University System of Georgia Threatens Tenure, Leaves Academia Uncertain

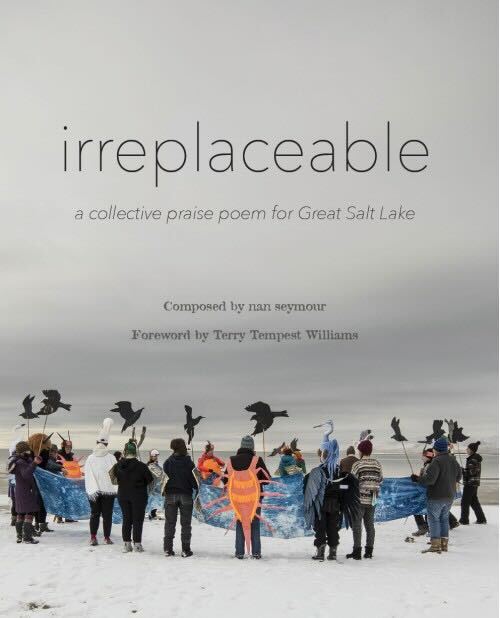

(Graphic by Piper Armstrong | The Daily Utah Chronicle)

December 16, 2021

Tenure safeguards academic freedom and provides the conditions for faculty to pursue research and innovation, free from corporate or political pressure. Recently, however, tenure has become the center of a heated debate in the academic world after Georgia’s public university system changed its process for reviewing and firing professors whose tenured status has long protected them.

On Oct. 13, 2021, the Board of Regents of the University System of Georgia gave its universities the power to fire tenured professors without additional faculty input. In the past, the process for removing tenured professors at UGS included a peer review process with other faculty. However, their 19-member board unanimously approved this new policy allowing termination after failing two consecutive annual reviews. These reviews serve as their objective measure of all faculty in several key areas: evaluation of instruction, student success activities, research/scholarship, and service as is appropriate to the faculty member’s institution, school or college, department.

This new policy by the UGS is the first of its kind and has proven divisive among academics.

“Tenure is a process that tenure-line faculty go through to establish themselves as scholars in their fields and as members of academic communities,” said Jennifer Andrus, associate professor of Writing and Rhetoric at the University of Utah and member of the University Promotion and Tenure Advisory Committee. “Once you go through tenure, you have certain rights and privileges that let you have more flexibility with how you create your career.”

Andrus said tenure is not about protection from being fired, bur rather about faculty-shared governance.

“It’s about being a member of a community that values scholarship, teaching and service, especially scholarship that helps the field and the department grow,” Andrus said.

In regards to faculty retention at the U, Andrus said there are checks every year where tenured faculty write a self-report on what they have accomplished.

“It is hard to fail very many of those reviews and lose your job,” Andrus said. “Before that, you would get called into the principal’s office and go through many checks-and-balances before you would be let go from a tenured position.”

Yet, this new policy by UGS has left some students wishing to pursue academia uncertain about their future.

“I actually find UGS’ policy very encouraging,” said Marina Gerton, a third-year undergraduate student at the U and member of the Undergraduate Student Advisory Committee for the Physics Department. “Having safeguards in place that ensure faculty are fulfilling their roles is pretty important because there is a fine line in academia between intellectual freedom and doing absolutely anything you want. I think holding faculty accountable is great. This would be a very positive thing for me as well because I could get constructive feedback on how I could improve as a faculty member.”

However, Gerton said it is difficult to say what the UGS policy means for the future of academia.

“I understand that this is a push for an objective method that determines faculty promotion and retention, although it’s really not one,” Gerton said. “You know, the idea behind creating an objective method while using survey data is not ‘objective,’ so I think that it is a bit of a difficult issue. I would be curious to see how this plays out in the next few years with the faculty at UGA, which is not to say that I want an experiment to be happening at the expense of people’s livelihoods.”

With these new changes to tenure, the labor economics of academia has reached an inflection point.

“The academic labor market is rather narrow and specific when compared to other labor markets,” said Thomas Maloney, labor economist and professor at the U. “Getting a Ph.D. aligns people to specific employers, and from there it’s a narrow track. While professionals like doctors and lawyers might have the ability to exercise optionality for where they work … academics have relatively fewer options and have a very particular kind of work.”

Maloney said there is an oversupply of academic labor because the labor supply is not “responsive to demand in academia.”

“However, the academic labor market does respond to other factors: creative freedom and academic liberty, to name a few,” Maloney said. “Tenure is one of those factors, and it attracts people to the academic labor market. It is the promise of due process within an institution and offers a great deal of stability once you get it. However, tenure is only relevant for a minority of academics — most teaching staff in universities are on the ‘career path’ or are adjunct professors.”

With UGS providing the first serious threat to academic tenure in recent memory, Maloney believes the implications of this threat are less clear.

“Tenure certainly offsets the risks involved with being an academic,” Maloney said. “Having to move and find positions elsewhere is costly, and tenure protects established academics from that. However, it is not a lifetime guarantee. Tenure does not protect academics from policy or department closures. During COVID-19, for example, many tenured professors lost their jobs because of department closures.”

Maloney said while the majority of academics would not be impacted by this new policy, it does make academia jobs less attractive.

“So, it could affect the supply of the labor market,” Maloney said. “But as I said, there is currently an oversupply. In the long run, this policy might sort things like this out, but it is hard to say.”