Jacqueline Osherow is a professor in the English department currently teaching a section of ENGL 3030, The Bible as Literature. The class studies all of the books of the Hebrew Bible from a literary perspective rather than a religious approach.

Roots in Text

While growing up in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, Osherow studied the text in Hebrew school, where she found a passion in how you can “open up the text for all kinds of possible readings, some of which contradict each other.” She added, “I remember reading Genesis [in school] and it blew my mind. I was nine. It was in Hebrew, not English, that I was first taught that you could read something two different ways.” From there, her fascination with the text was born. As a part of the Jewish community, Osherow remembers attending a summer camp where only the young boys were taught how to chant, a practice incredibly important to the Jewish faith heavily based on the written word. So Osherow learned on her own. “You would have to go over [the chant] a million times to know it. So, if you are going over it and it’s a great piece of literature, you are going to notice all of these different elements.”

With her roots in the Hebrew literary traditions and her expanding interest in English poetry and its forms, Osherow’s findings began to form interwoven connections of understanding. “Here’s this word that shows up, this echoes that,” Osherow said, “but who was I going to tell it to?” She followed her passion for the study to a Harvard undergraduate program. After traveling abroad and writing poetry, her academic career culminated in receiving her Ph.D. in English and American Literature and Language from Princeton. She moved to Salt Lake to teach creative writing at the University of Utah and continues to be an avid reader and writer. An academic in the best sense of the word, she said, “that’s the point of being a teacher. You get to keep learning.”

Interpretation and Ideas

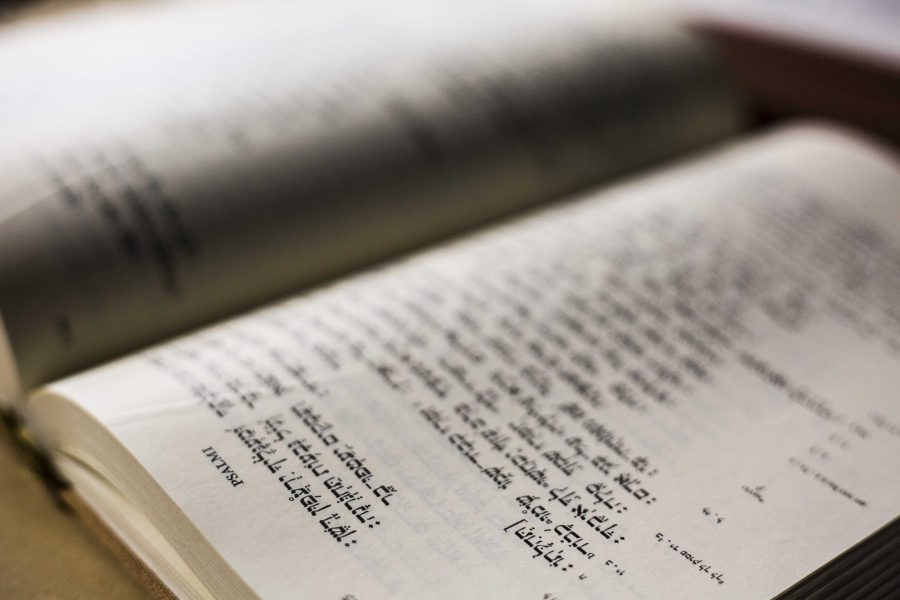

As a new professor teaching an introductory course, Osherow assigned her class the Biblical book that started it all for her — Genesis. As such a famous and influential text, she found that students became more invested in understanding the weight of individual words — why the author used a specific expression, its connotations in the original language and in translations and the implications that it has on the rest of the text. “It’s important [for the students] to realize that they don’t have the original,” Osherow said. Being well-versed in Biblical Hebrew, she hopes her classes understand that so much can be lost in translation of the text. There are hundreds of English versions of the Hebrew Bible, let alone the countless interpretations in other languages. Osherow’s favorite for English study? The King James Version.

(Photo by: Justin Prather | The Daily Utah Chronicle).

