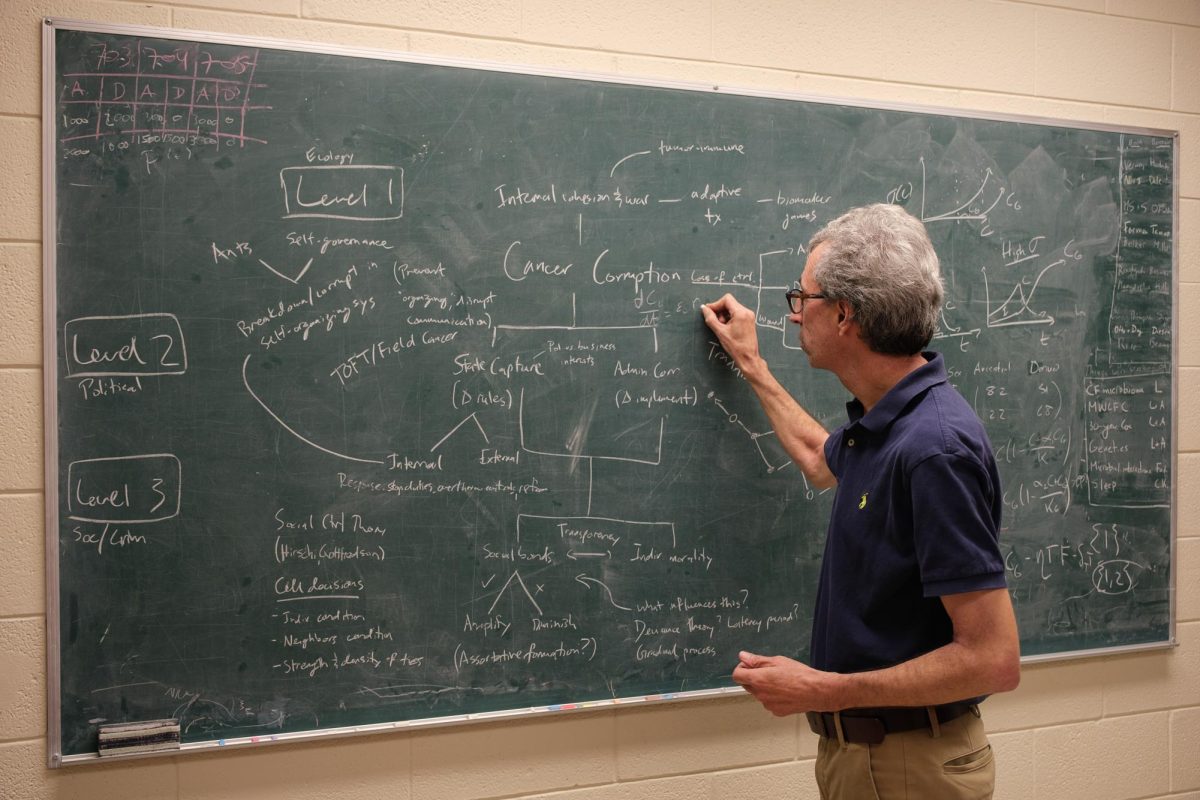

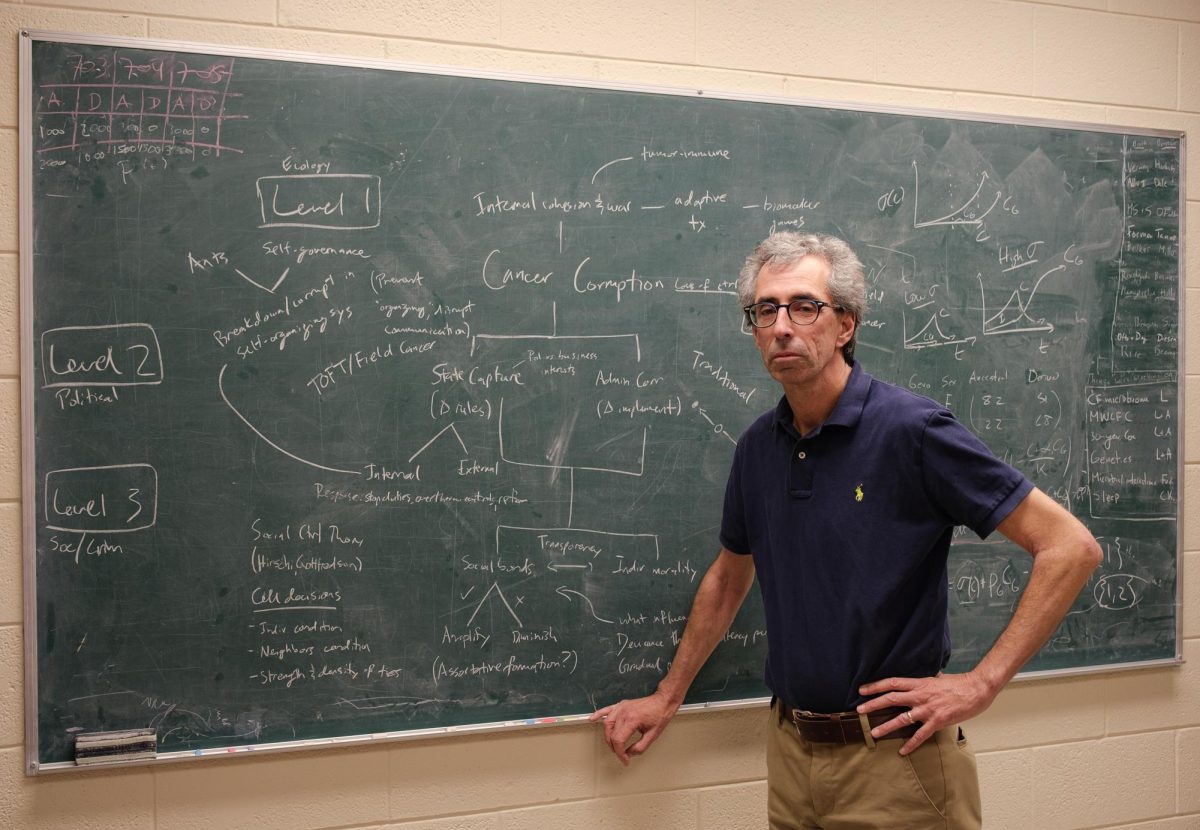

The University of Utah prides itself in its continual research in health and medicine. Especially when it comes to cancer research, the U is finding new ways to innovate. Fred Adler, director of the School of Biological Sciences at the U, and his cohort of bio-mathematicians are using mathematics to further develop cancer treatment and research.

Recently, Adler was praised by the U for his work with the Beckman Research Institute located in Duarte, California.

Adler is working with a group of bio-mathematicians at the U to use mathematical modeling to better understand reactions and results in cancer research. Adler said math has “many different roles in the world,” one of which includes “understanding the structure of the universe.”

“I, in some sense closer to physics, [use] mathematics to understand biology,” Adler said, “… our job is to use math to try to find some simplicity of its complexity.”

He added many people don’t understand how applicable math is in other scientific fields, such as biology.

“I think a lot of people just don’t know how powerful a tool mathematical thinking is for quantitative thinking,” he said. “In fact, it’s changed every field of biology.”

Adler has found success in using mathematics in his work. He said “The mathematical side has been combining mathematical models with experiments. … We like to see it as it’s like a microscope helps see the invisible.”

Jiyeon Park is one of Adler’s associates making strides in cancer research. Park is a second-year post-doctorate who finished her Ph.D. at the University of Southern California. A trained mathematician, she’s using math to help in cancer treatment.

Using mathematical models, Park said she is working with Adler to develop “optimal therapy schedules” for cancer patients.

These mathematical models help specialists understand what’s happening over time in cancer patients. Adler and his associates use applied mathematics to predict and understand biological responses to cancer treatments, and the modeling enables them to predict results more accurately.

