Emery: Time to Move Past the Whitewashed Wild West

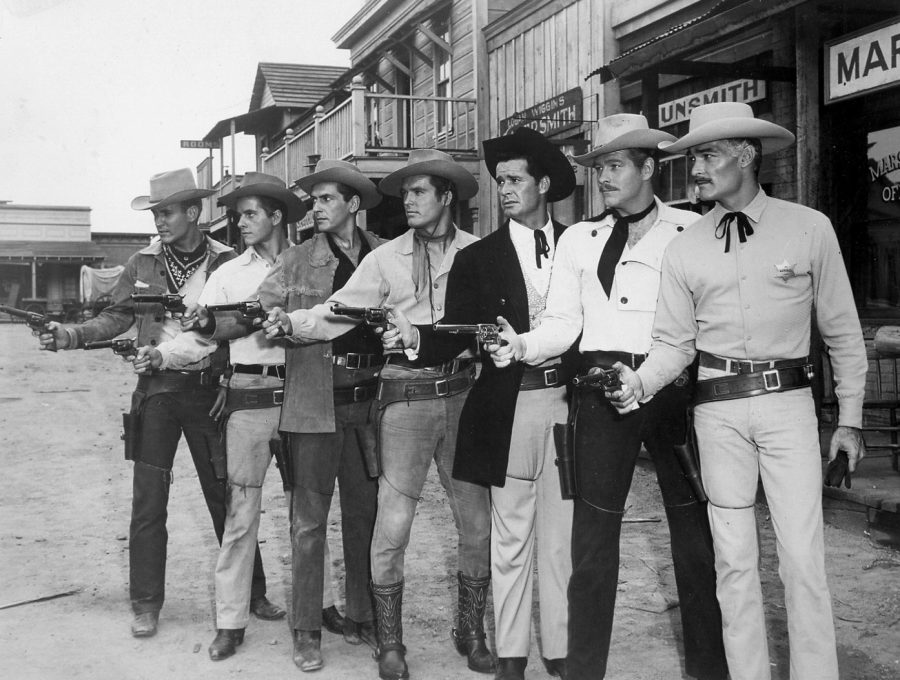

“Classic Westerns from the mid-20th century are critical to our understanding of race in contemporary America.”(Courtesy Wikimedia Commons)

March 28, 2020

The scene opens with a wide-angle view of the Great Plains. Mighty winds blow clear across the grass as smoke billows from the stack of a train far in the distance. Two men on horseback enter the frame. One is white, wears a white hat and sits astride a white horse. The other is his Native American sidekick — a racist caricature carefully crafted to be consumed by all-white audiences in early 20th century America. As they ride, the white cowboy, ironically, tells his companion about a bygone era when cowboys ruled the plains, sighing before saying that his way of life is under threat. He does not understand this new world where railroads and telegraphs have replaced wagon trains and the pony express.

The fundamental myth of the west is white, rugged, masculine individualism that claimed that “anyone” willing to brave the frontier could find a new life for themselves. By depicting a tough, brave white man as the embodiment of justice in a savage and lawless land, classic Western films demonstrate how exclusive that new life truly was. Classic Westerns from the mid-20th century are critical to our understanding of race in contemporary America.

Sidelining the Sidekicks

Sidekicks are a common staple in Westerns. The sidekick’s role was to do the dangerous work and allow the white cowboy to take all the credit. Perhaps the most famous sidekick is Tonto, the Native American companion of the Lone Ranger —whose white character was likely inspired by a black deputy marshal named Bass Reeves. Tonto was depicted as an intelligent master hunter and tracker who was incredibly loyal to the Lone Ranger.

Despite these seemingly positive character traits, Tonto — most famously played by Native American actor Jay Silverheels — was reduced to the “Noble Savage” trope that was common in this genre. The director depicted his intelligence and loyalty as the exception among Native Americans, not the rule. The trope taught white audience members that there were “good minorities” and “bad minorities,” with the distinction between them being their subservience to whites. No matter how talented, moral or loyal the minority was, they were still a minority destined to be forever relegated to the background.

Westerns were one of the most popular genres in the early film industry. They were massively popular both in theaters and as television shows from the ’30s through the ’60s. Roughly during the same time period, several Confederate monuments were constructed and the Jim Crow laws in the South were further entrenched. While the Jim Crow laws were de jure segregation measures implemented by states, western films (similar to Confederate monuments) were examples of de facto discrimination. Their intent was to intimidate minorities and reinforce the belief of white audience members that white men, the symbol of justice and good, are on a moral crusade. Anyone in opposition to the white man in any way was, by definition, evil and threatening to an entire way of life — or, more accurately, a system built on systemic oppression and dehumanization.

Westerns Sell Only One Kind of Hero

Many people alive at the time would have remembered when the Western frontier had closed, the principles of American exceptionalism and Manifest Destiny were supposedly proven right. Yet the same rugged, masculine individualism that defined the west would eventually become obsolete, and westerns were an attempt to hold on to that fleeting memory in film. Even though one in four real-life cowboys were black, cowboys in westerns are uniformly depicted as white. In addition to erasing black heroes, the portrayal of white men was an early form of propaganda. They were the symbol of justice in the Wild West, protecting the frontier, their towns and their women from bandits and invading bands of Native Americans.

Western films offered an increasingly urban and professional white man the opportunity to escape back into the mythical frontier and imagine himself as the hero of the Great Plains. Westerns reminded the white man of what he already believed — that the United States was his country. Minorities may live in America, but the white man’s ancestors were the ones who were chosen by God to tame the west. This parasitic thought burrowed deep into his psyche and has infected generations of white men to this day and has helped to reinforce a social power structure centered around white superiority.

The Future of Westerns

The 2019 film “Queen & Slim,” with its many similarities to “Bonnie and Clyde,” is a take on the neo-western genre. In the film, a black man and woman are on the run from Cleveland through the Deep South — fleeing law enforcement after the accidental death of an officer during a traffic stop. At one point, while Slim is on a horse, Queen tells him that nothing scares a white man more than a black man on a horse. When he asks why, she replies, “because they have to look up at them.” The best answer to the white male domination of Westerns is not to throw away the entire genre, but to make new films starring the long-under-represented black cowboys.

Quentin Tarantino’s box office hit “Django Unchained” is a perfect encapsulation of a black cowboy challenging the myth of the Western. Jamie Foxx stars as a fictional slave who gains his freedom and allies with a bounty hunter to free his wife, but new, fictional characters do not have to be created to tell these stories. The life of Bass Reeves should be reclaimed from the Lone Ranger and retold. The stories of the black men on the frontier who really existed can be pulled from the historical record and would make for incredible films. The western is not a dead genre — in fact, many of its ideals are still relevant. It’s about time the protagonists are representative of the reality of life in the Wild West.

John Galloway • Apr 10, 2022 at 2:38 pm

Yes, the Frontier was settled by and large by men of white European stock. Why is this an issue over a century after the fact ?

George Bruant • Jan 10, 2021 at 10:05 am

The Reeves/ Ranger Myth was invented out of whole cloth, has no basis in fact and blatantly whitewashes the Black lawman’s legend, so that now Bass Reeves’ “real” story is becoming unrecognizable from the PC fluff.

Art T. Burton • Mar 29, 2020 at 3:27 pm

Very good article! I wrote the books: Black Gun, Silver Star: The Life and Legend of Frontier Marshal Bass Reeves and Black, Red and Deadly: Black and Indian Gunfighters of the Indian Territory, 1870 – 1907. My website is: art burton.com