UMFA Brings Japan to Utah

Kano School (Japanese) The Kiyomizu Temple, Edo period circa 1825, Japanese ink, gouache, paper, wood, silk, gold leaf, 67 in; open: 150 x 3/4 in; closed: 25 1/8 x 4 1/2 in, Purchased with funds from the Mariner S. Eccles Foundation for the Marriner S. Eccles Collection of Masterworks. (Courtesy UMFA)

February 1, 2020

It’s been nearly a decade since the Utah Museum of Fine Arts displayed a full exhibition on the works of Japanese artists. Now, they aren’t just presenting one, but two. With materials drawn from both the UMFA collection and from institutions across the country, the unique but complementary pair of pieces spanning prints, scrolls, armor and more opens on Feb. 6. Curated by Luke Kelly, associate curator at the museum, and Andreas Marks, of the Minneapolis Institute of Art, the two exhibitions are set to bring popular works from several centuries of Japanese art to a contemporary audience. Kelly said, “It is truly a mixture of old and new forms and styles that were in demand.”

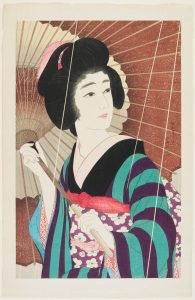

The first of the two exhibits is called “Seven Masters: 20th-Century Japanese Woodblock Prints,” featuring the shin-hanga form as presented by seven prolific artists, with works drawn from the Minneapolis Institute of Art. “Shin Hanga literally means ‘new prints,’” said Luke Kelly. “It was the idea of Japanese dealer Watanabe Shōzaburō. He felt there would be a market for prints done by contemporary artists in the ukiyo-e format, where an artist would work with a woodcarver and printer under the direction of a publisher to bring a print to life.”

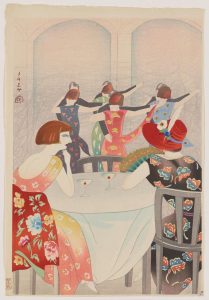

Ukiyo-e prints originated in the 17th century during the Edo period (1603-1868) and were popular throughout Japan for their detailed depiction of kabuki actors, female beauties and gorgeous landscapes. When shin-hanga rose to popularity in the early 20th century, it utilized this division of labor — with many craftsmen working to create one print — that had fallen out of practice in sosaku-hanga art, where one artist completed all of the components themselves. Shin hanga developed, as the museum’s description of the exhibition says, “in response to Japan’s rapid Westernization and industrialization, mingling the old with the new.” As impressionism flourished in the West, as Japanese wood carving reached its peak and as wealth rose to allow art to be a component in middle-class homes — shin-hanga exemplifies the cultural melting pot in 20th century Japan.

The second installation explores the differences between the old and the new in its presentation of the Edo period, aptly titled “Beyond the Divide: Merchant, Artist, Samurai in Edo Japan.” Many of these pieces are drawn from the UMFA’s own collection, featuring beautiful scrolls, screen dividers, sculptures, weapons and the predecessor to shin-hanga prints. “In the Edo period, prints were very popular because they were mass-produced and were inexpensive —for about a bowl of noodles you could get a woodblock print,” said Kelly. The merchant class was rapidly growing in wealth, commissioning art from studios that catered to the upper class of samurai. Print work became not only a status symbol, but a sign of culture as merchants drew on styles from Chinese literati paintings and Western techniques.

In both the Edo period and the masters that came after, these exhibitions display incredible attention to detail of the process — the production of prints alone involved multiple artisans doing meticulous work. “An artist would submit a hanshita, which was a black ink drawing [or] design on which the ley block go the woodblock print would be carved. Depending on the final colors chosen for the print, additional blocks would be carved of the areas that were to be colored.” These exhibitions display an unparalleled cache of pencil drawings and rare proofs that allow patrons an insight into the process.

Yamamura Kōka (Toyonari), Dancing at the New Carlton Café in Shanghai (from an untitled set of ten prints), 1924, woodblock print, ink and color on paper with mica. Published by Yamamura Kōka Hanga Kankōkai. Minneapolis Institute of Art, gift of funds from Ellen Wells, 2014.35. Photo: Minneapolis Institute of Art. (Courtesy UMFA)

Outside of woodblock carvings and prints, “Beyond the Divide” features other art forms, including metallurgy and craftsmanship. “Artisans could explore and recreate older forms of swords and armor to sell. Swordmakers could also travel to find the best materials with which to create their katanas and wakizashis (short sword). Armor makers also created meticulously detailed animal sculptures like the UMFA’s articulated raptor to either give as gifts to elite customers or as a way to advertise their skills,” said Kelly.

With works on display that are new to some of their patrons, Kelly was excited to display both the UMFA’s existing collection and their partnerships with other institutions. “For ‘Beyond the Divide,’ I want visitors to be excited about this wonderful collection that the museum has built over its 69-year existence for the student, faculty and staff of the University, as well as the people of Utah. ‘Seven Masters’ was this opportunity to bring to our visitors a spectacular show from the Minneapolis Institute of Arts, which has one of the best Asian art collection in the United States,” said Kelly.

“Seven Masters” will be on display from Feb. 6 to April 26, and “Beyond the Divide” will be open from Feb. 6 to July 5. Admission is free for U students, staff and faculty.