‘New Perspectives’ on Art’s Role in Stopping Disinformation

April 12, 2020

Art is not just a form of entertainment or a way to escape, it is a weapon that can shape our opinions on politics, cultures and society itself. The media we view informs our perspective and, as new technologies develop, our attention is being controlled in more ways than one. Especially in a world of fake news, art is being used to further the spread of disinformation. But contemporary artists are proving it will be a key component in stopping it.

A New Perspective on Digital Threats

“Disinformation campaigns are more than fake news. They’re coordinated, targeted efforts to shape perceptions. Yet for many, their inner workings remain a mystery.” – The Current No. 001

Jigsaw is a new company within Google designed to predict and plan for digital threats — involving attacks on disinformation, campaigns against censorship and combating harassment and violence online. Recently, they released their first issue of The Current, a publication devoted to examining the links between technology and our society — with its first topic being disinformation.

The most intriguing section is New Perspectives, focused on the role of art in addressing critical issues and how it “enables us to unlock new understandings about the state of the world and build stronger societal resilience.” Jigsaw partnered with Rhizome, an affiliate in residence at the New Museum in New York City highlighting digital art and software development, to commission two contemporary artists to create pieces.

Digital artist Constant Dullaart created “Chorus,” a musical adaptation of a monologue from “The Picture of Dorian Gray,” sung in a monotonous unison against an image of an old computer screen. Its eerie and apathetic nature is designed to remind those who interact with it of the exhaustion of social spread of disinformation.

The other piece is “Baby Faith,” a simple chatbot created by Ryan Kuo as a precursor to his much more inflammatory bot Faith. Where Faith is a caustic and aggressive troll, “Baby Faith” attempts to mirror human emotion in a naive and earnest way, though both bots may become contentious. Kuo writes, “Faith provides no information. She is likely to be trolling you at any time. In place of verbal conflict, Baby Faith makes a nonlinear argument that emerges from typing and reading between the lines. A world can be run, or ruined, on the face value of a feeling.”

Chatting with Baby Faith was one of the most unique online experiences I’ve had. When I purposefully modified my language to that of an internet troll — opinionated and aggressive — the bot shut me down without bias, detecting my emotionally driven language and throwing it back in my face. No matter what spin I took, the bot controlled the conversation and I was at the mercy of its message.

I can objectively understand how the other sections of The Current directly contributed to their mission of strategically fighting the spread of disinformation, but “New Perspectives” spoke on a completely different level. Its artists required such a high level of understanding from me and challenged the way I interact with their work.

Images and Intention through the Lens of Photography

“All photographs are accurate but none are the truth.” – Richard Avedon, photographer

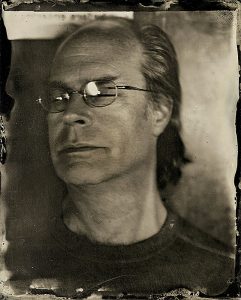

Edward Bateman is the head of the Photography and Digital Imaging area in the Department of Art and Art History at the University of Utah. As an art professor passionate about exploring the relationship between reality and truth with his students, he provided some strong opinions on the nature of art and the duty of artists. “I think that, especially now, artists feel an ethical responsibility to communicate the social values they feel strongly about through their work,” Bateman said. Kuo and Dullaart are no exception — they challenge viewers to connect what they’ve seen to a greater message.

A photographer by trade, Bateman tied this responsibility to the manipulation of images. “What is excluded can often be as important as what is included. A photographer always has an agenda and that influences their creations.” The debate in this lies in interpretation — viewers approaching a piece from different perspectives may disagree on what is metaphorical and what is literal. This is where work is either viewed as art or as propaganda.

As precarious as this sounds, artistic intentions have a major play in how art is absorbed by the public. Bateman acknowledges the difference between photography as an art form and a journalistic tool as an issue of “public trust.” “I do believe that the majority of contemporary artists feel it is their duty to combat information or beliefs that they feel are flat out wrong, inaccurate or dangerous. Art is a culture of critique — it is how students are trained and it created a culture of question,” he said.

In regards to what I discovered through The Current, Bateman gave me a broader grasp of the pieces. Even if I couldn’t quite put my finger on what the works meant, they challenged my perspective on the world and changed the way I approach information now. He said, “Artists, with their understanding of perception and construction of visual meaning, feel especially well-positioned to speak truthfully, to challenge orthodoxies and to change prevailing opinions — even when their message is couched in metaphor.”

Art and The Digital World

“They’re trying to reinforce existing beliefs and get people more entrenched in those beliefs. The more entrenched we are, the less possible it is to agree with the other side.” – Darren Linvill, professor

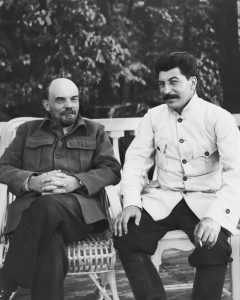

Bateman pointed me toward a Washington Post article by Drew Harwell focused on the effect of doctored images on the public. According to Harwell, even if a faked or altered image is disproven, the audience doesn’t care because their minds have already been made up. Recent examples in politics include a non-existent image of Obama shaking hands with the Iranian president, but date back to photos of Mao Zedong, Vladimir Lenin and Joseph Stalin.

However, recent technology is making fakes harder to detect and making the landscape more precarious. Photoshop is a powerful editing tool and advertisement strategy, but when it fails it’s disconcerting and blatantly wrong. There is a developing technology of “deepfakes” that realistically superimposes facial features, like a more dangerous version of social media filters. Political cartoons have had a long history in American politics, but with the rise of meme culture and social media, parody and relatability are at everyone’s fingertips. The landscape of art and media is constantly shifting, and the responsibility rests on artists to acknowledge their power.

“New Perspectives” is designed to challenge our world view. It’s programmed to be slightly off-putting and make you uncomfortable in the face of technology. We engage with powerful tools every single day and rarely give a second thought to what harmful information we can spread. However, there are artists and developers at work to call out the issues they see and build our resilience as a society to emotionally-charged language, harmful images and falsified information.