Lezaic: Examine the Prevalence of Exoticism in Tattoo Designs

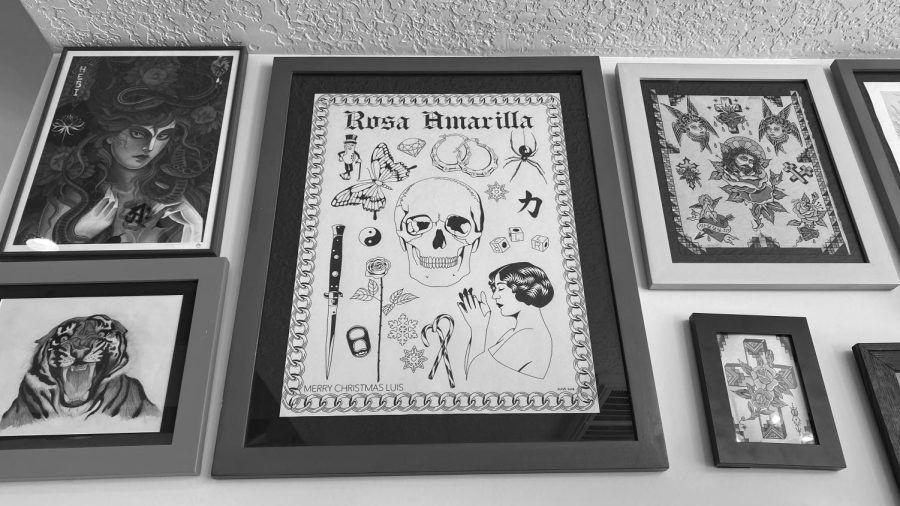

Different prints of tattoos in the Yellow Rose tattoo shop in Salt Lake City, Utah on Sept 9, 2022. (Photo by Jonathan Wang | The Daily Utah Chronicle)

September 12, 2022

If the world of tattoos interests you, then you’ve likely seen your fair share of questionable designs. And in some cases, questionable is an understatement. When artists and clients alike opt for designs that exoticize different cultures, their tattoos can pose harm to entire communities. We need to understand the imperialist history behind the use of such depictions and the racial implications of inking them onto our bodies.

History of Exoticism in Art

Art influences culture and human behavior in more ways than we give it credit for. Before travel became more feasible for average people, they depended on artists’ and storytellers’ depictions of other cultures to form their impressions of the outside world.

Imperialists took advantage of this fact, depicting those they viewed as outsiders as backwards, uncivilized and conquerable. Painting such depictions served their vested interest in more easily stealing foreign resources. An entire movement emerged in the Western art world of the 1800s where artists called Orientalists portrayed North African, Middle Eastern and Asian people in hypersexualized, submissive and mystical scenes. More often than not, these artists had never even been to the regions they tried to represent in their work. Their baseless misrepresentations of people contributed to fueling and justifying racist, imperialist actions.

Nancy Demerdash, an Albion College professor with a focus in North African and Middle Eastern art writes, “In Europe, trends of cultural appropriation included a consumerist ‘taste’ for materials and objects, like porcelain, textiles, fashion, and carpets, from the Middle East and Asia. … The ability of Europeans to purchase and own these materials, to some extent confirmed imperial influence in those areas.” What purchase is more permanent and proprietary than a tattoo?

Exoticism in Tattooing

This behavior never stopped. Our society continues to depend on the stratification and exploitation it was founded on, so it continues to produce justifications. We can see these justifications working in the world of tattoos.

Though tattooing practices had been present in many pre-colonial societies for a long time, they started gaining popularity in Europe when colonialists returned with tattooing knowledge. As tattoos started becoming mainstream in the West, so did designs that negatively portrayed the regions those styles came from.

While some negative portrayals are outright racist caricatures of people or hate symbols, others fly under the radar more easily. Appropriated imagery, for instance, is common within different subcultures. In the new-age spiritual scene, you see white women putting Hindu, Buddhist and Islamic designs on their bodies. Self-proclaimed punks get edgy American Traditional designs of sexualized Geisha or Indigenous people in headdresses. Tourists pay for random Chinese characters that they can flaunt to their friends when they return home. Surfer bros get designs that are deeply significant to Polynesian cultures. Recently, I’ve noticed a rise in creeps who put images of scantily dressed Japanese schoolgirls on themselves.

Each of these subcultures use tattoos to subvert or spite oppressive Western expectations. But in the process of trying to signal how different and exotic they are, they fall right in line with the Western narrative. That is, they juxtapose other cultures as intrinsically opposite to the West. Disrespecting and minimizing other cultures doesn’t make you cool — it only makes you part of a larger problem.

Real Consequences

Creating and promoting such insensitive images of cultural groups harms the people who are a part of them. Tattooing pictures of submissively posed Asian women, for example, replicates attitudes that coincide with the high rates of sexual violence against Asian women in the U.S. Choosing to permanently wear images that disrespect Indigenous traditions certainly does nothing to stop the violence against them either, especially when The American Indian Religious Freedom Act wasn’t passed until 1978.

Paying for these tattoos as a white person is not appreciating culture, despite what some may claim. Likewise, profiting off of creating these designs as a white person disrespects that culture. Without any real understanding or connection to what they’re creating, white artists pull inspiration from narratives that are likely false and harmful. Even if the portrayal is technically accurate, the action of duplicating what you don’t understand speaks for itself as exoticizing.

Tattoos are fun and a chance for the exploration of aesthetics. However, when we fall into step with narratives that seek to aestheticize entire cultures as mystical, sexual or barbaric, we promote behaviors that dehumanize entire groups of people. Such dehumanization makes it easier to allow hatred, violence and exploitation, as it has in the past.

Criticizing these tattoos may seem like a reach to some people, but the sentiments behind them are a symptom of a much larger racist issue. If you can’t recognize that, then perhaps you need to analyze your privilege.

Xiao Yang • Sep 15, 2022 at 1:42 pm

I appreciate this article and have been frustrated about this exact topic for years. I’ve seen my fair share of badly tattooed Chinese characters and I can always tell when they’ve been tattooed by someone who doesn’t speak or write the language. Because they always look bad.