and be prepared to run. And while I am aware that, statistically, I am more likely to be assaulted by an acquaintance than a stranger who pounces from behind a corner, it is difficult to shake that fear. Still, as necessary as this ritual of self-preservation feels, it provides no illusion of safety.

The fact that I take these precautions whenever I am alone outside at night feels demeaning and unfair. Violence and sexual assault shouldn’t take up this much of my mental real estate, but they do. Getting from point A to point B feels like a hazard, and for all the nervousness I feel in the moment, I often tell myself I have overreacted later. I have seen enough women talk about similar fears only to be called weak and obnoxious by people who don’t understand, and there appear to be many of those people at the University of Utah.

From the beginning, my time at the U has coincided with campus-wide fear, trauma and loss. On Halloween 2016, a woman reported that she was raped at gunpoint by a masked man in her vehicle, which was parked in a campus lot. I was preparing to attend the U at that time, and shuddered as I read the news alert — I felt sickened for her and was concerned when I read about the dismissive email from then University Police Chief Dale Brophy. (A few months later, federal officials found “potentially serious shortcomings” in the university’s crime reporting process after investigating this incident.)

Two months later, Katherine Peralta was killed by her husband in a U research parking lot. She worked and died in the same University Research Park where my boyfriend and I took regular evening walks. My boyfriend lived in university dormitories, where we would cower in a closet during a lockdown the following October after Chenwei Guo was gunned down in the parking lot outside.

The October after that, Lauren died. Every time I sit down in an attempt to write about Lauren McCluskey, I end with my face in my hands. There is little to say that hasn’t already been said — she did everything right, she wasn’t believed and the U still does not seem to be listening. Thinking about Lauren feels like an endless horror movie — I can visualize her struggling to escape, to get help, as we the bystanders blankly turned away. The danger was not her killer alone — it lives within every university officer who ultimately denied her.

The tragedy does not even end there. In January 2019, U of U doctor Sarah Hawley was murdered by her boyfriend. In February, an officer who mishandled McCluskey’s case mishandled a second domestic violence incident. Less than six months later, McKenzie Lueck, another U student, was found dead. A few months after that, reports surfaced that a U student had trapped a teenage girl in his dorm room and left a voicemail threatening to kill her — and that university police had again mishandled the case.

This is a truly frightening amount of police incompetence, violence and death to occur within the span of a few short years. No wonder students and their families feel angry and afraid. I recently saw this with my own 12-year-old brother when I took him to a store filled with U merchandise. As we walked inside, I put on my best supportive older sister voice and asked him if he is still planning to go to college and if he would ever like to go to the U. He looked around at the U logos plastered on the walls, paused, and asked, “But don’t people die there?” This kid doesn’t need to read the newspapers to see the U’s growing reputation.

I understand that the U could not have prevented or even acted in every case. Several of these incidents were unpredictable, happened off campus or occurred without the campus police being aware of the risk. But others were not, and the university police have clearly demonstrated their ineptitude in addressing domestic violence. The resulting distrust has caused many students to feel like they are on their own if something terrible happens. A male freshman student recently asked me if I, as a woman, would go to university police if something happened to me on campus. Surprising even myself, my answer was a simple, unemotional “no.”

Trust is complicated, especially as it pertains to creating a safer campus community in the future. There are many individuals, organizations and societal factors at play (with plenty of blame to go around) but I fear that the unwillingness of the university to accept accountability where it is due has set this conversation upon a path without a resolution. The healing of a community and the restoration of trust do not come free. They do not even come through hard work if the work looks and feels like PR. Responsibility is the core of leadership, and good leadership serves to unite. It hurts to see that the university continues to struggle to understand this.

I understand where the U is coming from when it says that its proposed changes will make the campus safer than ever, but this is about the university-student relationship just as much as it is about installing alarms and increasing patrols. Statistical knowledge about my safety brings me cold comfort as I scuttle through campus, fearing the terrible things that have happened here to students like me and knowing that university police mishandled them. There will be a steep price for allowing the bonds of student — and public — trust in the university to atrophy. It runs deeper than the disappointing headlines and the fraught interactions between students and university leadership. Losing trust in my university, where I have enjoyed priceless learning and growth, is not a place I want to go, but it feels increasingly difficult to rebuild as things currently stand.

This article was originally published in print on Oct. 28, 2019.

Mark • Feb 9, 2020 at 12:12 am

“My boyfriend lived in university dormitories, where we would cower in a closet during a lockdown…”

A generation ago, when men were not ashamed of displaying certain masculinity traits and in fact were expected to show some, it would be unfathomable for a man to be hiding in a closet in a situation like that. Times have surely changed…