Since 2018, around 2,000 community volunteers and over 500 students have taken part in the Wasatch Wildlife Watch project, resulting in 3 million photographs, 17 publications and a better understanding of the conditions of wildlife across the Wasatch Mountains.

“It’s really cool to be a part of something that allows people in the community to actually engage in the conservation of their own local area,” said Gabriel Brown, a senior studying biology who has been volunteering for the project for about two years.

Project lead and University of Utah wildlife biologist Austin Green described the project as a “citizen, science-based camera trafficking project” with the goal of learning about how wildlife throughout the Wasatch Mountains and their ecosystems have responded to nearby urbanization.

“One of the big things that we’re trying to do is understand how populations of animals are either increasing, decreasing or reacting to increases in human influence,” Green said.

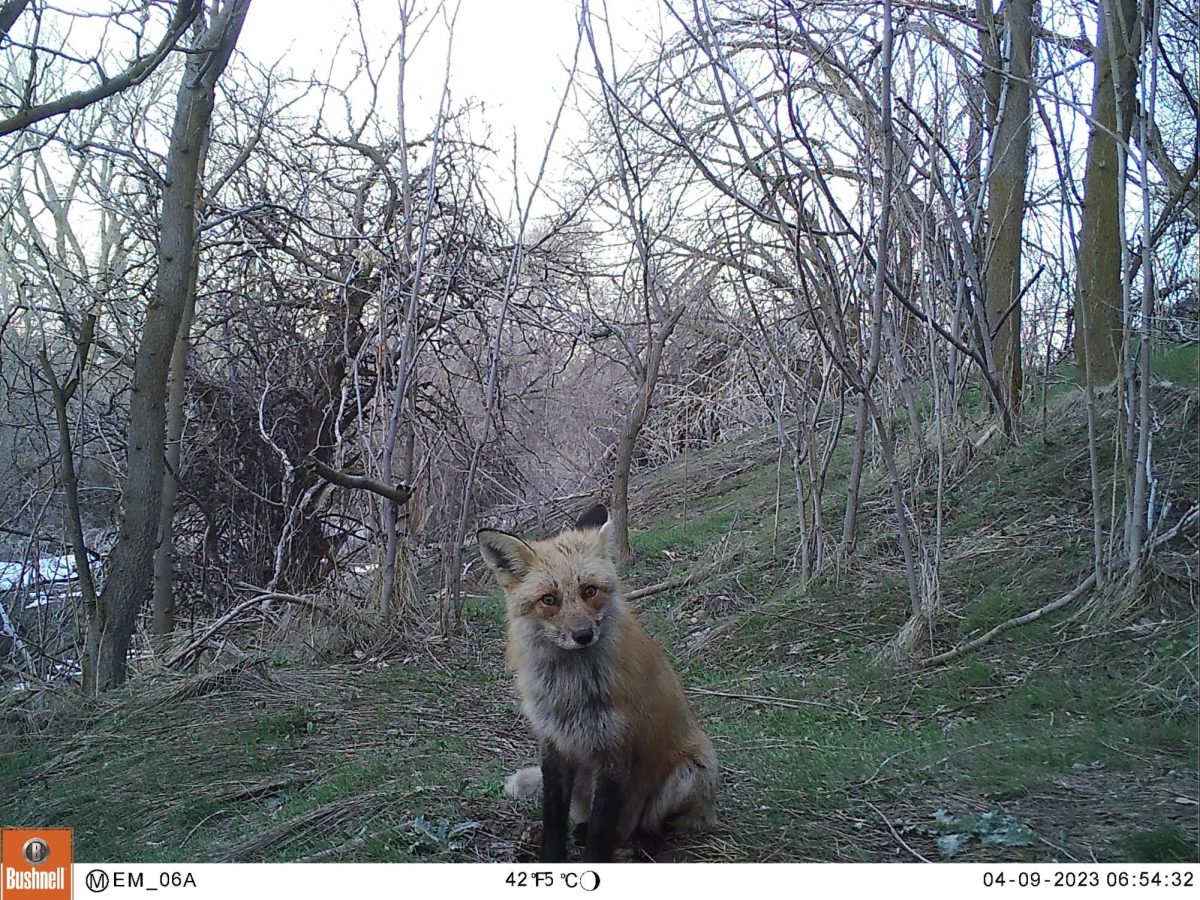

For the project, college and high school students — hundreds of whom have been U students — and community volunteers set up and maintain trail cameras at different sites throughout the Wasatch Mountains that take photos when an animal enters the frame. The creatures trail cameras have snapped pictures of at the sites, of which Green estimates there have been 2,000, include mule deer, domestic dogs, foxes, cougars and moose.

After photos have been taken, students and volunteers look through them, upload them to a database and analyze them to gain more insight into the animals’ patterns of behavior.

Calvin Davidson, a graduated environmental sustainability major who participated in the project last summer, said as someone who’s lived in Salt Lake his whole life, it’s good to know that all different types of wildlife are still thriving, despite human recreation.

“It’s something I’m glad is being done and [it’s] so entertaining to see the animals and critters and everything that’s just been in my backyard my whole life,” Davidson said.

Green said the Wasatch Mountains in Utah are a “pronounced version” of what is called a wildland-urban interface, which refers to any developed piece of land that is butted up against undeveloped land.

“[It’s] one of the best and well known ones in the country,” Green said. “It’s a really nice area to study the effects of humans on wildlife across this gradient of disturbance.”

Green wants to keep this project going as long as possible, because that will only make the data more valuable. He estimated that once they start getting into the 10 and 15 years of monitoring range, they can get an even better idea of population trends in relation to urbanization.

Locally, Green said the most important thing they’ve found are insights into animals’ circadian rhythms, or when they wake up and go to bed, and how this changes in response to urbanization.

He added that the project has also provided preliminary evidence that the wildlife overpass at Parleys Summit, designed to allow animals to cross the busy road, was successful in “alleviating the negative impacts of major habitat fragmentation in a particular area.”

The fact that the project involves so many students and interns, Green said, allows them to garner large-scale observations and trends.

“I think there’s something really powerful about allowing just run-of-the-mill people to be involved in protecting the area around them, and especially here in Utah, where we have so much wilderness area that needs to be protected,” Brown said.

Also, the longer it goes, the more students can get involved with it and take it in their own direction — just like Brown plans to do for a project that will start this summer, where he is studying how different kinds of recreational uses of land in American Fork Canyon impact animal behavior.

“We’re going to be looking at hiking versus camping versus motorized vehicles and comparing those to each other and seeing how are they affecting individual species differently,” Brown said.

However the project grows in the future, volunteers and students will always be at the heart of it. Green said his favorite part of the job is when he stays back from a group of students hiking and listens to them interact with each other, because he thinks that’s where they learn the most.

“I don’t know if the fieldwork is necessarily technically difficult at all — a lot of it’s just hiking and then setting up a small device that anybody could set up, so it’s not like it’s technically difficult, or they’re learning a skill that is absolutely vital to their career progression moving forward,” Green said. “They learn the most when they interact with each other and talk and kind of build that community.”

a.christiansen@dailyutahchronicle.com