The Tanner Humanities Center at the University of Utah hosted a talk with Danielle Endres, professor of communication and director of the U’s Environmental Humanities program. Endres discussed her new book Nuclear Decolonization: Indigenous Resistance to High-Level Nuclear Waste Siting, which details the activism of the Western Shoshone, Southern Paiute and Goshute people against establishing nuclear waste repositories on Indigenous land.

Endres sat down with Logan Ray Gomez, an assistant professor of communication at the U. Enders began the discussion by saying she became interested in the anti-nuclear movement and Indigenous resistance movements in the 1970s due to the fear of nuclear war in the era and the occupation of Alcatraz Island.

“When I got to college … I got interested in uranium mining on native lands in the Southwest and Intermountain West regions. That began this multi-year kind of research into nuclear colonization,” she said.

Endres said nuclear colonization is a system of settler colonialism intersected with nuclear power that harms Indigenous people.

The discussion focused on the main argument of the book. Endres said the arguments in the book are not hers but were developed by Indigenous activists on the ground.

“It was really important for me in the book to de-center myself as the academic that came with the theory that could explain what was happening and to rather see that theory was being developed by the folks I was engaging with over time,” Endres said. “And so the main theoretical argument is me retelling and amplifying the theories of the folks I worked with.”

Endres talked about how her research shifted her views on academia. She stressed how she became less concerned with contributing a new theory and more about documenting events and collaborating with communities to tell those stories.

“Another thing that shifted was that I was seeing this movement had succeeded,” she said. “And if there were not communities of people that were coming together to archive and tell this story, that was a real loss.”

One of the events Endres covers in her book is the nuclear waste repository that was established on Yucca Mountain in 2002. After fierce resistance from the Shoshone people, Congress defunded the project in 2006 and it was later abandoned by the Barack Obama administration. After abandoning the project, the administration enacted a Blue Ribbon Commission on America’s Nuclear Future. The commission released a report in 2012 that recommended a consent-based siting for storing nuclear waste.

“This move to consent-based siting for nuclear waste is hugely important because it shifts the philosophy to say that communities need to be involved in decision-making from the very start and need to consent from the very beginning and then have a chance to pull out of that,” Enders said.

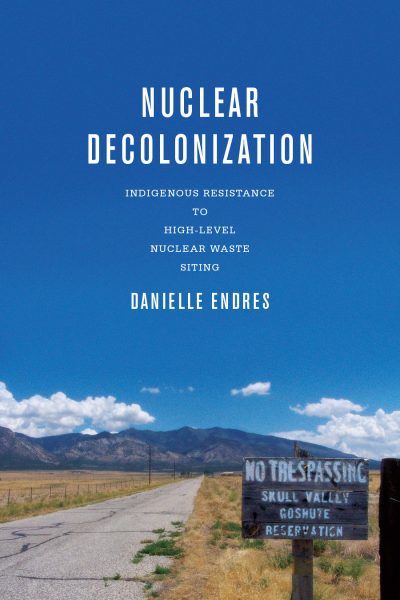

Endres’ book also looks into the plans to store nuclear waste in Goshute’s Skull Valley Land in Utah. The plan was canceled in 2012. Endres notes the Goshute people were divided, with the activists opposing the site and the Tribal Government favoring it due to its economic opportunities.

“That was one of the trickier parts of the book to write and to really honor that even though I didn’t agree with one side, I totally understood why they were arguing for what they were arguing for, and I respect that sovereignty means that’s a decision that they could make,” she said.

Endres also discussed how her book documents what happened on the ground — focusing on the rhetoric about the issue.

“Rhetoric is this window or this lens through which we can really see how language and other simple systems are crucial. They’re not separate from material changes,” she said. “They’re already imbued in material changes.”

One form of rhetoric Endres devoted a lot of time to in her book was “land rhetoric,” which deals with people’s connections and beliefs about the land they inhabit. She also stressed how visiting Indigenous lands helped her gain a stronger appreciation for them.

“I think it’s very common for folks that don’t live in these regions to see those areas as wastelands,” she said. “Why do we want to site nuclear waste in these places? Because they’re perceived as lifeless wasteland sort of places, so I was hoping to nudge my readers … to have a different perspective on these places.”