Completed in the early 17th century by scholars and members of the Church of England, the King James Version — or King James Bible — is one of the most widely known and utilized translations, despite criticisms of its linguistic style and its mistranslations. Despite the inaccuracies, Osherow posits that the King James Version provides the best translation. “Beauty is a kind of accuracy. And that’s something noteworthy. You can’t translate something beautiful as something ordinary.” That’s what she teaches — exploration out of the ordinary.

Teaching The Class

Osherow’s current ENGL 3030 class is small, comprised of less than 20 students from various educational paths engaging in intimate conversation about the text. Osherow places immense value on having the class discussions be shaped by the individual students and their own lenses of the world, saying, “It matters then that those people are in the room, and not anyone else.” She shies away from monotonously lecturing on the text to allow students to cover the material and enhance their comprehension. “You learn by having to speak. You learn by having to write. My goal is to bring people to make realizations and express themselves, rather than me saying everything.”

While the class has hosted people from many walks of faith, practicing or not, Osherow recognizes that it isn’t for everyone. She knows students who have dropped the class or not taken it, no matter where their faith lies. Some take offense in what secularly approaching they prefer to remain sacred. However, Osherow calls for an open perspective for this in-depth, religion-adjacent study of the text. “Literature is written by people. If you have a problem [with that approach], this might not be the class for you.”

Those currently in her class do come with an open mind, and with surprising interpretations, some that even Osherow herself wouldn’t have identified. She describes this phenomenon in reference to the Bamidbar Rabbah, a holy Jewish text, which says, “There are seventy faces to the Torah: Turn it around and around, for everything is in it.” Approaching the Bible as a piece of literature is continually so captivating because one can find anything and everything in it, discovering new pieces every time you open the book.

It might sound tedious to pick through passages with a fine-toothed comb to find the sliver of meaning. Why doesn’t the text explicitly say what it means? That’s the fun part to Osherow. “I was explaining a reading,” Osherow said, “and somebody raised their hand and asked, ‘Why doesn’t it just say that?’ What I think to be true is that’s the reason it lasts three thousand years. It’s an open text that can be read a lot of different ways. If it just said something it would get out of date. The Bible doesn’t get out of date.”

Religion aside, the Bible still remains a text of supreme importance to history, anthropology, politics, ethics and world culture, and it allows us to examine how it has shaped our world and recognize how we can still interpret its messages.

Poetry and Prose

Osherow’s class also devotes a significant portion of time to the Psalms, which she finds particularly interesting as a poet herself. The Psalms aren’t written in any specific form, but they are driven by an attention to sound as the words would have been sung. They provide a contrast to the more rigid forms of English poetry, such as Shakespeare’s sonnets in iambic pentameter. But the Psalms do provide beautiful parallels and establish internal rhymes that Osherow finds enchanting. They link two traditions that her writings and study follow, both the Hebrew literature and English lyric poems. When asked whether her poetry follows a more rigid structure or more abstract form, Osherow grinned and said, “Whatever works. I’m an opportunist.” More serious, she comes back to the beauty she finds in the text when she said, “The Psalms also use whatever works. They set up expectations and give you an opportunity to break them. It’s magical, without a compromise.”

Osherow’s eighth poetry book “My Lookalike at the Krishna Temple” was released earlier in March, titled so from a story she tells. She explained, “[This man] says to me, ‘There’s a woman who looks just like you in Nepal. She worships with my mother in the Krishna Temple. If you stood next to her, she could be your sister.’ This idea that I had this double across the world … I tried to imagine other religions and wind up saying something new on my relationship to Judaism.” The book, as well as many of her other publications, are available for purchase.

Less poetry is taught now, much to this professor’s chagrin, as the body of prose grows and the requirement for classes that center around poetry’s aspects shrink. But Osherow continues to write poetry from the roots of her religious identity, and advocates for the importance of literature and discussion in our world today. “Any great text is valuable in itself. It’s worthy of attention,” she said. “The more attention you give it, the more it gives back.”

Osherow hopes to continue teaching this class, as well as more capstone or series courses drawing on her favorite Biblical texts. And despite years of study and devotion to the poetry and prose of it all, Osherow paused and smiled again. “I’m still a novice. And I find it infinitely interesting.”

This article is part of the Poynter College Media Project. Click here for more stories and information on the topic “Are U Mormon?”