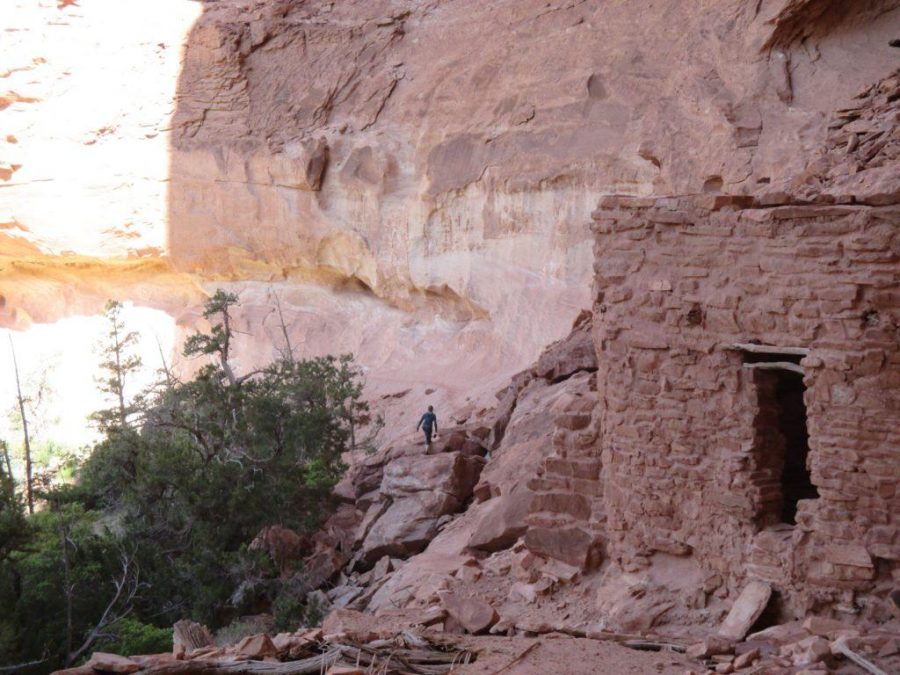

The Bears Ears National Monument proposal is a plea to President Barack Obama to federally protect 1.1 million acres of sacred Native American land in the southeastern corner of Utah.

Twenty-six tribal governments have endorsed the proposal.

United States Secretary of the Interior Sally Jewell and Utah Governor Gary Herbert both agree that there is a need to safeguard these lands. A debate, however, is ensuing about whether the federal government is the right institution to protect the area.

The Hopi, Navajo, Uintah and Ouray Ute, Ute Mountain Ute and Zuni governments submitted the Bears Ears proposal to Obama in October 2015, but the controversy surrounding the monument began in the 1930s.

Outside the U.S. capitol in September, Gov. Herbert told an audience that included Native Americans from San Juan county and members of Utah’s federal delegation, “We don’t want it, we don’t need it.” He argued it would separate tribal members from other Utah residents rather than bring them together.

The majority of tribal members believe the land should be protected and that it’s necessary to do so by process of the president’s signature.

A Salt Lake Tribune-Hinckley Institute of Politics poll shows, however, that residents of Utah are divided over the new national monument — about 43 percent oppose the idea and 40 percent back it. Roughly 17 percent were undecided.

Gavin Noyes, Executive Director of the Utah Diné Bikéyah (UDB), an organization dedicated to protecting ancestral lands of indigenous peoples, supports the designation.

“You have hundreds of people that use the land to maintain cultural traditions,” Noyes said.

Noyes believes that negative opinions of the proposal stem from inaccurate rumors spread by those who oppose the monument.

“It seems safe to assume that any monument designated in response to a proposal by a coalition of 26 tribes will include equally strong protections,” said John Ruple, a law professor at the U’s Stegner Center for Land, Resources and the Environment.

Noyes said that despite what some contend, monument proclamations protect Native Americans’ rights to freely access monuments, to practice their religion within them and to use monument resources such as native plants for cultural purposes.

These rights are also protected by federal laws and agency policies.

“Stakeholders will have an unprecedented voice in how the Bears Ears landscape is managed,” Ruple said.

A national monument designation at Bears Ears would be a pivotal step, Noyes said.

“The enrolled people of the tribes and tribal government should realize that the land once promised to them is continuing to shrink,” said Isaiah Sanchez of the Colorado Ute Tribe.

Between 1877 and 2010, approximately 100 million acres of land that once belonged to indigenous people was lost. If approved, Bears Ears National Monument designation would be the first time in U.S. history that tribal governments are involved in the management of federal public lands, which Noyes says will be a model for other Native American tribes.

Ruple encourages those interested in learning more about the Bears Ears proposal and what it would and would not mean for land management, to read his short paper: National Monuments and National Conservation Areas: A Comparison in Light of the Bears Ears Proposal.

@katie_Buda