Oftentimes sports are played as a distraction from reality. On the court, basketball players can escape and focus on the game, but for some, it’s not that easy. Sometimes through sports, athletes are reminded of the world and what they can’t change, like the color of their skin.

For freshman forward Donnie Tillman and sophomore guard Kolbe Caldwell of the University of Utah men’s basketball team, racial slurs are just as much a part of their lives as a basketball is to the game itself. While the two agree that racial issues aren’t as bad as they once were, they both know they continue to exist.

Life Growing Up

Abandoned houses, gangs and crimes is how Tillman describes home — downtown Detroit, Michigan. According to worldpopulationreview, in 2010, only 13.7 percent of Michigan’s total population was comprised of blacks and African Americans, but they made up 82 percent of Detroit’s total population. Detroit has been ranked among the most dangerous cities, if not the most dangerous city, for years.

“Stat wise, I’m supposed to be dead by now if I stayed there by my 18th birthday,” Tillman said.

Growing up, Tillman said the separation between whites and blacks in Michigan is clear. As a black male, he was told to stay away from white people, especially white girls. In the same breath, he also distanced himself from certain black people. His mom kept him grounded and on the right path by telling him to stay focused, out of trouble and to always be alert. Tillman, who lost eight childhood friends — five to gang-related killings and three to suicides — never forgot what he learned as a kid.

“She knows I’m very trusting and [I] always give people second chances, but she said, ‘Just don’t stay out too late making wrong decisions, you know right from wrong,’” Tillman said. “I took those words to heart.”

Similar to Tillman, Caldwell knew what areas were safe and what spots to avoid in his hometown, at all costs.

“Growing up in Kentucky, there are certain areas where it is dominantly white, and you just don’t go to those areas because they just don’t really associate with us like that,” Caldwell said.

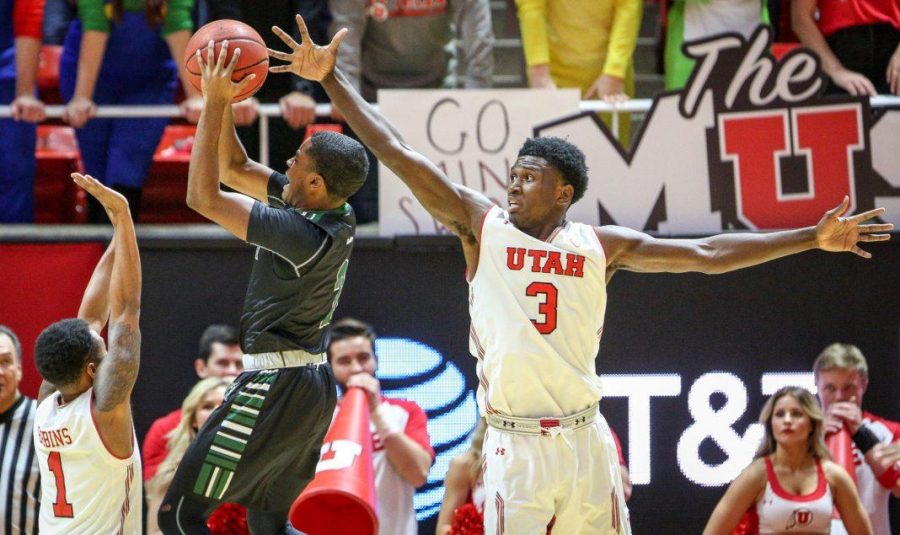

(Photo by Kiffer Creveling | The Daily Utah Chronicle)

Sports Aren’t Exempt from Racism

This invisible line that often divides race and that some people deem okay doesn’t exist solely in towns; Tillman and Caldwell have both felt the boiled blood when they are suited up in game day gear. They admit some high school games were frightening to be a part of because they didn’t know what would take place following the game, whether their team won or lost.

Tillman spent his freshman year of high school in Detroit where he was a part of what’s known as the “East side vs. West side” game.

“That’s always a big deal in Detroit,” Tillman said. “You score something, you can’t be talking because some of those dudes come out with guns, this and that — you’ll get hurt after the game. That’s why you have security walk you to the bus. The police is always there checking pockets. It’s scary, but I’ve always been a quiet kid. I never really say too much to the refs or the crowd; I say it to myself.”

Caldwell also felt uneasy walking to the bus after games because of the uncertainty of what others might do to him, but it’s the name-calling during games he had to learn to ignore. During Caldwell’s freshman year, he was already traveling with the varsity team, and by the time his senior year rolled around, he knew what to expect from the home fans when he and his team were the visiting opponents.

He dealt with the crowd’s comments in high school, and those negative words didn’t disappear when he came to Utah. He said it doesn’t happen as much as it use to, but when the Runnin’ Utes played in-state rival BYU, the crowd reminded him of what he heard on the road in high school.

“It’s rough, but it’s sad, actually. I can’t help the way I am. It’s just the way God made me,” Caldwell said. “When people judge me about that, I just think they’re narrow-minded. I feel bad for them.”

Tillman moved to Las Vegas for his sophomore year where he played basketball at Findlay Prep. He learned then that people would take the time to dig into his life simply to try to bring him down. Against one team in particular, he remembers hearing during that game everything from “You’re not supposed to be here,” to “You’re just another Detroit goon.”

And insults like that have creeped into their everyday lives now.

Finding Ways to Persevere

In January, Tillman was with some of his Utah teammates and they were walking to the car when a pickup truck came flying towards them. Tillman said it looked as if the truck was on a mission to hit them. They got out of the way in time, but not without hearing someone shout the N-word from inside the vehicle.

While Tillman and Caldwell have had to go through things many people will never fully understand without experiencing it themselves, the two know the importance of persevering. Being judged for something they can’t control has influenced how they look at the world.

“With race, I don’t care if you’re white, purple, it doesn’t matter to me,” Caldwell said. “I think everybody should feel the same way.”

b.meservy@dailyutahchronicle.com

@Britt_Meservy