‘Possessing Polynesians’ Unpacks Settler Colonialism Amongst Native Hawaiians

July 6, 2023

A new book from Associate Professor of History and Gender Studies at the University of Utah Maile Arvin looks at the history of white settler colonialism in Polynesia and Oceania.

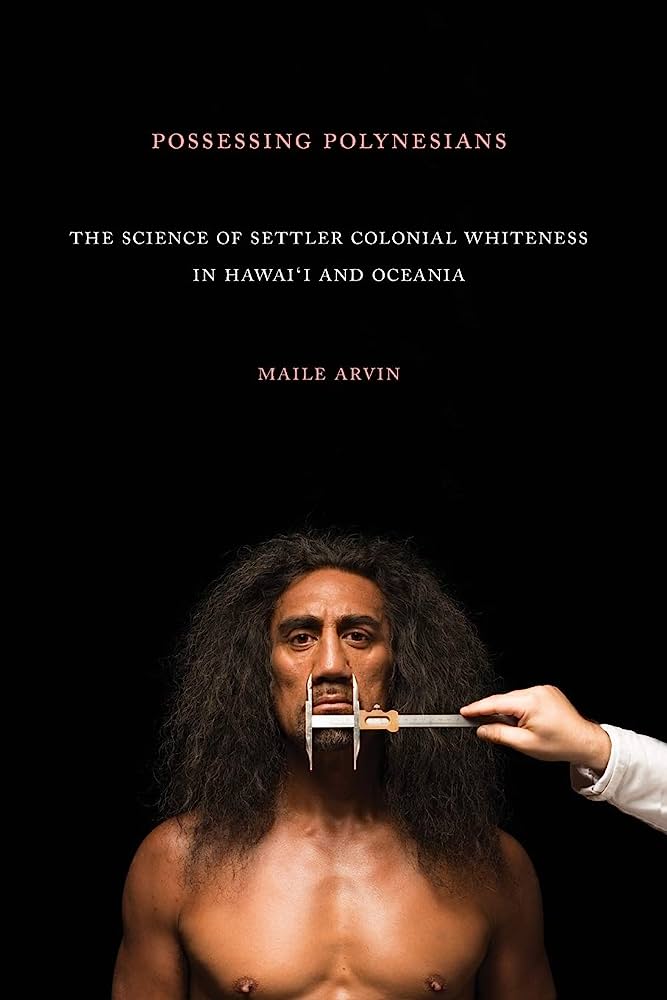

Titled “Possessing Polynesians: The Science of Settler Colonial Whiteness in Hawai’i and Oceania,” it includes some of the earliest findings from social scientists who tried to identify the origins of Polynesians.

“‘Possessing Polynesians”‘ is not set to reveal truths about Polynesians per se, but to expose the foundations of settler colonial power,” Arvin said. “It is more of a detailed genealogy of colonization in Polynesia and Oceania.”

In the context of this colonial genealogy, the book discusses social scientist Louis Sullivan. Sullivan, among other people in his field, referred to Polynesian people as “almost white.”

An example of Sullivan’s work can be found on page 85 of Arvin’s book. Sullivan captions an image of a Polynesian with, “In Him Nature Seems Just to Have Missed Producing a Caucasian.”

Arvin explained that claiming the Polynesian race to be “almost white” had no benefits for Polynesians but aided colonization in places like Hawaii. She called this ideology “possession through whiteness,” where white people claimed things they did not have a right to.

Arvin explained that ideologies from people like Sullivan helped to create laws like the 1920 Hawaiian Homes Commission Act, which hinders Hawaiians from obtaining a homestead.

“The HHCA forces Hawaiian to prove their Nativeness by a blood quantum test,” Arvin said.

The Indigenous Foundation defines blood quantum as “a strategy used by the government and tribes to authenticate the amount of ‘Native blood’ a person has by tracing individual and group ancestry.”

Arvin explained the problem with a blood quantum test is that most Hawaiian families believe they should be able to decide who in their family is “Native” by Hawaiian tradition and ancestry, not by how much “Hawaiian blood” they have.

Arvin is Native Hawaiian from her mother’s side. Her mother currently lives on a homestead in Waimānalo, passed down from Arvin’s grandfather.

The HHCA causes extreme tension between families and the state government because Native Hawaiians, like some in Arvin’s family, would not be able to meet the 50% blood quantum to prove they’re “Native Hawaiian.”

Another point Arvin addressed is Hawaii being known as a “melting pot,” where Hawaiians face no discrimination. She said early white settlers wanted to take over and gain power and wealth in Hawaii.

“White settlers became really invested in the idea that Native Hawaiians would mix with the white people and therefore there wouldn’t be differences between them, therefore white people would have as much of a right to the land as Hawaiians,” Arvin said.

She added “Possessing Polynesians” aims to critique this idea of the melting pot by showing “how it comes out of the ideas of white people trying to claim ownership over the land.”

The cover of Arvin’s book is an illustration from Yuki Kihara‘s 2015 artwork “A Study of a Samoan Savage.”

“Kihara’s artwork shows a white man holding anthropometric tools to measure the nose of a Samoan man,” Arvin said. “These tools explicitly reference work like the work of Louis Sullivan.”

Samuelu Elisaia, a former football player for the Utes and Native Samoan, found the cover to be interesting and was left wanting to know more.

“As a Polynesian living in the mainland, I don’t hear too much about what’s going on in Hawaii, but the cover immediately makes me open up my eyes to be more in tune with what’s going on with our people,” Elisaia said.

Blood quantum requirements from the HHCA left Elisaia unphased and displeased.

“Nothing really surprised me about the blood quantum test but it is disappointing, using the ‘natural effects’ of colonization to keep Native people from owning their land is a bit upsetting,” Elisaia said.

Arvin is the director of the Pacific Island Studies program at the U. This program has obtained two Mellon Foundation grants to aid research.

Still, work is not finished at the U, Arvin said, but more positive changes are coming.

“The U is working to open a center for Pacific Islanders and Indigenous peoples,” Arvin said.

The foundation would help raise awareness for the minority of Pacific Islanders at the U.

Elisaia said he hopes this foundation helps the local Polynesian youth thinking about attending the U.

“I’m glad there are things happening and I hope the U continues to do more for the Polynesian youth, a lot of kids don’t even think past high school, they don’t believe it’s an option,” he said.