Social Media is Integral to the Black Lives Matter Movement

Protesters raise their signs in Salt Lake City, Utah on June 4, 2020. (Photo by Manasij Mukherjee | The Daily Utah Chronicle)

July 6, 2020

From both the studies of Black historians and the anecdotes of older folks in my life, I’m hearing a common message: 2020 feels like the late 1960s. Although Black activists never stopped calling for change over the past five decades, the United States hasn’t experienced a nationwide protest since 1968, in the weeks following the assassination of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

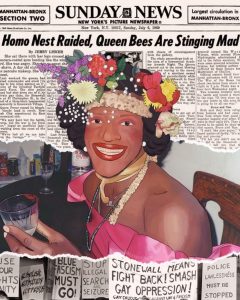

In many ways, the modern Black Lives Matter movement parallels the Civil Rights movement. Public conversation regarding centuries of systemic racism has been on the rise and the murder of one Black man has catalyzed massive multiracial engagement with pre-existing causes. And just as relevant as in the counterculture era of the 1960s to ‘70s, today there is a young, angry generation paired against a dogmatic, out-of-touch federal administration. But there’s one element that clearly distinguishes these protests from any other in U.S. history: the accessibility of photography and videography. These art forms haven’t been in the hands of everyday people for very long, and have never been exchanged more easily than they are now — thanks to social media.

Although it was the murder of George Floyd that ultimately triggered the latest protests, it was the bystander footage of that murder that shocked previously uninterested individuals into paying attention. Graphic videos of Black deaths are unnecessary and traumatic for those who are keenly aware of the violence against Black Americans — and when these videos go viral, they can even serve to normalize it — yet this latest piece of irrefutable evidence was enough to force many Americans into acknowledging the problem.

But powerful visual media didn’t just incite the current uprising — it continues to propel it. Photos of protest signs, digitally designed quotes, murals and posters honoring those killed by police, infographics on how to be anti-racists and videos of police brutality have dominated social media for weeks. Individuals are directly exchanging information and creative expression with one another en masse, outside of the traditional top-down channel of information flow. In this way, the Black Lives Matter movement is effectively an art movement.

Guerrilla Journalism Empowers Protestors

For decades, narratives on pressing national issues — from the war in Vietnam, to the war on drugs, to the war in Iraq — were largely written by the White House and a handful of mainstream media conglomerates. Until recently, no streamlined citizen-run communication existed. Now we have social media, in all its messy, empowering and dangerous novelty.

To those who are observing the current protests from a distance — a distance that’s often bridged by corporate newspapers or cable news media — the protestors might seem aggressive, while police civilly maintain law and order. But to those who are a little closer to the protests — whether through direct involvement or through eyewitness accounts on social media — a different picture emerges. Salt Lake City resident and protestor Sergio Gomes noted a disconnect between the events at these protests and their coverage in local cable news. Of the first protest that occurred here in Salt Lake City, Gomes said, “Different news outlets were framing the protestors as all rioters and looters, but when you’re on the ground, it’s 99% peaceful. They’re using their rights to free speech. I think the people on the ground reporting are doing a better job of presenting the protests than corporate media.”

The rise of social media has ushered in an age of guerrilla journalism, giving the American public access to information we wouldn’t otherwise have during these tense citizen-state relations. For example, when the Trump administration recently used federal police to violently clear out peaceful protestors for a photo-op at a church, the Washington Post’s coverage relied entirely on protestors’ cell phone footage.

Meanwhile, here in Salt Lake City, KSL and Fox13 gave considerable attention to the story of police kneeling in solidarity with protestors but completely ignored the story of police cornering and repeatedly shooting a peaceful protestor just a few blocks away, even as footage of the incident circulated Reddit and Twitter (in response to the viral video, The Salt Lake Tribune covered the story a few days afterwards). In another striking example, Police Chief Mike Brown claimed that an officer was present in a police vehicle at the time it was burnt by protestors. But after multiple cell phone videos proved him wrong, Fox13 updated their article to include a notice of the erroneous reporting.

Similar is the case of Taylorsville resident Brandon E. McCormick, who was recorded parking in a crowd of protestors and firing a bow and arrow on them before being assaulted by the group in self-defense. Chief Brown explained that after officers rescued McCormick from the crowd, “It was only later through the media inquiries and shared footage that we were able to identify him and a series of events that preceded.” Charges were filed against McCormick three days later due solely to the citizen footage of the event, which has been viewed nearly 16 million times on Twitter.

A Salt Lake City resident and woman of color who chose to remain anonymous commented,“Verbally, people can say whatever they want, but when you have visuals, you can’t argue with facts.” She continued, “We are dealing with people’s lives — seeing what’s going on will help spark the conversation to help change things.”

Social Media Can Be a Double-Edged Sword

Despite its unique ability to ignite conversation and document eyewitness evidence, social media is also working against the Black Lives Matter movement. Most social media is designed for users to selectively show off fragments of our personalities and our lives, which can create insidious gaps between what we post and how we behave. In one personal example, sharing an informative podcast episode on prison abolition was far easier and far more visible than actually integrating, into my daily life, what the podcast taught me. I’m still working on that last part.

In a broader example, although it was originally intended to display support for the movement, a day full of black squares on Instagram actually stifled valuable protest information as well as all

owed otherwise uninvolved social media users to take part in a short-lived trend, without substantiating the hashtag #BlackLivesMatter with real action. Twitter user @slashatrashton asks non-Black folk, “what have you done for BLM? Does it go beyond social media? Did you just post the black square and go? Did you donate anything? Sign any petitions? Are you actively engaged in conversations about antiracism and what is going on with your community?”

As the aforementioned anonymous woman of color and Salt Lake City protestor noted, “Way too many non-Black people are sharing their visuals [while at protests] like it’s a photo op… like they have to share that they are a part of the newest trend, not sparking any change in their lives or conversations.” She went on to explain that snapping photos of Black and brown protestors puts their safety at risk, but “recording police and sharing people’s signs without including faces helps the movement.”

Kevin Gaines, a professor of Civil Rights and Social Justice, notes in an interview at the University of Virginia that we can’t quite be sure yet whether social media will ultimately be constructive for the movement or not. Gaines does, however, note that “The rise of social media, and the Black Lives Matter movement, raised the consciousness of a substantial segment of the public about systemic abuses of power by law enforcement, white privilege and the racist scripts broadcast in the media that seek to legitimize police and vigilante violence by criminalizing black victims.”

In this collective cultural conversation, what we choose to share and pay attention to online is particularly salient. Just as our choices online can be hollow — signaling nothing but our desire to not be seen as racists or to ignore oppression — so can our choices online be authentic and tethered to actual changes in ideology and behavior. Sparked by conversations regarding the protests on social media, books on anti-racism have skyrocketed in popularity, cities have seen surges in voter registrations and bail funds have received tens of millions of dollars in donations.

Black Lives Matter is the resistance art movement that is defining 2020. As a white person who is continuously learning how to dismantle my complacency with white supremacist systems and ways of thinking, I am grateful for the following activists and artists who educate and inspire me on social media: Future Earth, India Renee, Brandon Kyle Goodman, Josie Duffy Rice, Dr. Ayana Elizabeth Johnson, We The Urban and Mikaela Loach