Advocacy Group Leads the Way to Make Salt Lake Streets Safer for Pedestrians and Cyclists

(Design by Claire Peterson | The Daily Utah Chronicle)

April 12, 2023

In the fall of 2019, Taylor Anderson and a couple of friends decided they had to take some sort of bigger action to advocate for the dangerous car-centric streets of Salt Lake City to become safer for pedestrians and bikers.

There was a similar sentiment they repeatedly heard from people in the community — both from people who grew up living here and ones who didn’t.

“Whether they were trying to walk around, take transit or ride a bike, they just felt like they were going to get run over and killed,” Anderson said.

Through reading books by urban and transportation planners and hearing from the community, Anderson had a realization that policy decisions, big and small, ultimately decide how safe the streets are for people not driving a car.

“[I asked myself], ‘What can we do to change those decisions and build a voice of people that already felt the same way?’” Anderson said. “Whether they had that realization or not, they also felt like the streets in Salt Lake City are dangerous and wanted to do something about it.”

With that, Sweet Streets, a group that educates and advocates for safer roads and public spaces, was born.

20 is Plenty

According to Sweet Streets’ SLC Traffic Violence map, which gathers deaths and injuries from traffic incidents, there were 21 fatalities on Salt Lake City’s roads in 2022, which includes many pedestrians and cyclists. There have been three fatalities in 2023 so far.

Sweet Streets has several campaigns they advocate for, including 20 is Plenty for Salt Lake City, which called on the City Council to prioritize safety by adopting a default 20 mph speed limit on most city streets. Anderson said the concept initially started in Bristol, England, but versions of it have been advocated for across Europe and the U.S.

Starting in early 2021, Sweet Streets started an online petition to collect signatures from people in the community to voice their support to have “some public-facing way to show the city how many thousands of people are calling for this change,” Anderson said. They also distributed over 600 signs around the city and created the SLC Traffic Violence map to build the case that streets in the city aren’t safe.

In March 2022, Sweet Streets made a presentation to the City Council and in the straw poll vote — an unofficial vote to gauge the majority opinion on an issue — everyone voted to move forward with the policy change.

“But I still thought that wasn’t a done deal,” Anderson said. “I thought there would be public meetings, just more battles ahead to try to convince skeptics because there were plenty of skeptics around the point of doing this.”

In May 2022, the Salt Lake City Council voted unanimously to lower the speed limit from 25 mph to 20 on about 420 miles, or 70%, of streets in the city.

What Anderson thought was going to be a five-year process ended up taking just over a year, but he said 20 is Plenty was step one in a long series of campaigns.

Street Design and Neighborhood Byways

Anderson said it’s important to realize that research shows that the design of the street, more than speed limits, dictates the speed people feel comfortable driving their cars.

“That includes everything from whether there are trees on the side of the street, what lane width the street is, whether there are speed humps, speed tables or raised crosswalks,” Anderson said.

He added the problem is cities have been designed to be car-centric for about 100 years now — even longer for Salt Lake, because the roads were originally designed to be large enough to turn around a team of oxen.

“So that’s kind of a built-in problem, but also a built-in opportunity — because when we have wide streets, that’s actually just a lot of public realm that we can work with,” Anderson said.

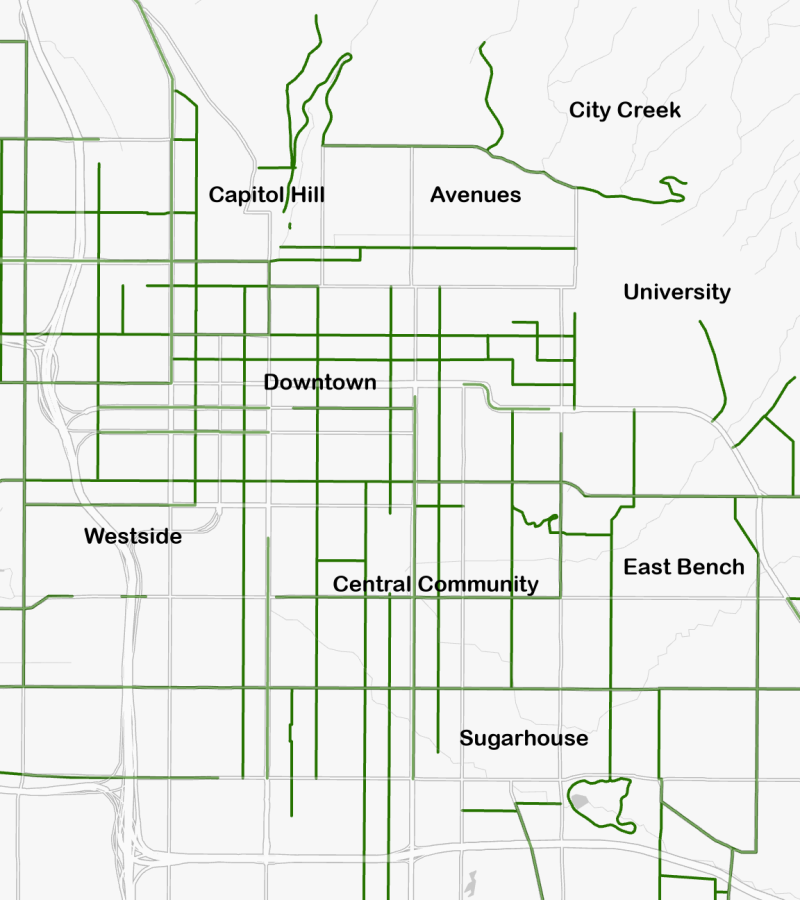

Another important campaign for Sweet Streets is Neighborhood Byway 2025, which calls on Salt Lake to fund and build a network of neighborhood byways — low-traffic, low-speed streets — by 2025.

