Soter: Emotional Abuse is Domestic Violence Too

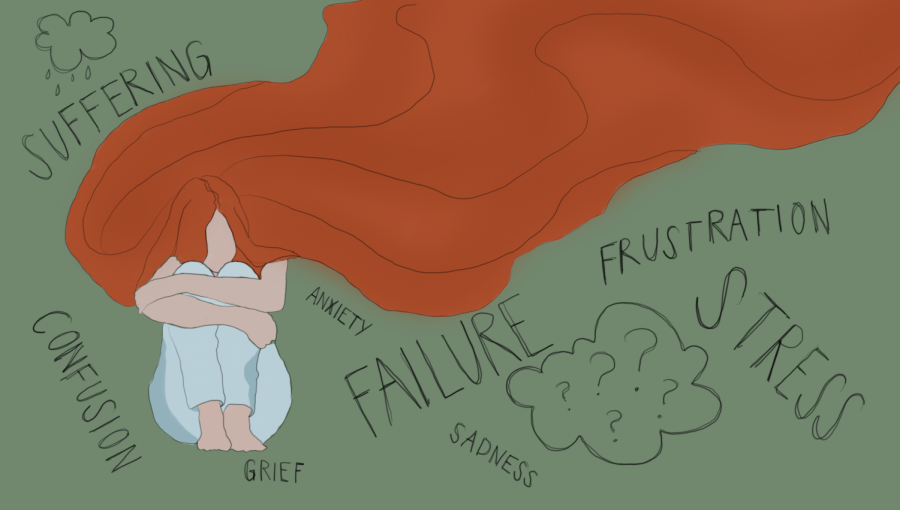

(Graphic by Storey McDonald | The Daily Utah Chronicle)

October 29, 2021

“MAID” on Netflix follows a struggling mom who leaves her emotionally abusive boyfriend to keep her and her daughter safe. Watching her struggle to get a roof over her daughter’s head and food on her table is distressing. But, after just a few episodes, it’s clear that watching her go back to her partner would be worse. Even still, in the eyes of Utah’s law, that mother wasn’t experiencing domestic violence, just a side-effect of it. That side-effect is emotional abuse.

Utah has done good things to reduce domestic violence throughout the state, but there is more to do. Bringing emotional abuse into the conversation on a larger scale is the place to start, and implementing legislation that requires LAP (lethality assessment program) is the way to ensure it gets done.

When talking to Liz Sollis, the communication consultant at the Utah Domestic Violence Coalition, the reality of emotional abuse set in. “I can tell you that domestic violence victims will sometimes forget about physical injuries they’ve experienced. I had a person say to me, ‘I forgot that caused my miscarriage.’ But they remember all the horrible things that they tell them forever. Those are scars that stay put.”

Our society thinks because emotional abuse doesn’t leave visible scars it doesn’t exist, but this is far from the truth. Emotional abuse can lead to many mental struggles. PTSD, depression and anxiety are some short and long-term effects emotionally abused individuals may face. Some researchers even believe that emotional abuse can contribute to other physical ailments like chronic fatigue syndrome and fibromyalgia. Sollis said, “For those people who have been berated day after day, it takes a toll emotionally on their confidence. And when they get out it could impact their ability to have positive relations with other people because it’s just been so embedded into their mindset that they’re the problem.”

But beyond the very real physical ailments emotional abuse can trigger, emotional abuse often is the precursor to physical abuse. “Before they bite, they bark. Before they hit you, they hit near you. Next time, it was going to be your face, and you know that,” says Aimee Carrero in the second episode of “MAID” and she’s right. The best preventative action to physical violence is actively working to address emotional violence. “We would hope that people get to us before it gets to that level, because once it gets to that level, then you’re actually experiencing physical violence or threats of it,” says Sollis.

In Utah, domestic violence is defined as, “any criminal offense involving violence or physical harm or threat of violence or physical harm, or any attempt, conspiracy, or solicitation to commit a criminal offense involving violence or physical harm when committed by one cohabitant against another.” And while this definition says nothing about the impact of emotional abuse on the human psyche, Sollis makes the point that including emotional abuse in that definition might not be the most productive approach.

“That type of behavior can happen anywhere. In many ways that could be why it’s not in legislation. It’s just an unfortunate human behavior made even more unfortunate in really unhealthy relationships.” On the other hand, LAP has proven to be productive, which is why it should be mandated by both law enforcement and healthcare providers across the state.

In 2016, LAP was implemented in our state by the Utah Domestic Violence Coalition and is based on the Maryland Model. The assessment consists of 11 questions that “will help to guide whether or not that person is at great risk.” Currently, the assessment is given out by multiple agencies across the state — the University of Utah is one of them. As of June of this year it was reported that 21,804 LAP screenings had been distributed since the program’s establishment.

The next step is to pair an agency with a local victim service provider. Once the alignment between the agency and provider is set in place, people within the agencies receive “additional training on domestic violence, awareness, intervention and response,” along with better connections. This alliance is particularly important for police departments because “there were times in the past when, because of the need to protect victims, service providers weren’t as connected with law enforcement.”

While the way LAP functions is beneficial, taking the program a step further could reduce domestic violence and emotional abuse substantially. “The 11 questions can be little bit more specific. They get into the deeper components.” If the state implemented LAP screenings at every healthcare appointment and every time law enforcement or other first responders were called, more people would be asked, required to answer in a safe way and given the resources depending on their needs.

Sollis said that another way to combat emotional abuse is to be aware of its signs for those in relationships or those observing relationships. For those in a relationship, signs of emotional abuse can look like threatening physical harm, withholding sex or other punishments like silent treatments. For those observing relationships, it can be harder to detect emotional abuse from the outside. “If there’s any abuse happening, most of us are never going to see. It’s called domestic violence because it takes place behind closed doors.”

That said, Sollis said there are things to look out for: “somebody who’s withdrawn, who is not confident, who is very emotional, meaning they could just cry on a dime as you’re talking to them.” Awareness of emotional abuse is especially important in Utah because of the state’s mandated reporter statute that requires anyone over the age of 18 to report any suspected abuse for both children and adults.

But most important of all, as Sollis said “everyone, everywhere, no matter who they’re engaging with, be kind. Think twice before you say things. You have no idea how your snarky remark could negatively impact somebody else’s life.”

If you or someone you know is experiencing abuse, whether it be emotional, physical or otherwise, call the domestic violence hotline: 1.800.799.SAFE.