Scott: Racism in Utah Schools Leaves Long-term Wounds

June 5, 2020

The youth are our future, which is why it is concerning that so many recent high profile acts of racism in Utah have come at the hands of high school students. Whether it be slurs at basketball games or ignorant scribbles in yearbooks, white Utahns have a long way to go in building a community that is safe and accepting toward everybody.

In 2013, the Canyons School District settled a lawsuit after an Alta High football player threatened to lynch a student, saying “Isn’t it funny that thirty years ago you would be hanging from one of these trees?” In 2016, a crowd at Emery High yelled racial slurs at Summit Academy students during a basketball game. In 2017, five Weber High cheerleaders filmed themselves saying “F— n——” amid shrieks of laughter. At a 2018 school dance, a white Layton High student shoved a black student, spitting on his face and calling him a “n—–.” The same year, two Sky View High students were harassed during a soccer game by people yelling “Black lives don’t matter” and “nice shot, n—–!” In 2019, vandals drew racial slurs and a swastika at Herriman High and Copper Canyon Elementary Schools. This was the same year two Hurricane High students posed with a Confederate flag, a white hood and blackface in a photo captioned “N—– hunting 2019: I’m glad I could fill my tags this year.” And just last week, Orem High’s softball field was vandalized with racist and homophobic slurs.

It’s tempting to say that “this isn’t the Utah I know.” Utah enjoys being known for fry sauce and superior snow, the 2002 Olympics and the Mighty Five. It is a beautiful place — but we cannot tout an idealized version of our home while ignoring the trouble brewing within it. This is the Utah we know. We have a problem with racism in our schools, and we regularly fail to defend those targeted.

While most students do not participate in violent acts of racism, we discount how much harm is dealt by kids we consider to be “regular” and “good.” I remember well-respected kids at my high school who called a black classmate “Blackie” and regularly laughed at Holocaust jokes. And I remember regular kids like me, who, despite our disgust with the racism, never came to the aid of our classmates. Whether we dole it out ourselves or idly stand by, we are all implicated.

Flipping Through the Yearbook

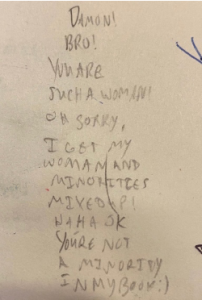

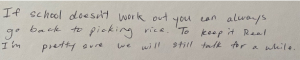

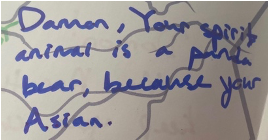

This takes a toll on students of color, no matter how playful, ignorant or ironic the perpetrators claim to be. A recent Twitter thread by University of Utah student Damon Ngô perfectly encapsulates the weight that many students of color carry beyond the high school doors. Ngô shared several photos of his old high school yearbooks, their pages filled with notes from his classmates. Some were bewildering, others were downright derogatory. I reached out to Ngô to ask him about his experience. While he remembered there being some odd comments about his Vietnamese heritage, it wasn’t until recently that he realized how far they’d crossed over the line.

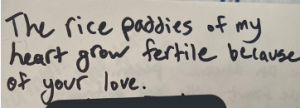

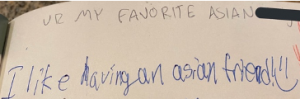

Comments like “You’re the best Asian!” appeared over and over again. One classmate called Ngô “My favorite foreign homie.” Other comments got uglier. “The rice paddies of my heart grow fertile because of your love,” wrote one classmate. “Damon! Bro! You are such a woman! Oh sorry, I got my woman and minorities mixed up! Haha jk you’re not a minority in my book,” said another. One classmate went so far as to write “If school doesn’t work out you can always go back to picking rice.”

“It was normalized for me,” said Ngô. “I had always tried to fit and mold myself into what other people expected me to be, into almost a caricature of my culture, the model minority, and the stereotypes that people projected onto me. It was tough to understand who I really was outside of those things.” This realization motivated Ngô to tweet the photos to see if any of his followers shared his experience. A few big accounts picked it up, causing the thread to go viral.

