What if there was a device that could tell you if the snow was worth skipping class to hit the slopes? Tim Garrett, professor of atmospheric sciences, has created just that.

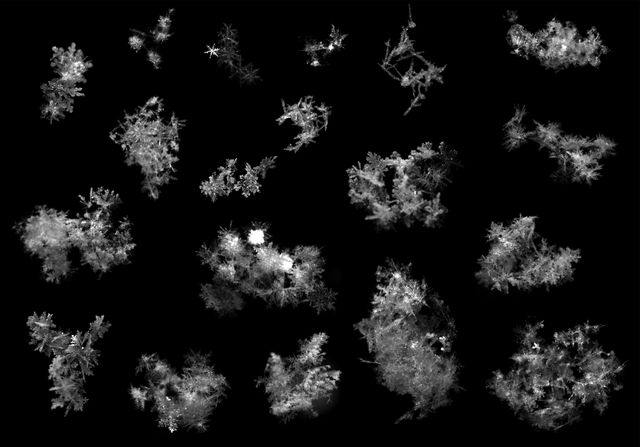

Garrett developed a multi-angle camera that measures and takes photos of falling snowflakes and allows him to predict weather forecasts and snow levels. Garrett’s company, Particle Flux Analytics, currently sells this product around the world. Scientists have so far used it to record snow in Canada, Greenland, the Swiss Alps and Antarctica.

The idea came to him in 2007, when Garrett and a friend were skiing in Washington.

“[The friend] commented that it was interesting how much the snowflake types would vary even from one part of the ski resort to the other part,” Garrett said. “I thought, ‘Wouldn’t this be fun to actually do some real science at the ski resort?’”

When Garrett was hired at the U, that dream became a possibility. Garrett received funding from NASA to buy a snowflake camera from Japan, but it did not work well. He teamed up with engineers at the U to build his own, and after much trial and error, the water-proof camera takes photos from three angles with bright lights (40 Watt LED) and short exposure time (up to 1/40,000th of a second). It’s triggered by sensitive infrared motion sensors that sense snowflakes falling.

Originally, Garrett was driven by his scientific side to further research what little data exists on snowflake shapes.

“It’s not the classic, beautiful snowflake that you would imagine — the classic crystal. But I think it has its own kind of beauty,” he said. “Knowing what snowflakes are shaped like, how big they are and how fast they fall, helps us improve things like weather forecast.”

When forecasts do not match reality, Garrett said it is a lack of understanding about how snowflakes form and fall.

The data can help radar at the Salt Lake City Airport and determine whether or not to delay flights or inform schools when classes should be canceled because of snow on the roads.

Konstantin Shkurko, a PhD student in computer graphics, has worked with Garrett on the snowflake project since 2011, writing the software and fixing computational problems.

Shkurko believes this camera can help tourism industries, both in avalanche warnings and informing skiers of good ski days.

At Alta Ski Resort, the instrument was installed so skiers could access the “Snowflake Showcase” and have access to live-feed of snowflake photos currently on the mountain. The team also developed an app so people could watch falling snowflakes.

Shkurko sees several opportunities to employ this technology.

“I would love to have some kind of consumer version where you can put it in your backyard and plug it in,” Garrett said. “It would work kind of like a weather station.”

Garrett and Shkurko are currently working with engineers from the Center for Engineering Innovation on campus to improve the camera, especially when dealing with harsh, cold weather and wind. As scientists collect measurements of snowflakes around the world, Garrett hopes to see these devices in practical use soon. In the meantime, his skis are in the corner of his office, ready for when the snowflakes make for a good powder day.

c.webber@daiyutahchronicle.com

@carolyn_webber