The byways often include treatments to discourage through traffic and elements to promote slow, safe local traffic speeds, including speed tables and speed bumps, according to Sweet Streets.

“[It’s] a place that you might feel comfortable biking with a kid, a grandparent or with somebody that’s not comfortable riding among high-speed traffic,” Anderson said.

In Salt Lake’s 2015 Bike-Ped Master Plan, they recommended building a network of neighborhood byways that totaled 68 miles. The city said its goal is to complete 10 byways by 2025, according to Anderson.

“A proposed network of ‘neighborhood byways’ taps quiet neighborhood streets and formalizes them into transportation corridors designed to crisscross the city and link to key destinations including neighborhood retail areas and corridors, parks, schools and transit stations,” the plan reads.

So far, only one has been created, according to Sweet Streets.

In Salt Lake City Mayor Erin Mendenhall’s plan for 2023, she made a goal to “finish design and/or construction of at least four neighborhood byways throughout the city.”

Anderson said to hold the city accountable to these plans and recommendations, Sweet Streets is trying to identify people that would lead the process.

“To let community councils know that the city has a plan and we want that plan to be carried out,” he said. “Basically, build pressure on the city to identify sources of funding to build these byways.”

An additional campaign by Sweet Streets is the 200 South Bus Corridor, another city-led effort, that would create the city’s “first bus-only lane along a high-frequency route running from the University of Utah to 600 West every 15 minutes.”

SLC to Join Vision Zero Network

In a Jan. 11 statement, Mayor Mendenhall announced Salt Lake will be the first city in the state to join the Vision Zero Network, a “national strategy to eliminate all traffic fatalities and severe injuries on City streets while increasing safe, healthy, equitable mobility for all.” The mayor set a goal to achieve zero traffic fatalities and serious traffic injuries by 2035.

Jon Larsen, SLC’s transportation division director, said Salt Lake isn’t officially a Vision Zero city until a few more requirements are met. The first step was getting a declaration from the mayor.

“The value of that declaration is it provides a unified vision across the city,” Larsen said. “It’s not just a mandate to the transportation division, but everyone who does work in the right of way.”

Another step is having a guiding Vision Zero action plan that lays out specific goals. The transportation division is working to do this with the Wasatch Front Regional Council, which received a federal grant recently to develop a regional action plan, according to Larsen.

“So we’ll work to ensure that checks all the boxes for becoming a Vision Zero action plan,” Larsen said. “Every city in the region could benefit from this [because] it will make it easier for them to make the leap to join us in being Vision Zero cities.”

In addition, the Safe Streets Task Force has become the Vision Zero Task Force which identifies areas of the city where intervention might be necessary to prevent future crashes, injuries and deaths. Larsen said they will also hold the transportation division accountable for implementing the action plan.

Dave Iltis, Cycling Utah editor and publisher, wrote an editorial last December that called on Mayor Mendenhall and the Utah Department of Transportation to immediately adopt Vision Zero.

“What I hope it does is [cause] every single decision in transportation that’s made by Salt Lake City to be made with the goal in mind of eliminating traffic fatalities and severe injuries,” Iltis said. “And if they have that in mind, that is going to lead them to make the right choices for keeping all road users safe.”

Iltis added this could apply to everything from when the city is reconstructing or building a new road to retiming a traffic light. With a large number of deaths on Salt Lake’s roads in the last couple of years, Iltis said he believes the city saw this commitment to Vision Zero as something they had to do.

“It’s very sad that it sometimes takes tragedies to have good things come out of that,” he said.

Larsen said they have a good shot at being able to check all the boxes to officially become a Vision Zero city by the end of this year, but it might take until early 2024.

“We’re well on our way and this is a really exciting moment,” Larsen said. “Hopefully in the not too distant future, we’ll look back and say, ‘2023 was that turning point where we finally, as a city, decided it was worth the tradeoff to save lives, even if it means slowing cars down a little bit and maybe adding a little bit of inconvenience to traveling in the city.'”

Long Road Ahead

In the past few years, Anderson said he feels great about the positive steps taken forward with 20 is Plenty and Salt Lake planning to become a Vision Zero city, but acknowledged there’s a lot of work to do.

“You don’t become a car city overnight and you don’t undo that overnight,” Anderson said. “It takes a lot of time. It takes a lot of people making conscious decisions.”

Anderson believes people who live in Salt Lake have hit that point where they’re over the city being built to be car-centric and benefitting people driving in from the suburbs in the morning and back out at five.

“I think we’ve seen a change in the city in the last couple of years that residents are sick of that mentality and they’re ready to make their voices heard to make a change,” Anderson said. “So I think I’m pleased with the direction that things are going. I would always like for it to happen faster, but I’m really glad that things are moving in the right direction.”