The Utah Museum of Fine Arts recently celebrated the opening of its new special exhibit “Tatau: Marks of Polynesia” with an opening event that took place on Aug. 12. Tatau the art of Samoan tattooing, is documented in photos, objects and video in the museum’s new exhibit.

Ancient Tattooing

“An indigenous art form with a continuous history that dates back 2,000 years, tatau has played a pivotal role in the preservation and propagation of Samoan culture,” reads the Japanese American National Museum’s website, from which the exhibit originated.

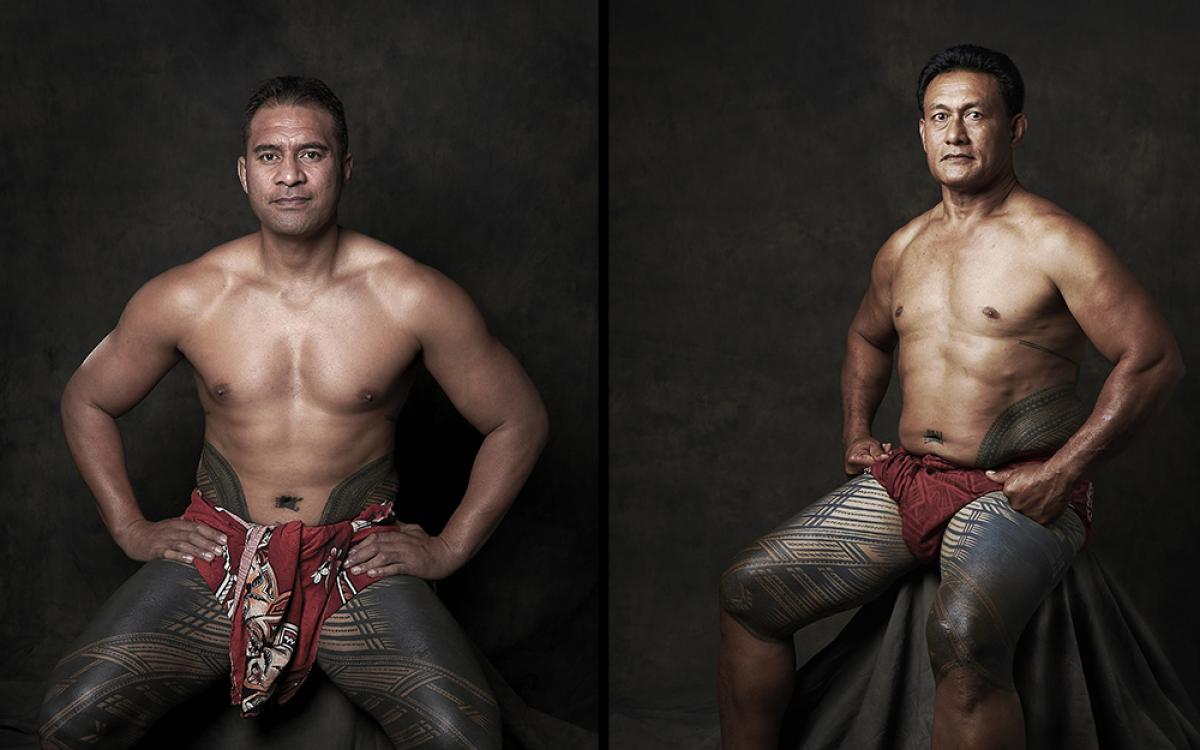

The tatau is a ritualistic Samoan practice where one is tattooed with traditional designs. Thus, giving a strengthened sense of national and personal identity. The tufuga tā tatau, or Samoan tattoo masters, hold high social status.

There are two traditional tatau designs, the pe’a, which is the traditional male tattoo, and the malu, the traditional female tattoo. Both designs are representations of the duties and roles the wearer of the tattoo holds.

“This ritual is critically important, considering the numerous attempts by missionaries and colonists to suppress cultural expressions like tattooing throughout the Pacific,” UMFA describes.

The exhibit specifically highlights the Sulu’ape family, who have been credited with reviving the practice of tatau. The tradition has since had influence around the world. Photos from the exhibit taken in the United States and New Zealand demonstrate the art form’s spread and adaptations.

‘Ava Ceremony

To celebrate the opening of the exhibit, UMFA invited Samoan leaders and members of the Sulu’ape family to take part in an ‘ava ceremony.

“The ‘ava ceremony is an ancient Samoan ritual that is performed at the beginning of all important services and gatherings,” reads a research essay written by Alyssa Melville and published by the Japanese American National Museum.

Observers packed around the balconies of UMFA’s Great Hall where the ceremony took place. Partakers of the ceremony bore traditional clothing as they sat around the sacred space where the ceremony took place.

As leaders took turns speaking throughout the ceremony, the ceremonial drink called ‘ava was being prepared. The drink is made from the ‘ava plant, and once it’s done being prepared it is served to guests in order of social rank.

“The power of this ritual comes from its great care and attention to detail. Every move made is very deliberate,” reads Melville’s essay.

The ritual was done in Somoan and ended with dancing as the exhibit opened to viewers.

Dances and Demonstrations

As viewers wandered through the newly open exhibit, UMFA also held a tatau demonstration, an art-making activity and several Polynesian dance performances. Food trucks serving Polynesian cuisine also lined the street in front of the museum.

The tatau demonstration was held in the museum’s auditorium, where observers were able to watch the traditional practice as it was taking place.

Dancers of all ages celebrated the event’s occasion in the Great Hall, cheered on by yells of encouragement. Much like tatau, traditional dancing was subject to attempted suppression by missionaries. Dancing at the exhibit’s opening event not only celebrated Polynesian practices and culture but also celebrated the fortitude of these traditions as they live today despite the efforts to subdue them.

“Tatau: Marks of Polynesia” will be open until December 30.