Some argued that anyone who tolerates such behavior is weak — “implying that I was responsible for the racism against me,” said Ngô. But others strongly identified with his experience. “LGBTQ people who were outed or came out in high school had similar experiences. People in the Asian American community, the African American community, almost any community you can think of, felt like they were placed in a similar box and tokenized in these ways. That moved me the most,” said Ngô, citing the responses to his thread.

Death by a Thousand Cuts

High school isn’t an easy time for anyone. The transition into adulthood is tumultuous, and young people constantly grapple with the question of who they are. The burden is heavier for students who weather constant barbs about their identity. Ngô remembers how classmates conflating his Vietnamese heritage with other countries or simply dubbing him their “Asian friend” fractured his self-image.

“They really saw Asian culture as very monolithic,” said Ngô. “A lot of people don’t even understand regional and geographic differences in Asia. Growing up, a lot of people have asked me ‘so, just to be clear, are you Chinese or are you Asian?’ I think that’s probably the case for people of color from other regions, such as African countries or the Middle East, there is that same deconstruction of identity.”

Ngô also experienced confusing “positive racism.” He was expected to be good at math and destined for success — assumptions that are still racist, but rarely interrogated. “It’s a constant battle of what do I make a big deal about and what do I not,” said Ngô. “Survival is the key in high school and growing up, especially if you are in a community that is not like your own. They don’t realize that you’re in a box. You see a lot of these people every day, and most people are just trying to get by.”

“You Are My Favorite Asian Friend”

Perhaps the most disgusting aspect of racist bullying in high school is that it often comes from friends. The familiarity of friendship may lead to a sense that any joke is fair game — and when someone is inevitably hurt, it will all be written off as humor. That was certainly what I saw during my high school years, and Ngô’s experience demonstrates the same.

“I think there was a correlation in their minds, that my ability to allow that language to be used against me somehow meant that I was closer friends with them,” said Ngô. “I don’t think I acknowledged that at the time, that there was a sort of ‘how can I push this and how far will he let me push this.’ I think there was an assumption that the further I allowed it, the more they felt I was their friend and comfortable with it, that he must be a really close friend if he is allowing me to be racist to him.”

Many people think of racism as a simple binary: either you are a racist, or you are not. For those with this view, friendship with a person of color is the ultimate arbiter of their lack of racism. According to Ngô, “It did something to quell [his classmates’] guilt, to have someone in their circle who was a person of color who allowed them to be more ‘culturally adept.’”

But racism doesn’t work that way. It doesn’t matter how many people you’re friends with, how many books you’ve read or which party you vote for. Racism is a powerful construct that is taught and reinforced, rinse and repeat, in our country. Even the most well-meaning, self-aware person will commit racist thoughts or acts — what matters is their willingness to recognize this, offer restitution and improve themselves going forward.

Taking Steps Forward

Most people outgrow their high school selves and prefer not to be defined by their awkward teenaged years. But personal growth does not heal the wounds of others, and as Ngô pointed out, “this behavior isn’t confined to a certain time frame or a certain period of our lives.” For those who have perpetuated or enabled racist bullying in the past, there are opportunities to make amends. They do not involve teary apologies or self-flagellation. Standing up against future racism is the best way to show a change of heart. “When they come across behavior like that, I would urge them to call it out and be an ally,” said Ngô. “Not so they can look good and tweet about it later so that you can look like an ally, but because we are all responsible, to an extent.”

Do not give into the expectation that those victimized by racist rhetoric are ought to stand up for themselves. Too often does the burden of starting conversations rest upon the marginalized — especially now, as anti-Asian and anti-Semitic sentiment rises in the wake of COVID-19 and America is rocked by anti-black police brutality. It is necessary that people acknowledge the power of their own voice and use their privilege to fight the racism they will never experience themselves.