The J. Willard Marriott Library recently debuted a digital exhibit: “A History of Special Collections,” an archival history of the Marriott Library’s archive division.

The exhibit details the Special Collections’ origins in 1850 with the founding of the University of Deseret, to the archive’s transition into the Marriott Library in 1968 and finally to the modern day.

Why the Exhibit Started

Lyuba Basin, rare books curator at the Marriott Library and co-curator of the digital exhibit, said the start of the COVID pandemic inspired the idea to archive the library’s history.

“There were a lot of retirements that happened during the pandemic,” Basin said. “When they leave, with them leaves an institutional history, and so you don’t have them available to go into their office and say, ‘Hey, do you remember what happened back then?’”

She said along with these departures came the desire to “secure that institutional history,” and the exhibit was born.

While the University of Utah has had a policy of archiving records since 1967, Basin said the methods of fulfilling that policy aren’t fully realized.

“As employees of the University of Utah, we are supposed to be archiving our work in this kind of way … but from what I’ve seen, there is no organizational method of how you go about that, or what you need to save,” she said.

What’s In the Exhibit

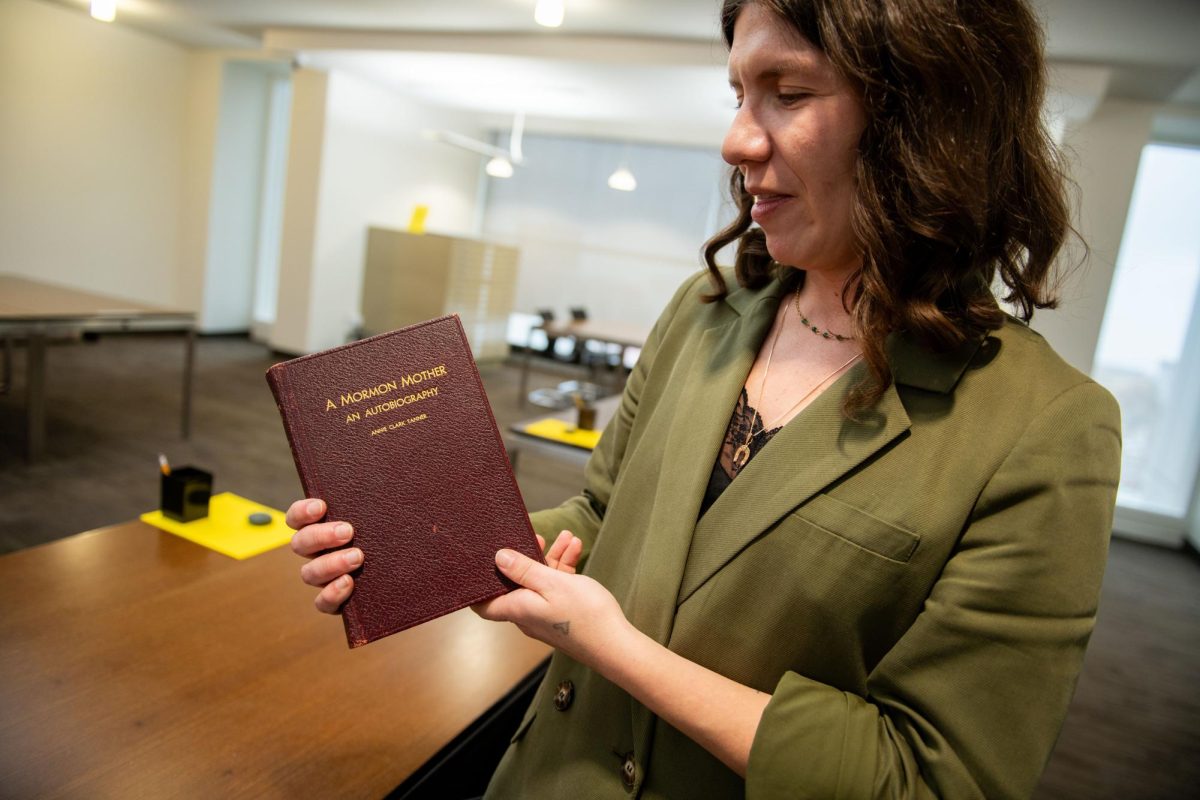

Some of the things displayed include “Special Collections Brochures,” which come from a collection of library budgets, reports, statistics and internal memos from 1965 to 2020. Also displayed are catalogs from the Utah Territorial Library and the University of Deseret Library from the nineteenth century.

Through these collections, the exhibit illustrates an expansive history of the archive.

