Saifee: The Stage is Set for Gentrification in Salt Lake City

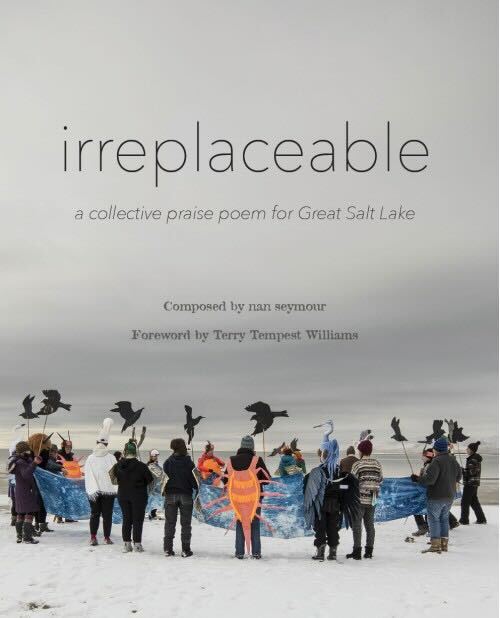

A development project underway off of 500 S and 1300 E in Salt Lake City on October 15th 2020. (Photo by Gwen Christopherson | The Daily Utah Chronicle)

April 12, 2021

Utah’s population is booming — thanks to economic growth in Salt Lake and Utah counties, and a relatively low unemployment rate despite the pandemic. People from California and other western states are flocking to Utah in pursuit of economic stability. However, Utah’s housing infrastructure is ill-equipped to handle our growing population — even before the pandemic, we faced a housing deficit. But more pointedly, the real issue is that Utah prioritizes housing development for middle-class families and young entrepreneurs over affordable housing for lower socioeconomic status and often Black, Indigenous or people of color. Utah is experiencing “growing pains” — inadequate housing for the most vulnerable and the gentrification of our most diverse neighborhoods.

At first glance, gentrification doesn’t seem harmful, as it is the process of revitalizing neighborhoods to boost market value. New apartments and businesses are built, attracting wealthier residents and subsequently increasing the property values and prices in that area. While the rebuilding of infrastructure isn’t inherently bad, the increasing prices displace many of the original residents as they cannot afford the new prices. This displacement disproportionately impacts lower socioeconomic status and marginalized communities. The “urban renewal” coincides with “minority removal,” leaving many people in vulnerable housing situations.

Gentrification is already happening in Salt Lake City, as apartment buildings appear seemingly overnight on 400 S., South Temple, State Street and 300 W. These apartment buildings are averaging upwards of $1000 for one-bedroom units, which is unaffordable for the working class. New housing developments will force Tina Balderrama, a hardworking nurse living on Salt Lake City’s northwest side, out of her home. In an interview with The Daily Utah Chronicle, she mentioned that her brother and his family were displaced first, and after they moved in with her, they were notified by the city that the property they lived upon was scheduled for demolition. By the end of March, Balderrama and her family must find another place to live. Balderrama expressed her frustration with the new developers’ lack of understanding and the city council’s lack of empathy. She wants action to be taken because “it’s [gentrification] like a domino effect all over the city.”

Currently, Salt Lake City and Utah’s government have claimed that they are making strides towards affordable housing, but their actions have shown otherwise. The Utah legislature recently passed S.B. 164, “Utah Housing Affordability Amendments,” which allows cities to give land to developers and put money upfront for housing projects, but only after the clause that required private developers to include affordable homes in their developments were cut. Additionally, of the $35 million proposed for addressing Utah’s housing crisis, only $10 million was funded, none of which will be for rental assistance. Our state and city need to put their money where their mouths are in order to create change. At a personal level, Balderrama claimed that the city was too busy pointing fingers at each other and playing the blame game to create solutions for her family and others who were in similar situations.

Salt Lake City can solve the housing crisis and combat gentrification by creating a multifaceted solution that addresses the concerns of those facing displacement. The telltale signs of a neighborhood on the gentrification “chopping block” are in close proximity to transit stations and downtown hubs. We must evaluate which places are vulnerable and create policies and programs to allocate resources to these places. Currently, Salt Lake City’s housing policy states that if housing units are demolished, the new development must have the same number of new units. However, it doesn’t give any restrictions on pricing. Affordable housing and below-market pricing for lower-income residents are severely lacking in housing policy, and it must be explicitly stated to protect vulnerable communities. More specifically, if the city plans on rezoning a certain area, it should draw up a contract with the current residents based upon equitable conditions and community concerns. Lastly, there needs to be a robust network of policymakers, lawyers, landlords and developers that will prioritize explicit provisions for affordable housing in new zoning projects.

As a college student, the housing crisis and gentrification are extremely pertinent to our communities and future. We want to live in a place that is affordable, equitable and supports the most vulnerable people in our city. Balderrama stated that our generation is the future politicians and lawmakers that will be changing this city — we must use our voices and positions as students to hold our city accountable to the future we want to see.

John Hedberg • Apr 20, 2021 at 5:22 am

Gentrification is, in essence, a word which defines an increase in an area’s diversity, not a decrease. Diversity and inclusiveness enrich an area, and not just economically, but why not start there?

Rising property values brings in more shopping options to eliminate current “food deserts”. It occurs around transportation hubs set deliberately, so families and singles with roommates can rent affordably while getting to work, to school, and lowering our carbon footprint. That’s a carefully planned win-win for everybody. Very importantly, it almost always improves K-12 education in the area, which now has additional funding for first-class schools and teachers. In almost every way, “gentrification” improves the lives of nearly everyone in the neighborhood, as higher tax revenues bring in better private and public services.

Are there people like you and me who need to double and triple up in new apartments? Absolutely. My first few years in Salt Lake, I enjoyed meeting roommates from around the country and around the world (Venezuela, Kenya, Honduras, Argentina, Mexico). Elbows were tight, like dollars, but we had a lot of fun in between work and study. I couldn’t afford a car, but my roommates and I could always find a way to get anywhere using Salt Lake’s superb UTA, which is far far better than many big cities make do with, especially if you bring a bike with you.

My heart does anything but bleed for neighborhoods being “gentrified”. Again, it means by definition they’re becoming more diverse, usually more inclusive if my roommates were any indication, local education and green transportation became better, and disadvantaged folks of all stripes suddenly didn’t have to travel so far for critical services like food, health care, or public safety. All these things flowed in.

“Gentrification” is not a social justice issue. In practice, as I’ve seen and lived it here in Salt Lake, it’s actually a solution, at least for those folks who are stable enough to attract roommates from all over the map. For those who haven’t achieved that stability yet, who may have chronic health problems, mental health challenges, and addiction issues, it’s always been hard to find housing in any neighborhood if you have a hard time meeting a lease month to month or a job week to week. Even then, good roommates in abundant numbers who are brought in by “gentrification” make that an easier prospect, simply because there are so many more new options. It’s not perfect, but generally speaking, when new housing rises, so do available resources both human, cultural, and financial.

That said, most at-risk adults definitely need increased & adequate engagement by social work, addiction resources, and critical health networks, and all of these would be helped by additional affordable housing: the state is apparently terrified of creating permanent generational tenements like previous growing cities have, so they’re trying to figure out a more dispersed and decentralized approach, like a toddler learning to walk for the first time: it’s a little messy!

With Love,

J Hedberg

Nikkole • Nov 14, 2021 at 1:27 pm

I enjoyed reading your comment, though quite lengthy. You failed to comment on the many displaced families, students, disabled and elderly who are stable enough to attract roommates, but didn’t need to. Those inhabitants are now displaced at no fault of their own. Are they just expected to take one for the team?