According to the University of Utah Seismograph Stations, the chance of a 6.75 magnitude or greater earthquake occurring along the Wasatch front in the next 50 years is 43%, while the probability of a 6.0 or greater earthquake is 57%. The UUSS, operating 194 seismic stations, typically detects over 1,500 earthquakes a year in Utah.

The greatest seismic hazard in Utah exists along the 240-mile-long Wasatch fault, capable of producing up to a 7.5 magnitude earthquake. This fault is considered a major geographical risk due to the large number of people concentrated near it. Over 85% of Utah’s population lives within 15 miles of the Wasatch front, according to the earthquake handbook released by the Utah Seismic Safety Commission in 2022.

This population is projected to grow to 2.8 million by 2030 and includes students who live, work and study at the U. The Marriott Library, which contains thousands of occupants at any given time, is located less than one mile from the Wasatch fault.

The USSC says a large earthquake occurs about every 300 years on the five central segments of the Wasatch fault, and the most recent large earthquake took place about 300 years ago on the Nephi segment. The Salt Lake City segment averages 1,300 years between large earthquakes, but the last major one occurred about 1,400 years ago.

This creates expectations for the “big one,” an earthquake with an expected magnitude of around 7.2. This would generate ground shaking “about 32 times more violent” than the 5.7 magnitude earthquake that took place in Magna in 2020, according to the USSC.

So how prepared is the U?

The U follows the International Building Code. The IBC is updated every three years and every state that uses the IBC amends it to local concerns, then publishes it. Utah is currently using the 2021 IBC with Utah amendments, which have been implemented since July 2023.

The U’s Chief Facilities Officer, Robin Burr, said all of the U’s buildings are required to comply with the IBC at the time of their original design and construction, or when major renovations are done. She added there is no requirement to continually update a building as the code changes since this would be disruptive and costly.

“Building codes around earthquake safety have evolved over time, as structural system design technology has evolved, and as more is learned about how buildings respond to different earthquake stresses,” Burr said. “This learning comes from evaluation of building failures after actual earthquake events around the world.”

The USSC says unreinforced masonry buildings, which make up roughly 20% of occupied buildings in Utah, are expected to be responsible for most injuries and deaths in a large earthquake along the Wasatch fault. Utah’s building codes have not allowed this type of construction since 1975, but that doesn’t mean we don’t occupy areas built before then.

Buildings on the U’s campus were built at different times — many of them before 1975, when the building code in Utah started requiring earthquake safety considerations.

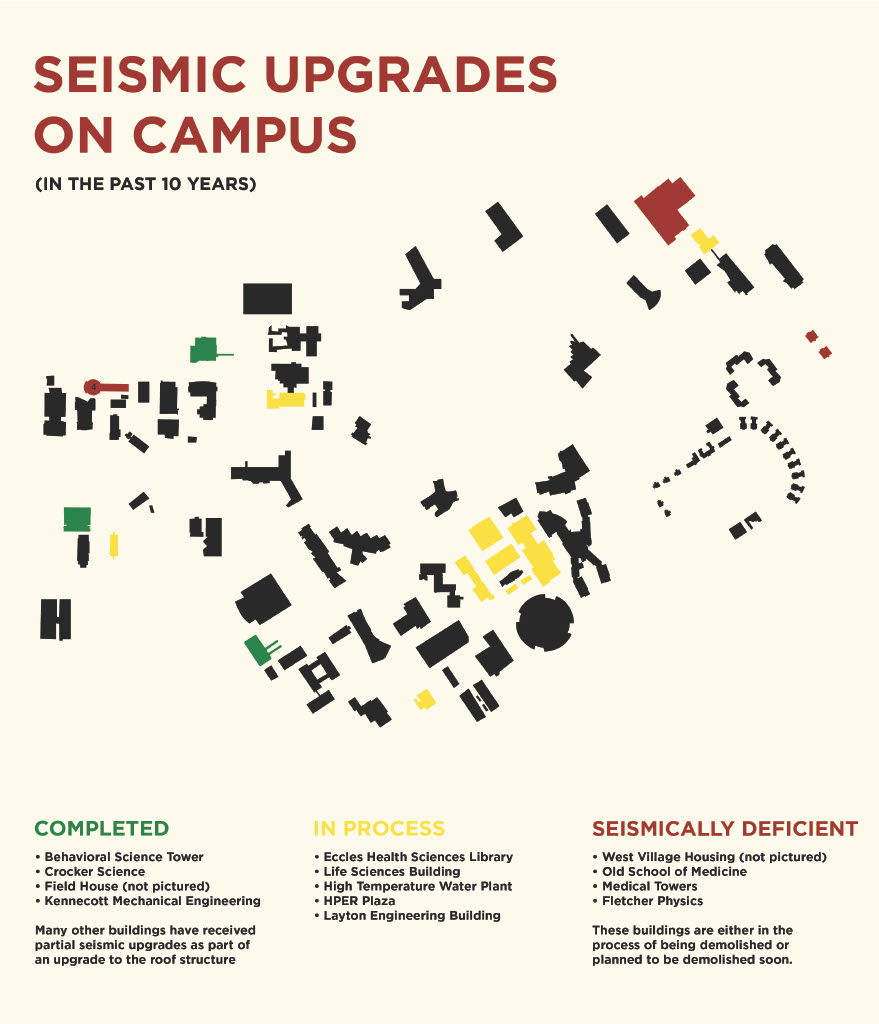

In recent years, there have been renovations done to some of the U’s older buildings to incorporate seismic upgrades. The U’s facilities department provided the Chronicle a list of seismic upgrades completed in the past 10 years, which included the Behavioral Science Tower, Crocker Science Center, Spence Eccles Field House and Kennecott Mechanical Engineering. They added, “many other buildings have received partial seismic upgrades as part of an upgrade to the roof structure.”