In 1971, the archive changed its name to Special Collections. The name change was due in part to the merging of the archive with the Aziz S. Atiya Middle East Library founded in 1959 and its greater focus on rare books.

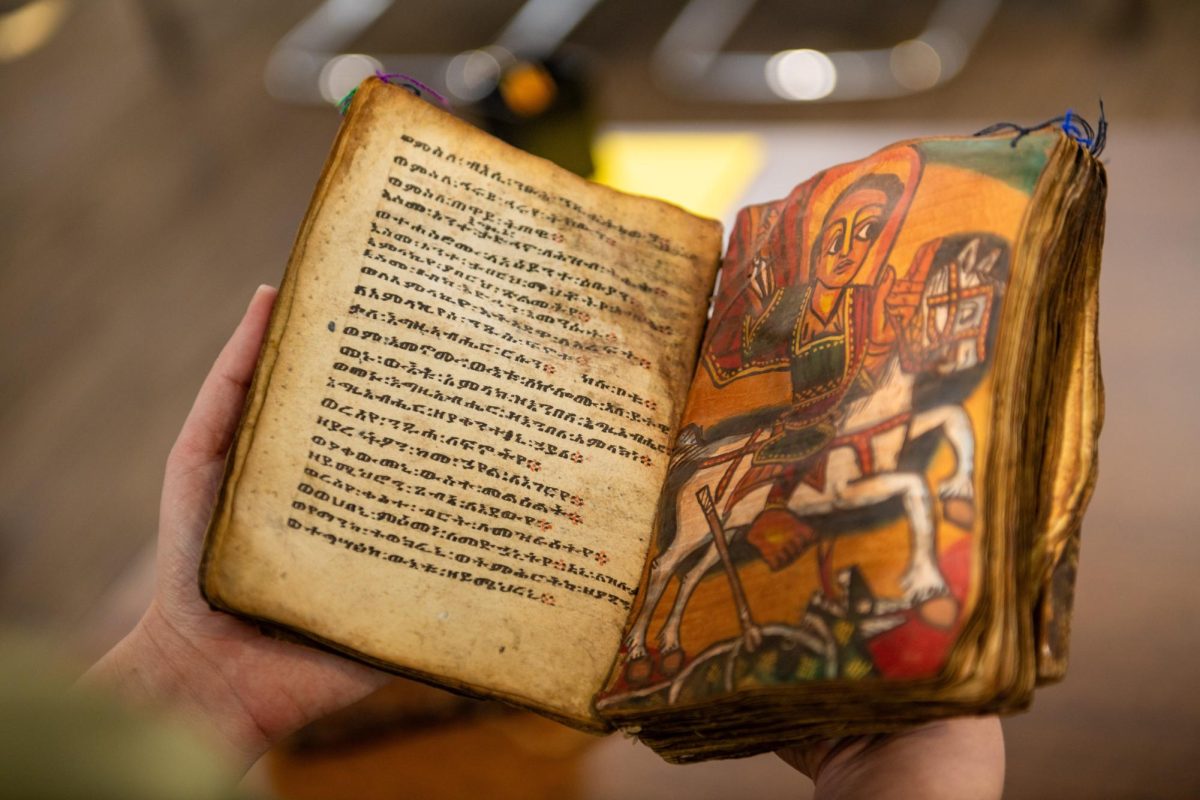

Among the Special Collections’ rich selection of rare books includes the Florentine Codex, translated from Aztec to English by anthropology professor Charles E. Dibble and anthropologist Arthur J.O. Anderson. Another notable book is the Ethiopian Codex, a manuscript written in Ge’ez, a Semitic language no longer spoken, but is still used for religious purposes by the Ethiopian Orthodox Church.

“We don’t have as much research resources to translate the Ethiopian Ge’ez language,” Basin said. “I’m going to be contacting the Ethiopian Tewahedo Church … to see if I can work with their community and to see if they have any interest in looking at our collection, working with the collection, translating the collection and identifying the pieces that we have.”

The exhibit also shows how the Manuscripts Department of Special Collections developed in the 1970s. Some of the manuscripts included are the Utah Pride Center records, and the Doris Duke oral history collection, which are transcripts of interviews with Native Americans conducted from 1966-1972. The transcripts are currently closed because they are under tribal review.

“We’re working with all of the different tribes represented to see what can be made available to the public, what needs to be restricted seasonally, [and] material that’s sacred and is only available to tribal members,” said Rachel Ernst, co-curator and reference librarian for special collections.

“A History of Special Collections” opened at the start of the spring semester, coinciding with the Book Arts Program offering a new major.