“Maybe we can have some of the nice predictions over time about the cancer ecologies and once we can also model the therapy schedules together … then we can predict what’s going on in the future,” Park said. “And we can, you know, sort of in the coming weeks and nights, schedule immunotherapy or the chemotherapy.”

Their research is also being used to help the Food and Drug Administration figure out which drugs are the most effective.

“We study these kinds of drugs,” Park said. “We want to understand how it helps to boost a patient’s T-cells activities.” T-cells are a type of white blood cell that bolster and protect the body. They are an important part of the body’s defense against cancer.

Park is confident that applied mathematics can better cancer research.

“I’m starting to participate in a very practical area so that I can use or I can contribute to the field,” Park said. “Somehow in the future, I will help patients cure their disease.”

Montana Ferita is a math Ph.D. student at the U. She is also using applied mathematics in her research to look at what activates the human immune system.

Specifically, she’s doing work with natural killer cells. Discovered in 1975, NK cells destroy harmful cells, particularly cancer. Ferita said because they are “recently discovered, people don’t really know a lot about them.”

It is in situations like these that applied mathematics have been resourceful in solving complex biological problems.

“I’m using math models of different signaling parts what we know about NK cells to then try make predictions,” Ferita said. “If you have experimental data, and you can fit the model to that data set, we’re able to make other predictions about stuff.”

Ferita is optimistic in the ways that mathematics are going to be pushing research further.

Adler and his associates have been focused on attacking the cancer ecology. They are working on not just attacking the root of the cancer but attacking every cell that the cancer has touched. Their foundation in mathematics has changed the way experts approach cancer research.

“The next big breakthrough in cancer is not going to be that we come up with or a miracle like treatment,” Ferita said. “It’s going to be using what we already know better.”