“Whenever we do a major renovation, we are required by code to bring the older buildings up to code,” Burr said. “Crocker Science got a major seismic renovation structural upgrade … and Applied Sciences [formerly the William Stewart Building] … we’re also doing a seismic upgrade on it.”

One example of a major building renovation on campus is the Kennecott Building, which was originally built in the 1950s and was renovated by the College of Engineering in 2015. Earthquake stabilization was incorporated into the renovation using shear walls, restrained braces and micropiles, all designed to absorb shock and vibrations from an earthquake.

Another big seismic upgrade on campus was the $45 million renovation to the Marriott Library in 2004, which provided seismic reinforcement to the building, originally built in 1969. This was approved after a 2002 report determined the building would collapse entirely even in the wake of a moderate, magnitude-5 earthquake. The upgrades included shear walls and buckling restrained braced frames, which are the big diagonal braces around the building.

“We do look at where our biggest risk is, and we prioritize and we upgrade,” Burr said.

Burr said any building over 50 years old is considered historic, and an effort is made to preserve the building if possible. This applies to the A. Ray Olpin Student Union, constructed in 1954. Burr said an evaluation was done by a team of engineers and architects to determine if they could renovate the current union building or if it would be better to tear it down completely and rebuild to better suit modern needs. The consensus was that it would be better to tear it down, but Burr said there are no plans in place right now, as it is not yet funded.

Burr said the U maintains a five-year plan including which buildings are in the process of renovations and what buildings are given priority. Buildings currently in the process of renovation include the Eccles Health Sciences Library, the Life Sciences Building, the High Temperature Water Plant, the Health, Promotion, Education and Recreation Plaza, and the Layton Engineering Building.

Buildings with seismic deficiencies that are in the process of being demolished or planned to be demolished soon include the West Village Housing, Old School of Medicine, Medical Towers and Fletcher Physics.

When looking at university safety during an earthquake, another important component is emergency protocols put into place when such events occur.

Emergency Management, a division of the U’s Department of Public Safety, is responsible for the placement of the Emergency Assembly Point program. These points are designated outdoor areas that can be found near all buildings on campus, including the medical school and upper-campus housing.

Stuart Moffatt, the U’s director of Emergency Management, says the U has emergency coordinators in each building that aid in getting people to safety. Coordinators are equipped with radios, have knowledge of their building and are actively working there. They are responsible for observing and finding solutions to keep people safe and helping gather information on the situation.

In an earthquake situation, this information would be received by Moffatt and his team, allowing them to make an informed decision about next steps, for example, whether it would be safe to go back inside buildings or not.

For personal safety, Moffatt recommends remembering the phrase, “drop, cover and hold on.” This means dropping to the ground onto your hands and knees (to avoid being thrown down), covering your head and neck with anything available (a table, a desk, an arm), and holding on to your shelter (or holding on to your head and neck with both arms if you do not have shelter).

Moffatt said although there will always be some damage to buildings after an earthquake, it should be minimal enough to allow people to evacuate and allow renovation in the aftermath.

“There are earthquakes all over the world and we have seen tragic scenes of large buildings that have basically pancaked … our building codes are meant to prevent the pancake,” Moffatt said. “They’re there to hold up the building just enough so that people can evacuate. Then, we have to go through the recovery phase and go back to this building and see how much we need to fix to get back in.”

The impacts of a large earthquake in Salt Lake are predicted to be significant. According to Deseret News, “In 2015, the Utah Chapter of the Earthquake Engineering Research Institute estimated that the ‘big one’ [happening] along the Salt Lake City segment of the [Wasatch] fault would result in approximately 2,500 deaths, 8,000 injuries, 84,000 displaced households, 330,000 households without potable water for over 90 days [and] $33 billion in economic losses.”

Burr said the exact effects of a large earthquake on campus are difficult to predict, as there are so many factors impacting damage that cannot be exactly known.

“It’s not an exact science,” Burr said. “We do not know what the magnitude of the earthquake will be … where the epicenter will be, how long it will go on, and whether it’s shaking up and down or side to side.”

While the epicenter and the time of Utah’s major earthquake are unclear, the U’s Department of Facilities and Emergency Services both work with each other to provide safety measures that will protect students and faculty if an earthquake were to occur.

“University facilities are working very closely with emergency management to make sure we have a plan to respond in the event of an earthquake, and we learned a lot from the one that occurred in March 2020,” Burr said.

Moffatt said it’s normal to have some anxiety about earthquake situations and recommends getting informed as a solution. He encourages students and faculty to check out Utah’s state earthquake website to learn more about how to prepare for an earthquake.

“When I started working here and really diving into the facilities and doing the predictions of damage, I started to walk around campus a little bit nervous that I was in a bad building,” Moffatt said. “It was just so much on my mind and I think that happens normally for people. The way to get over that is to have information.”