‘I Was a Simple Man’ is a Hypnotic Meditation on Colonization, Mortality, and Nature

January 30, 2021

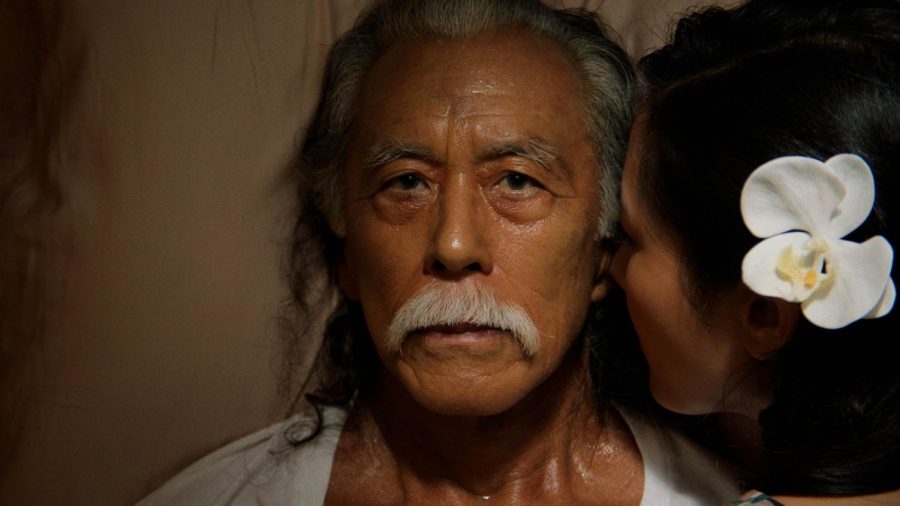

“Dying isn’t simple, is it?” asks Grace (Constance Wu) constantly throughout this story. The question sticks to Masao (Steve Iwamoto) as his impending death forces him to confront complicated and haunting scenes of his past, present and future in rural Hawaii. Directed by Hawaiian filmmaker Christopher Makoto Yogi, “I Was a Simple Man” premiered on Jan. 29, 2021, at the Sundance Film Festival.

A Trance-Inducing Experience

Provocative landscape shots of Oahu collaborate with close-up shots of Masao’s daily life to induce viewers into a trance. There is little dialogue and even less of a score. Yogi uses both as very intentional tools to guide our near-hallucinogenic experience only as necessary. Instead, what we hear is what Masao hears: wise trees, excited birds, unforgiving rain, angry construction, whispers from the people he disappointed decades ago. What we see is what Masao sees: plants that need watering, pill bottles, plates and beer cans from family picnics, glimpses of a future beyond the United States’ dominance over the land. This unique sound mixing and cinematography make for a magical meditation.

The plot of “I Was a Simple Man” flows more like a stream of memories and dreams than a structured narrative — in the same way that the rain trickles effortlessly through the leaves and into Masao’s home. The film is also very slow, as the entire second act transpires without any single event that can be easily described. This pacing paired with a surrealist feeling can be disorienting at times, but the more I paid attention while watching, the more I saw that this film knows intimately where it is going and what it wants to offer to viewers. The story is as rooted and alive as the sacred Hawaiian trees that Masao and Grace promise to never leave.

An Exploration of Colonization

“I Was a Simple Man” manages to communicate a volatile history of colonization with mindfulness and gentleness. We are not given a history lesson nor told to be angry or sad; instead, Yogi asks us to pay attention to how these scenes feel — how these questions of human suffering and resilience feel. What is it like to be torn between loyalty to one’s homeland and loyalty to one’s family, who have been uprooted from the land by violent external influences? What is it like to struggle to forgive, while begging for forgiveness? What is it like to die?

As viewers, we are not allowed to ignore these questions just because they might be uncomfortable. Painfully long shots force us to join Masao in the depths of his isolation — even after the scenes seem like they should have ended. Intense and overwhelming sounds of urban development beg us to understand that the land is being carved out by hands who do not love it — as we listen, we are aware of this in our own bodies. We feel it the way Masao and generations of real-life Indigenous people feel it. But we also feel Masao’s and Grace’s timeless spiritual tie to the environment; we see that our symbiosis with nature outlasts everything else. I have never been to Hawaii, nor is the disruption of one’s native culture something I have personally experienced, yet Constance Wu’s magnetic depiction of a messenger frozen in time and space still felt like it was meant for me specifically.

What makes “I Was a Simple Man” remarkable is that it is not just a ghost story or a social commentary or a practice in mindfulness. It’s all of these, and simultaneously something more that I have yet to accurately put words to.